4.1: Antidifferentiation

In Section 2.1 we asserted that a derivative measures a function's rate of change. If we have the rate \(f'(x)\) and want to recover \(f(x),\) then we use antidifferentiation. Antidifferentiation has many applications: If we have a particle's velocity, then we can find its position at a given time. If we know an ecosystem's growth factor, then we can model the population at a given time. In this section we discuss the following topics:

- Defining an Antiderivative

- Evaluating Antiderivatives

- Differential Equations

- Position, Velocity, and Acceleration

Defining an Antiderivative

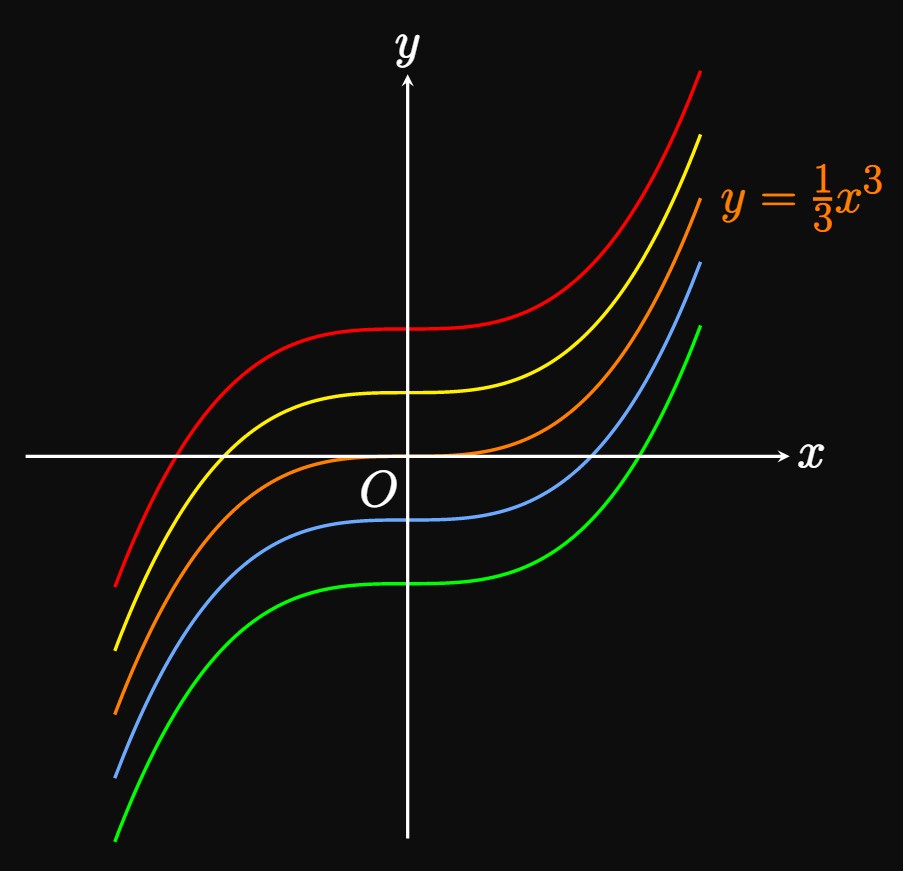

Antidifferentiation is the inverse operation of differentiation: If the function \(g'\) is the derivative of \(g,\) then \(g\) is an antiderivative of \(g'.\) More generally, a function \(F\) is an antiderivative of \(f\) if and only if \(F' = f.\) For example, an antiderivative of \(h(x) = x^2\) is \(H(x) = \frac{1}{3} x^3\) because \(H'(x) = x^2 = h(x).\) But \(H(x) = \frac{1}{3} x^3 + 2\) is also an antiderivative of \(h.\) Therefore, any function \(H(x) = \frac{1}{3} x^3 + C,\) where \(C\) is a constant, is an antiderivative of \(h.\) If a function has an antiderivative, then the function has infinitely many antiderivatives—all of which differ by a constant. Figure 1 shows the graphs of some antiderivatives of \(h(x) = x^2,\) in which all graphs take the form \(y = \frac{1}{3} x^3 + C\) and therefore differ by a vertical translation.

