9.4: Differentiating Polar Functions

In this section we study the rates of change of polar functions and analyze the slopes of their graphs. Doing so enables us to analyze a polar function's behavior—for example, whether it is approaching or moving away from the origin or an axis. We discuss the following topics:

- Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\)

- Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\)

- Tangents to Polar Curves

Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\)

Consider the function \(r = f(\theta).\) Recall, from Section 9.3, that \(\abs r\) is the distance from a point \((r, \theta)\) to the pole. How do we interpret \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \ques\)

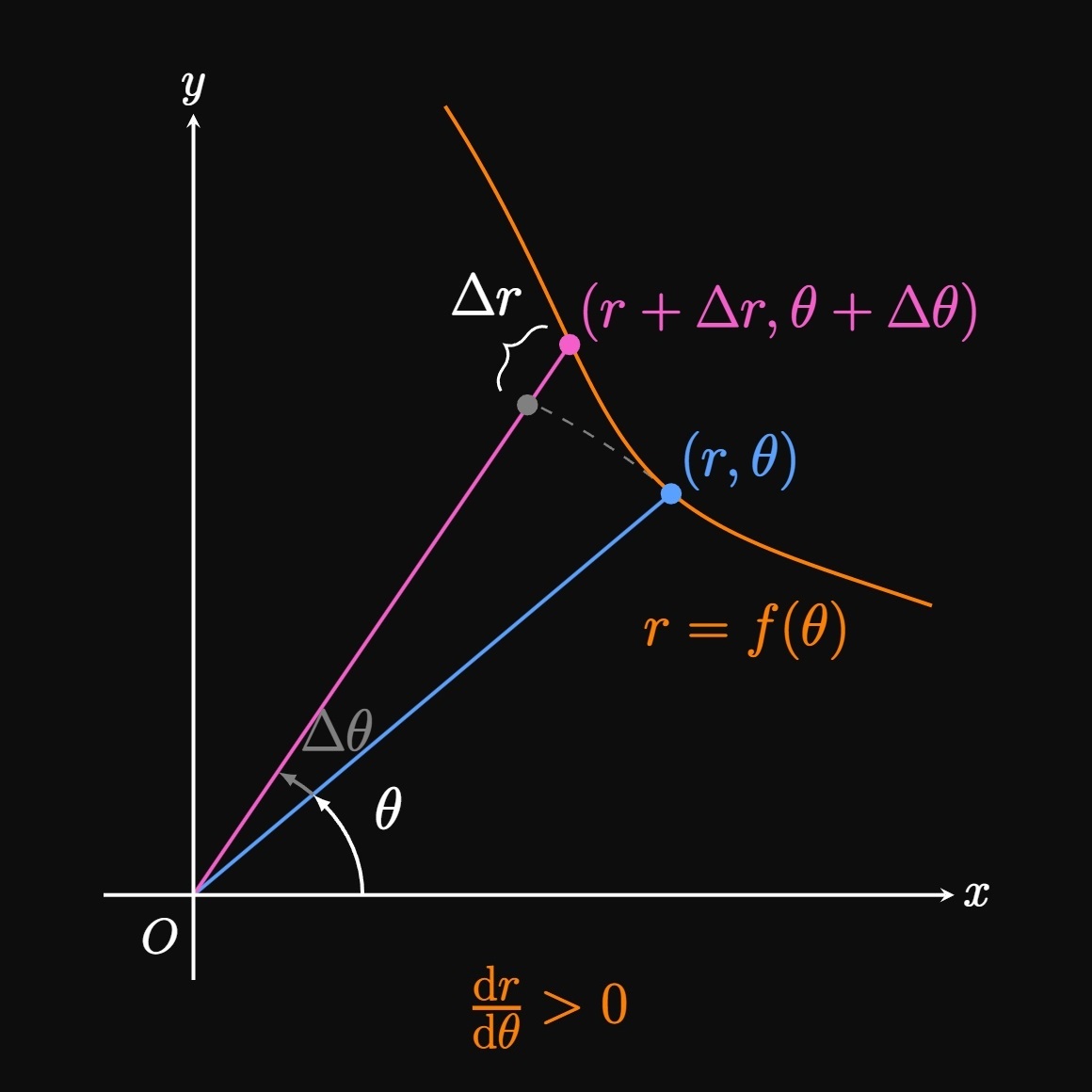

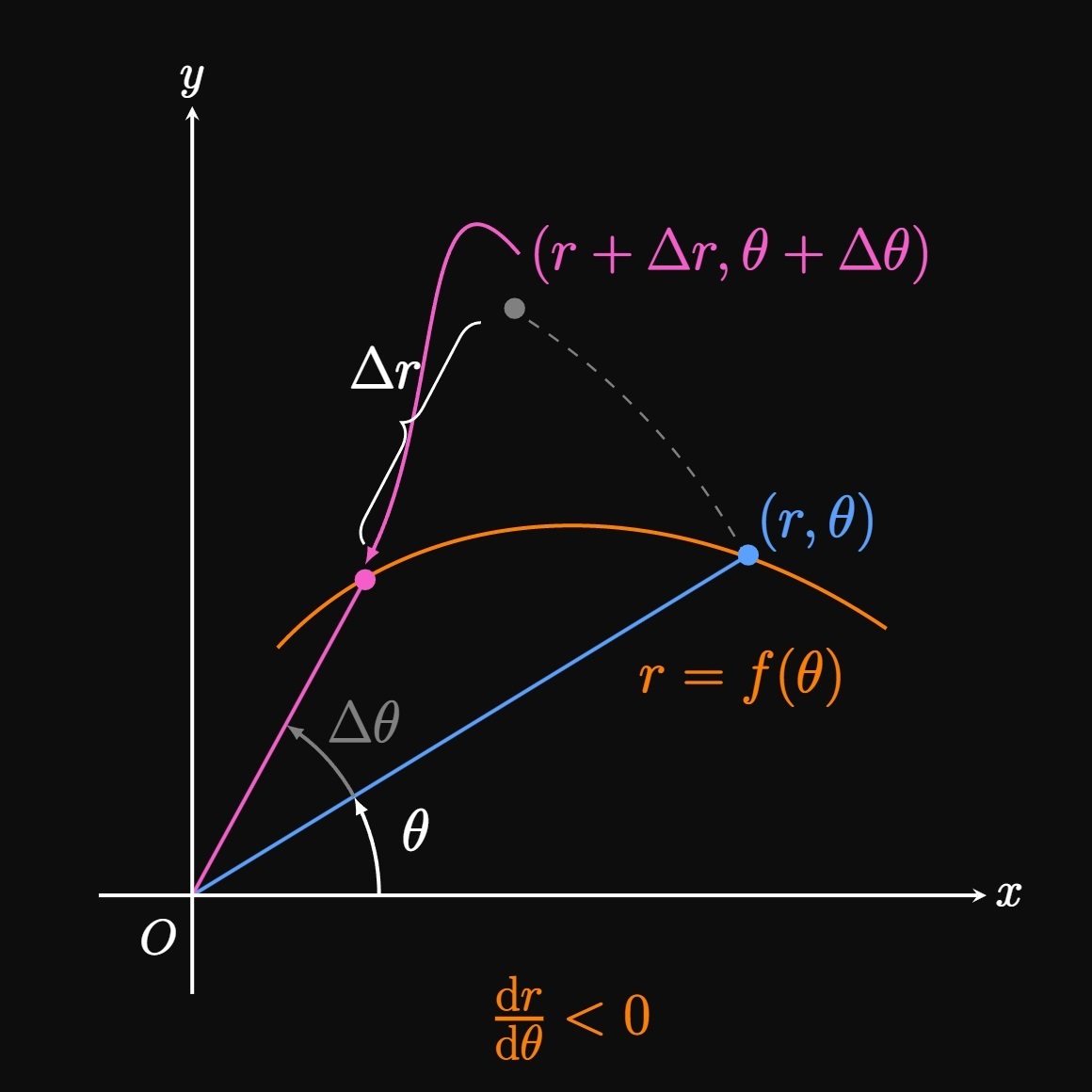

For \(r \gt 0\) If \(r \gt 0,\) then the function \(r = f(\theta)\) gives the distance from the pole to the point \((r, \theta).\) The function \(f\) is increasing if \(f'(\theta) \gt 0\) (or \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \gt 0\)), meaning the distance \(r\) is growing. Hence, as we trace out larger values of \(\theta,\) the points on the graph extend farther from the pole. See Figure 1A: As \(\theta\) is extended, \(\Delta r \gt 0\) because the point \((r + \Delta r, \theta + \Delta \theta)\) is farther from the pole than is the point \((r, \theta).\) Thus, we conclude that, as \(\theta\) increases, points on the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) are moving away from the pole if \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \gt 0\) and \(r \gt 0.\) But if \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \lt 0,\) then this interpretation is flipped: \(r\) is shrinking, so the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) is moving toward the pole. See Figure 1B: When we increase \(\theta,\) we see \(\Delta r \lt 0\) since the point \((r + \Delta r, \theta + \Delta \theta)\) is located closer to the pole than is the point \((r, \theta).\)

For \(r \lt 0\) If \(r\) is negative, then the line segment connecting the pole to \((r, \theta)\) is flipped \(180\degree\) about the pole. Therefore, the distance from the pole to \((r, \theta)\) is the magnitude of \(r.\) If \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \gt 0,\) then \(\abs r\) is decreasing and so the distance is shrinking. Thus, points on the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) are moving toward the pole if \(r \lt 0\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \gt 0.\) But if \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \lt 0\) and \(r \lt 0,\) then \(\abs r\) is increasing and so the distance is extending. So the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) is moving away from the pole if \(r \lt 0\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \lt 0.\)

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(r \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the pole | graph moves toward the pole |

| \(r \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the pole | graph moves away from the pole |

There is an easy way to remember this table:

- If \(r\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) have the same sign, then the graph is moving away from the pole as \(\theta\) increases.

- If \(r\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) have different signs, then the graph is moving toward the pole as \(\theta\) increases.

- \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \intEval_{\theta = \pi/3}\)

- \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \intEval_{\theta = 5\pi/6}\)

- \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \intEval_{\theta = -\pi/4}\)

- We find the derivative to be \[2 \cos \tfrac{\pi}{3} = \boxed 1\] Notice that, when \(\theta = \pi/3,\) \(r \gt 0\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \gt 0;\) each quantity has the same sign. We therefore conclude the following: as \(\theta\) is increased, the graph of \(r = 1 + 2 \sin \theta\) is extending away from the pole when \(\theta = \pi/3.\)

- The derivative is \[2 \cos \tfrac{5\pi}{6} = \boxed{-\sqrt 3}\] When \(\theta = 5 \pi/6,\) we see \(r \gt 0\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} \lt 0;\) these signs are different. Accordingly, as \(\theta\) increases, the graph of \(r = 1 + 2 \sin \theta\) is moving toward the pole when \(\theta = 5 \pi/6.\)

- Our derivative is \[2 \cos \par{-\tfrac{\pi}{4}} = \boxed{\sqrt 2}\] Note that at \(\theta = -\pi/4,\) \(r\) is negative and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) is positive; these quantities have different signs. As \(\theta\) increases, the graph of \(r = 1 + 2 \sin \theta\) is therefore moving toward the pole when \(\theta = - \pi/4.\)

Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\)

From Section 9.3, a polar function \(r = f(\theta)\) can be expressed parametrically as \begin{equation} x = f(\theta) \cos \theta \lspace y = f(\theta) \sin \theta \pd \label{eq:xy} \end{equation} These equations permit us to find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of any point on the graph of \(r = f(\theta).\) If \(f\) is differentiable, then we find \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\) of the polar function using the Product Rule, as follows: \begin{align} \deriv{x}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \cos \theta - f(\theta) \sin \theta \label{eq:dx/dtheta} \nl \deriv{y}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \sin \theta + f(\theta) \cos \theta \pd \label{eq:dy/dtheta} \end{align}