The symbol for the antidifferentiation operator is \(\int \,\)

;

for example, for \(h(x) = x^2,\)

\begin{equation}

H(x) = \int h(x) \di x = \int x^2 \di x = \tfrac{1}{3} x^3 + C \pd \label{eq:int-h(x)}

\end{equation}

The term \(\dd x\) specifies that we antidifferentiate with respect to \(x.\)

Note the following terminology in \(\eqref{eq:int-h(x)} \col\)

-

\(\int \,\)

is the integral sign. - \(h(x) = x^2\) is the integrand.

- \(\dd x\) is the differential.

- \(C\) is the constant of integration.

- \(H(x) = \frac{1}{3}x^3 + C\) is an antiderivative of \(h(x).\)

- The entire expression \(\int h(x) \di x\) is an indefinite integral.

To obtain antidifferentiation statements, we read differentiation statements from right to left. For example, \[ \baat{2} &\deriv{}{x} (\sin x) = \cos x &&\iffArrow \int \cos x \di x = \sin x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} (-\cos x) = \sin x &&\iffArrow \int \sin x \di x = -\cos x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} (\tan x) = \sec^2 x &&\iffArrow \int \sec^2 x \di x = \tan x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} (\sec x) = \sec x \tan x &&\iffArrow \int \sec x \tan x \di x = \sec x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} \par{\sin^{-1} x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} &&\iffArrow \int \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \di x = \sin^{-1} x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} \par{\tan^{-1} x} = \frac{1}{1 + x^2} &&\iffArrow \int \frac{1}{1 + x^2} \di x = \tan^{-1} x + C \nl &\deriv{}{x} \par{e^x} = e^x &&\iffArrow \int e^x \di x = e^x + C \pd \eaat \] The result of each differentiation statement remains unchanged by a constant—for example, \(\textDeriv{}{x} \, (\sin x + C) = \cos x.\) This list drops the constants in the differentiation statements for the sake of familiarity.

- \(\ds \int \cos x \di x\)

- \(\ds \int e^x \di x\)

- \(\ds \int \frac{1}{x} \di x\)

- This problem asks: "The derivative of what function is \(\cos x \ques\)" One such function is \(\sin x.\) But the derivative of \(\sin x\) plus any constant—for example, the derivative of \((\sin x + 1)\) or of \((\sin x - 100)\)—is also \(\cos x.\) Thus, if \(C\) is any constant, then the general antiderivative of \(\cos x\) is \(\sin x + C.\) So \[\int \cos x \di x = \boxed{\sin x + C}\]

- The derivative of \(e^x\) is \(e^x,\) so the converse statement is that \(e^x\) is an antiderivative of \(e^x.\) We always add a constant of integration, so \[\int e^x \di x = \boxed{e^x + C}\]

- Since the derivative of \(\ln|x|\) is \(1/x,\) an antiderivative of \(1/x\) is \(\ln|x|.\) We then add an arbitrary constant in the final answer: \[\int \frac{1}{x} \di x = \boxed{\ln|x| + C}\]

Evaluating Antiderivatives

If \(f(x) = x^n,\) where \(n \ne -1,\) then the Reverse Power Rule gives an antiderivative of \(f\) to be \begin{equation} F(x) = \frac{x^{n + 1}}{n + 1} + C \pd \label{eq:reverse-power-rule} \end{equation} In words, \(\eqref{eq:reverse-power-rule}\) states that to find an antiderivative of a power function (if the power isn't \(-1\)), we add one to the power and divide by the result. This fact is easy to verify because \(F'(x) = x^n = f(x).\) But if \(n = -1,\) then an antiderivative of \(f(x) = x^n\) is \(\ln|x|,\) as we asserted in Example 1.

To evaluate \(\int \dd x,\) we note that \(\int \dd x = \int 1 \di x = \int x^0 \di x.\) Then the Reverse Power Rule gives \[\int x^0 \di x = \int \dd x = \frac{x^{0 + 1}}{0 + 1} + C = x + C \pd\] Since \(\textDeriv{}{x} (x + C) = 1,\) the antiderivative must be correct.

Recall that the derivative of a sum or difference is the sum or difference of derivatives. Thus, an antiderivative of a sum or difference is the sum or difference of antiderivatives. By similar logic, constants can be pulled out of indefinite integrals. The following list shows the properties of antiderivatives, which can be proved by differentiating the results.

- \(\ds \int \frac{1}{x^2} \di x\)

- \(\ds \int \par{5x^4 + \cos x} \di x\)

- \(\ds \int \par{\sqrt{t} - 2 \sin t + \frac{4}{1 + t^2}} \di t\)

- We use the Reverse Power Rule, following \(\eqref{eq:reverse-power-rule},\) to obtain \[\int x^{-2} \di x = \frac{x^{-2 + 1}}{-2 + 1} + C = \boxed{-\frac{1}{x} + C}\]

- We apply a combination of rules, as follows: \[ \baat{2} \int \par{5x^4 + \cos x} \di x &= \int 5x^4 \di x + \int \cos x \di x \comment{\text{by Sum Rule}} \nl &= 5 \int x^4 \di x + \int \cos x \di x \comment{\text{by Constant Multiple Rule}} \nl &= 5 \par{\frac{x^{4 + 1}}{4 + 1}} + \int \cos x \di x \comment{\text{by Reverse Power Rule}} \nl &= \boxed{x^5 + \sin x + C} \eaat \]

- We first write \[ \ba \int \par{\sqrt{t} - 2 \sin t + \frac{4}{1 + t^2}} \di t &= \int \par{t^{1/2} - 2 \sin t + \frac{4}{1 + t^2}} \di t \nl &= \int t^{1/2} \di t - 2 \int \sin t \di t + 4 \int \frac{1}{1 + t^2} \di t \cma \ea \] where the last step is true by the Sum and Difference Rules combined with the Constant Multiple Rule. Using the Reverse Power Rule to antidifferentiate \(t^{1/2}\) then gives \[\frac{t^{3/2}}{3/2} + 2 \cos t + 4 \atan t + C = \boxed{\tfrac{2}{3} t^{3/2} + 2 \cos t + 4 \atan t + C}\]

Differential Equations

An equation that relates \(f\) and its derivatives is called a differential equation. In calculus, we often have a rate \(f'\) and need to find a solution \(f.\) (Differential equations are fundamental to modeling natural phenomena, which we will discuss further in Chapter 8.) To find \(f\) given \(f'\) and an initial condition, we first integrate \(f'.\) Doing so produces a general solution, which contains a constant of integration. But we often want \(f\) to satisfy some initial condition, \(y_0 = f(x_0).\) The combination of a differential equation and an initial condition is called an initial value problem. To solve one, we substitute the given initial condition and solve for the constant of integration, as shown in the following example.

Antidifferentiating \(f'\) gives \begin{equation*} f(x) = e^x + x^2 + 7x + C \cma \end{equation*} which is the general solution to the differential equation. To find the particular solution, we substitute the given initial condition, \(f(0) = 4,\) to obtain \[ \ba f(0) = e^0 + (0)^2 + 7(0) + C &= 4 \nl \implies C &= 3 \pd \ea \] Thus, the particular solution satisfying \(f(0) = 4\) is \begin{equation} f(x) = \boxed{e^x + x^2 + 7x + 3} \pd \label{eq:ex-diff-eq-f(x)-particular} \end{equation}

Verification Checking our answer is simple: It's easy to see that \(\eqref{eq:ex-diff-eq-f(x)-particular}\) satisfies \(f(0) = 4 \col\) \[f(0) = e^0 + 0^2 + 7(0) + 3 \equalsCheck 4 \pd\] Moreover, differentiating \(\eqref{eq:ex-diff-eq-f(x)-particular}\) yields \[f'(x) = e^x + 2x + 7 \cma\] which matches the given differential equation.