Now the question is how to interpret \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}.\) The key idea is that these are rates at which \(\theta\) causes changes in \(x\) and \(y.\)

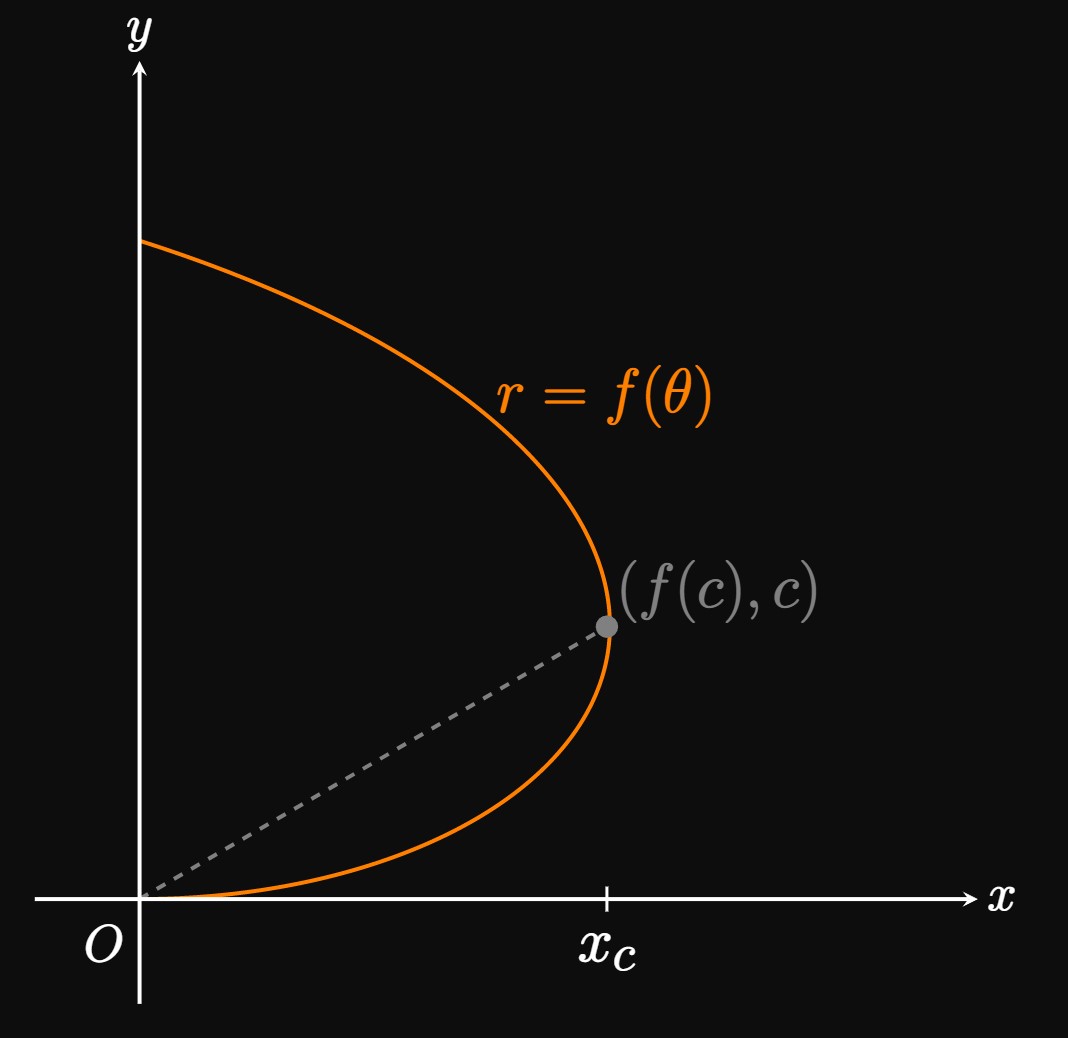

Interpreting \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) If \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \gt 0,\) then the \(x\)-coordinates on the polar graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) are increasing as \(\theta\) grows. If \(x\) is positive, then the graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis. But if \(x \gt 0\) and \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \lt 0,\) then the graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis. For example, see Figure 2: The polar graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) forms a loop in the first quadrant, and the graph has positive \(x.\) For \(\theta\) in \([0, c],\) the \(x\)-coordinates of points on the graph are increasing until they reach \(x_c = f(c) \cos c.\) So for \(0 \lt \theta \lt c\), \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \gt 0\) and so the graph is moving away from the \(y\)-axis. But for \(c \lt \theta \lt \pi/2,\) the graph is contracting toward the \(y\)-axis; thus, \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \lt 0\) over this interval. In addition, the function \(x(\theta) = f(\theta) \cos \theta\) has a relative maximum at \(\theta = c\) by the First-Derivative Test (see Section 3.1) because \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(\theta = c.\)

If \(x \lt 0,\) then the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) is moving away from the \(y\)-axis if \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \lt 0\) and toward the \(y\)-axis if \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \gt 0.\) The graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis if \(x\) and \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) have the same sign. But the graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis if \(x\) and \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) have different signs.

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{x}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{x}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(x \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis | graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis |

| \(x \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis | graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis |