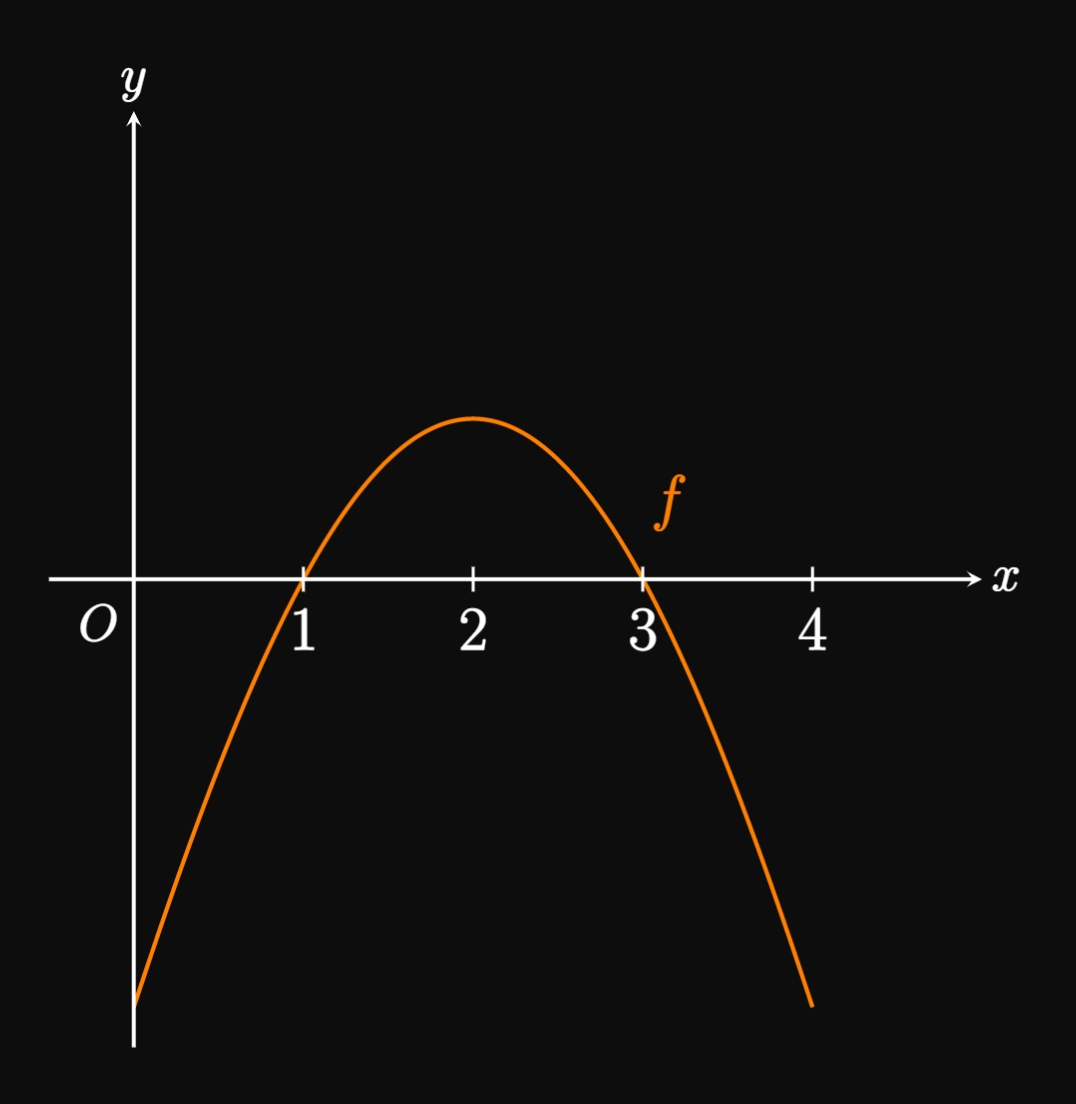

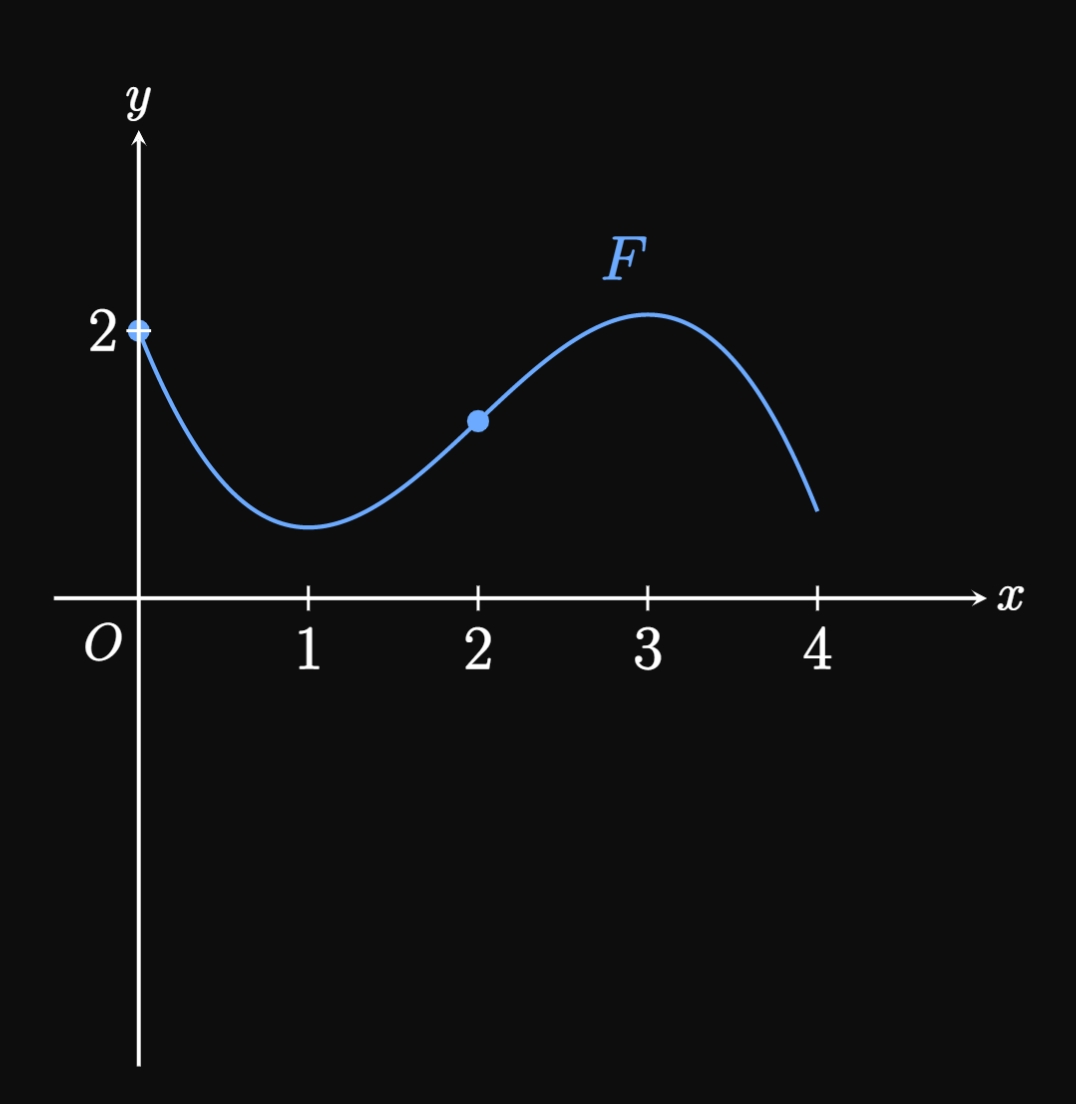

- When \(0 \lt x \lt 1\) and \(x \gt 3,\) \(f\) is negative, meaning the slope of \(F\) is negative. Thus, \(F\) is decreasing on these intervals.

- For \(1 \lt x \lt 3,\) \(f\) is positive, so the slope of \(F\) is positive. Therefore, \(F\) is increasing on this interval.

- Since \(f(1) = 0\) and \(f(3) = 0,\) \(F\) has horizontal tangents when \(x = 1\) and \(x = 3.\) By the First Derivative Test (see Section 3.1), \(F(1)\) is a relative minimum because \(F' = f\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(x = 1.\) Similarly, \(F(3)\) is a relative maximum because \(F' = f\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(x = 3.\)

- For \(0 \lt x \lt 2,\) \(F'' = f' \gt 0\) (since \(f\) is increasing), so \(F\) is concave up on this interval. In contrast, \(F'' = f' \lt 0\) when \(x \gt 2\) (since \(f\) is decreasing), so \(F\) is concave down for \(x \gt 2.\)

- \(F'' = f'\) switches sign at \(2,\) so \(F\) has an inflection point when \(x = 2.\)

Position, Velocity, and Acceleration

In Section 2.1 we connected position to velocity and acceleration using derivatives. These relationships are examples of differential equations. We now relate these quantities using integrals, and we have the tools to solve these differential equations. If \(s(t)\) represents an object's position at time \(t,\) then the particle's velocity function is \(v(t) = \textDeriv{s}{t}.\) Thus, the reverse statement is \begin{equation*} s(t) = \int v(t) \di t \pd \end{equation*} Acceleration, \(a(t),\) is the derivative of velocity, so velocity is the antiderivative of acceleration: \begin{equation*} v(t) = \int a(t) \di t \pd \end{equation*}