Interpreting \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\) If \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \gt 0,\) then \(y\) increases as \(\theta\) increases. Graphically, the height of the polar graph \(r = f(\theta)\) is rising. For the special case \(y \gt 0,\) the graph is moving away from the \(x\)-axis. If \(y \gt 0\) but \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \lt 0,\) then the graph is moving toward the \(x\)-axis. For example, consider Figure 3: The loop has positive \(y\) for all \(\theta\) in the first quadrant. The graph rises to a maximum height of \(y_c = f(c) \sin c\) before falling back down. So for \(0 \lt \theta \lt c,\) \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \gt 0\) and so the graph is rising, moving away from the \(x\)-axis. For \(c \lt \theta \lt \pi/2,\) \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \lt 0\) and so the graph is approaching the \(x\)-axis. We also identify \(\theta = c\) as the location of a relative maximum of \(y(\theta) = f(\theta) \sin \theta.\)

Now let's suppose \(y \lt 0.\) The graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) is moving away from the \(x\)-axis if \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \lt 0\) and toward the \(x\)-axis if \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \gt 0.\) This pattern is identical to what we've discussed with \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \col\) The graph moves away from the \(x\)-axis if \(y\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\) have the same sign. The graph moves toward the \(x\)-axis if \(y\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\) have different signs.

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{y}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{y}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(y \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the \(x\)-axis | graph moves toward the \(x\)-axis |

| \(y \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the \(x\)-axis | graph moves away from the \(x\)-axis |

Tangents to Polar Curves

The tangent to the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) has slope \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\) To find this value, we regard \(\theta\) as a parameter; in other words, \(\theta\) models our quantities of interest: \(x\) and \(y.\) If \(f\) is differentiable, then \(x\) and \(y\) are differentiable. By the Chain Rule, \[\deriv{y}{\theta} = \deriv{y}{x} \deriv{x}{\theta} \pd\] Dividing both sides by \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) gives \begin{equation} \deriv{y}{x} = \frac{\textderiv{y}{\theta}}{\textderiv{x}{\theta}} \pd \label{eq:dy/dx} \end{equation} This expression enables us to find the slope of \(r = f(\theta)\) at any angle \(\theta.\)

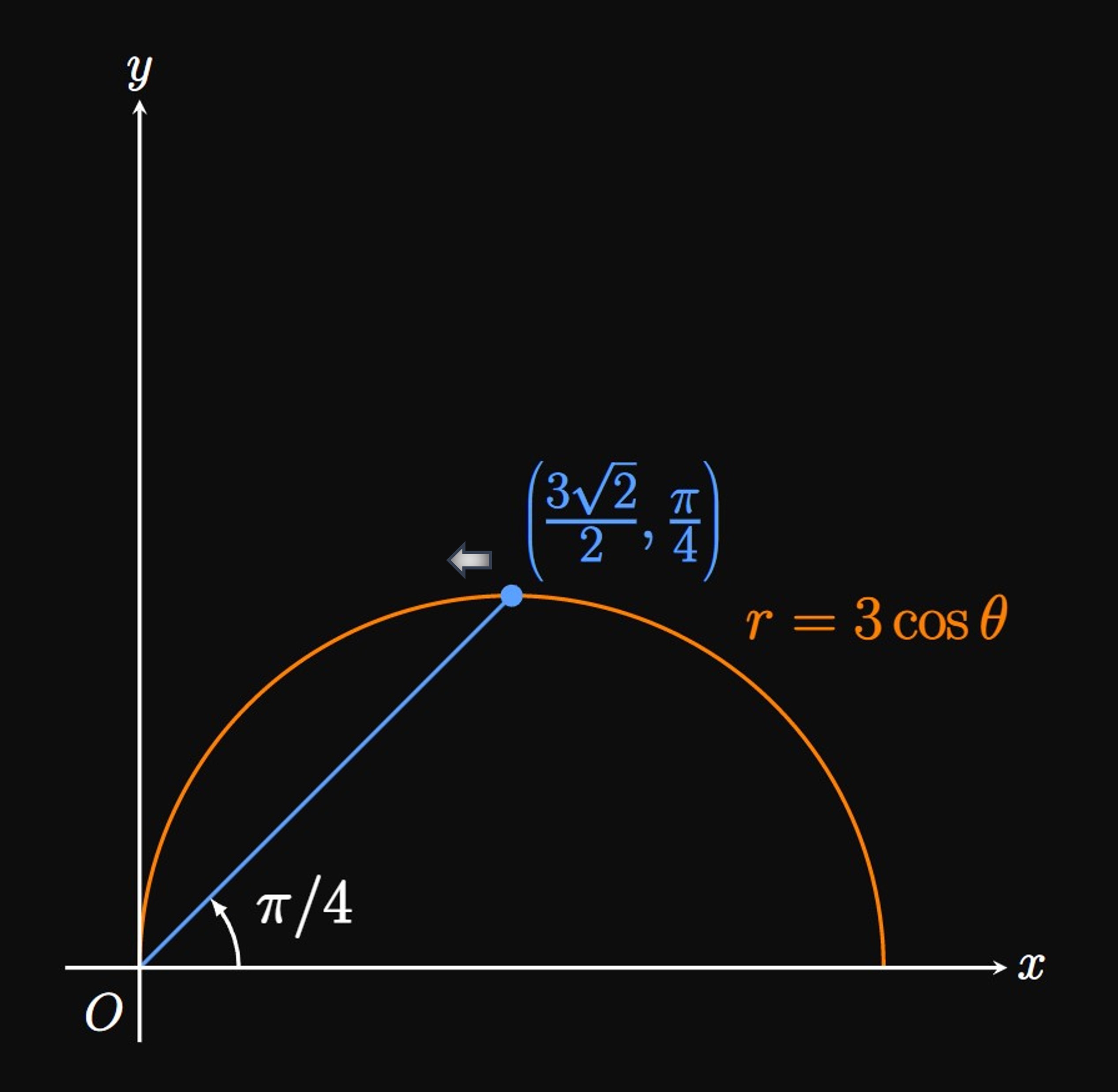

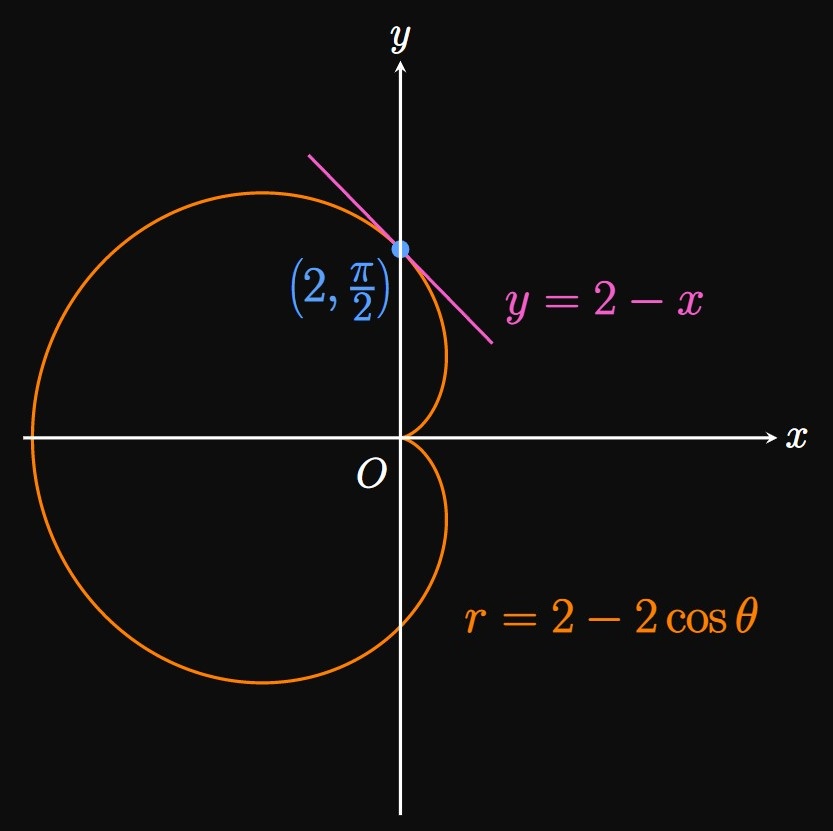

We first need the slope of the curve \(r = 2 - 2 \cos \theta\) at \(\theta = \pi/2.\) \(\eqrefer{eq:dy/dx}\) expresses the slope in terms of \(\theta\) as \[\deriv{y}{x} = \frac{\textderiv{y}{\theta}}{\textderiv{x}{\theta}} \pd\] Thus, we evaluate this ratio at \(\theta = \pi/2.\) From \(\eqref{eq:xy}\) we have \[ \ba x &= (2 - 2 \cos \theta) \cos \theta = 2 \cos \theta - 2 \cos^2 \theta \cma \nl y &= (2 - 2 \cos \theta) \sin \theta = 2 \sin \theta - 2 \sin \theta \cos \theta \pd \ea \] Differentiating each expression with respect to \(\theta,\) we attain \[ \ba \deriv{x}{\theta} &= -2 \sin \theta + 4 \sin \theta \cos \theta \cma \nl \deriv{y}{\theta} &= 2 \cos \theta - 2 \cos^2 \theta + 2 \sin^2 \theta \pd \ea \] So the slope of the curve at \(\theta = \pi/2\) is \[ \ba \deriv{y}{x} \intEval_{\theta = \pi/2} &= \frac{2 \cos \tfrac{\pi}{2} - 2 \cos^2 \tfrac{\pi}{2} + 2 \sin^2 \tfrac{\pi}{2}}{-2 \sin \tfrac{\pi}{2} + 4 \sin \tfrac{\pi}{2} \cos \tfrac{\pi}{2}} \nl &= \frac{2}{-2} = -1 \pd \ea \]

We now construct the equation of the line in point-slope form. When \(\theta = \pi/2,\) \[ \ba x &= 2 \cos \tfrac{\pi}{2} - 2 \cos^2 \tfrac{\pi}{2} = 0 \cma \nl y &= 2 \sin \tfrac{\pi}{2} - 2 \sin \tfrac{\pi}{2} \cos \tfrac{\pi}{2} = 2 \pd \ea \] Hence, the equation of the line is \[y - 2 = -1(x - 0) \or \boxed{y = 2 -x}\] (See Figure 5.)