Velocity Function Antidifferentiating \(a(t) = 4t + 6\) yields \[ \ba v(t) &= \int (4t + 6) \di t \nl &= 2t^2 + 6t + C \cma \ea \] where \(C\) is a constant. The particle's initial velocity is \(v(0) = 3,\) which we substitute to get \[ \ba v(0) = 2(0)^2 + 6(0) + C &= 3 \nl \implies C &= 3 \pd \ea \] Thus, the velocity function is \[ v(t) = 2t^2 + 6t + 3 \pd \]

Position Function Antidifferentiating the velocity function shows \[ \ba x(t) &= \int \par{2t^2 + 6t + 3} \di t \nl &= \tfrac{2}{3} t^3 + 3t^2 + 3t + D \cma \ea \] where \(D\) is a constant. The initial position is \(x(0) = 2,\) which we substitute to attain \[ \ba x(0) = \tfrac{2}{3}(0)^3 + 3(0)^2 + 3(0) + D &= 2 \nl \implies D &= 2 \pd \ea \] Thus, the position function is \[ x(t) = \boxed{\tfrac{2}{3} t^3 + 3t^2 + 3t + 2} \] One may check this answer by noting that \[\andThree{x''(t) = a(t) \equalsCheck 4t + 6}{x(0) \equalsCheck 2}{x'(0) = v(0) \equalsCheck 3} \pd\]

Objects in Free Fall On Earth's surface, the acceleration due to gravity is \(g,\) whose value is \(32 \undiv{ft}{sec}^2\) or \(9.8 \undiv{m}{sec}^2.\) To analyze an object in free fall, we pick a direction to be positive. For example, it can be convenient to let the upward direction be positive. When an object is thrown upward, its initial velocity is positive because it faces upward, while the acceleration acts downward and is therefore negative.

Since the rock is dropped, its initial velocity is \(v(0) = 0 \undiv{ft}{sec}.\) We take the positive direction to be upward; the rock's velocity and acceleration are therefore both negative as it falls. Also, the object's initial position—its height above the ground, \(h(t)\)—is \(h(0) = 100 \un{ft}.\)

Velocity Function The acceleration due to gravity is a constant \(-32 \undiv{ft}{sec}^2,\) so the velocity function is \[ \ba v(t) &= \int (-32) \di t \nl &= -32t + C \cma \ea \] where \(C\) is a constant. Substituting the initial condition \(v(0) = 0 \undiv{ft}{sec}\) shows \[ \ba v(0) = -32(0) + C &= 0 \nl \implies C &= 0 \pd \ea \] Thus, the rock's velocity function is \[v(t) = -32t \pd\]

Height Function The object's position function (its height above the ground) is given by antidifferentiating \(v(t) \col\) \[ \ba h(t) &= \int (-32 t) \di t \nl &= -16t^2 + D \ea \] for some constant \(D.\) Substituting the initial condition \(h(0) = 100 \un{ft},\) we see \[ \ba h(0) = -16(0)^2 + D &= 100 \nl \implies D &= 100 \pd \ea \] Thus, the height function is \[ h(t) = \boxed{-16t^2 + 100} \]

Immediately Before Impact When the rock reaches the ground, \(h(t) = 0 \un{ft}.\) Solving for the positive value of \(t,\) we have \[ \ba h(t) = -16t^2 + 100 &= 0 \nl \implies t &= 2.5 \un{sec} \pd \ea \] The rock therefore hits the ground after \(2.5 \text{sec}.\) The velocity at this time is \[v(2.5) = -32(2.5) = -80 \undiv{ft}{sec} \pd\] Speed is the magnitude (absolute value) of velocity, so the rock's final speed is \[\abs{v(2.5)} = \abs{-80} = \boxed{80 \undiv{ft}{sec}}\]

- Find the ball's velocity function.

- After how many seconds does the ball reach its maximum height?

- How high does the ball travel?

- If the positive direction is upward, then the ball's initial velocity is \(v(0) = 16 \undiv{ft}{sec},\) and the acceleration due to gravity is \(-32 \undiv{ft}{sec}^2.\) Thus, the velocity function is \[ \ba v(t) &= \int (-32) \di t \nl &= -32 t + C \pd \ea \] Substituting the initial condition \(v(0) = 16 \undiv{ft}{sec}\) gives \[ \ba v(0) = -32(0) + C &= 16 \nl \implies C &= 16 \pd \ea \] Therefore, \[ v(t) = \boxed{-32t + 16} \]

- The ball reaches its maximum height when it is momentarily stationary—that is, when \(v(t) = 0 \undiv{ft}{sec} \col\) \[ \ba -32t + 16 &= 0 \nl \implies t &= \boxed{0.5 \un{sec}} \ea \]

- The position function—the height above the ground, \(h(t)\)—is given by integrating \(v(t) \col\) \[ \ba h(t) &= \int \par{-32t + 16} \di t \nl &= -16t^2 + 16t + D \ea \] for some constant \(D.\) The ball is initially at the ground, so \(h(0) = 0 \un{ft}.\) Substituting this initial condition gives \[ \ba h(0) = -16(0)^2 + 16(0) + D &= 0 \nl \implies D &= 0 \pd \ea \] So the height as a function of time is \[h(t) = -16t^2 + 16t \pd\] The maximum height reached is when \(t = 0.5 \un{sec} \col\) \[h(0.5) = -16 \par{0.5}^2 + 16 (0.5) = \boxed{4 \un{ft}}\]

Defining an Antiderivative

Antidifferentiation is the inverse operation of differentiation.

Function \(F\) is called an antiderivative

of function \(f\) if and only if \(F' = f.\)

We represent an antiderivative by using an indefinite integral:

\[\int f(x) \di x = F(x) + C \cma\]

where \(\int \,\)

is the integral sign,

\(f(x)\) is the integrand,

\(\dd x\) is the differential,

\(F(x)\) is an antiderivative of \(f(x),\)

and \(C\) is the constant of integration.

If a function has an antiderivative, then the function has infinitely many antiderivatives—all of which differ by a constant, \(C.\)

It is easy to verify your answer to an integral: differentiating your answer should return the integrand.

Evaluating Antiderivatives To integrate a power function \(x^n,\) \(n \ne -1,\) we use the Reverse Power Rule: \[\int x^n \di x = \frac{x^{n + 1}}{n + 1} + C \pd \eqlabel{eq:reverse-power-rule}\] But if \(n = -1,\) then \(\int x^{-1} \di x = \ln|x| + C.\) If \(c\) is a constant, \(F\) is an antiderivative of \(f,\) and \(G\) is an antiderivative of \(g,\) then the following properties of antiderivatives are true: \begin{alignat}{3} \int \parbr{f(x) + g(x)} \di x &= F(x) + G(x) + C \cma \comment{\text{Sum Rule}} \eqlabel{eq:int-sum} \nl \int \parbr{f(x) - g(x)} \di x &= F(x) - G(x) + C \cma \comment{\text{Difference Rule}} \eqlabel{eq:int-diff} \nl \int c f(x) \di x &= c F(x) + C \pd \comment{\text{Constant Multiple Rule}} \eqlabel{eq:int-constant} \end{alignat}

Differential Equations A differential equation relates a function \(f\) to its derivatives. To solve a differential equation in which you are given \(f'\) and a specific point (called an initial condition), integrate \(f'\) and plug in the initial condition to solve for the constant of integration \(C.\) A general solution of a differential equation does not have a value for the constant \(C,\) whereas a particular solution does have a value for \(C.\) If you are given an initial condition, then it is possible to find the particular solution.

Position, Velocity, and Acceleration In particle motion, position is related to velocity and acceleration through differential equations. Velocity and acceleration are then connected to position by integrals: If \(t\) is time, \(s(t)\) is position, \(v(t)\) is velocity, and \(a(t)\) is acceleration, then \[v(t) = \int a(t) \di t \and s(t) = \int v(t) \di t \pd\] To solve problems with freefalling objects, select an axis orientation. It is logical to let the upward direction be the positive direction. In these cases a falling object's acceleration is \(-9.8 \undiv{m}{sec}^2,\) or \(-32 \undiv{ft}{sec}^2.\)