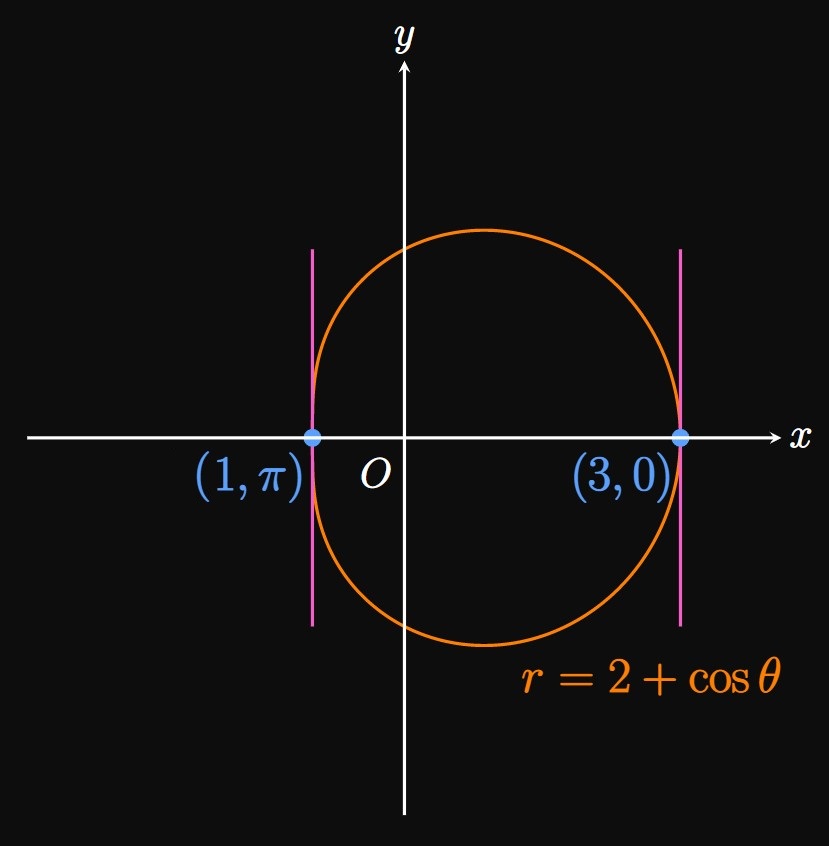

We can use \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) to identify locations of horizontal tangents and vertical tangents. A polar graph has a horizontal tangent at a point if \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} = 0\) but \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \ne 0.\) The graph has a vertical tangent at a point if \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} = 0\) but \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \ne 0.\)

Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) Let \(f\) be a differentiable function, and let \(r = f(\theta)\) define a polar curve. If \(r\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) have the same sign, then the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) is moving away from the pole. Conversely, if \(r\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta}\) have opposite signs, then the graph is moving toward the pole. As \(\theta\) increases, the following table summarizes the behavior of the graph of \(r = f(\theta).\)

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{r}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(r \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the pole | graph moves toward the pole |

| \(r \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the pole | graph moves away from the pole |

Calculating and Interpreting \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}\) If \(f\) is differentiable and \(r = f(\theta)\) defines a polar curve, then \begin{align} \deriv{x}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \cos \theta - f(\theta) \sin \theta \tag*{\(\eqref{eq:dx/dtheta}\)} \nl \deriv{y}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \sin \theta + f(\theta) \cos \theta \pd \tag*{\(\eqref{eq:dy/dtheta}\)} \end{align} As \(\theta\) increases, the following tables summarize the behavior of the graph of \(r = f(\theta)\) for conditions of \(\textderiv{x}{\theta}\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta}.\)

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{x}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{x}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(x \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis | graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis |

| \(x \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the \(y\)-axis | graph moves away from the \(y\)-axis |

| If . . . | \(\ds \deriv{y}{\theta} \gt 0\) | \(\ds \deriv{y}{\theta} \lt 0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(y \gt 0\) | graph moves away from the \(x\)-axis | graph moves toward the \(x\)-axis |

| \(y \lt 0\) | graph moves toward the \(x\)-axis | graph moves away from the \(x\)-axis |

Tangents to Polar Curves If \(f\) is differentiable, then the slope of the polar graph \(r = f(\theta)\) is \[\deriv{y}{x} = \frac{\textderiv{y}{\theta}}{\textderiv{x}{\theta}} \pd \tag*{\(\eqref{eq:dy/dx}\)}\] A polar graph has a horizontal tangent at a point if \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} = 0\) and \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} \ne 0.\) The graph has a vertical tangent at a point if \(\textderiv{x}{\theta} = 0\) and \(\textderiv{y}{\theta} \ne 0.\)