0.3: Coordinates and Geometry

Algebra and geometry form the basis for many of the world's designs and physical principles. A calculus student needs a diverse repertoire of techniques for modeling geometric objects, from plotting graphs to calculating distances. In this section we review the following topics:

Coordinates

The \(\bf xy\)-plane is our primary mode of communicating mathematical phenomena with two numbers. It consists of the horizontal \(x\)-axis and the vertical \(y\)-axis, which are perpendicular to each other; the point at which they intersect is the origin, \(O.\) Any point in the plane can be located using a unique set of coordinates, an ordered pair of numbers \((x, y).\) The origin is assigned the coordinates \((0, 0);\) it is our starting point for finding any point in the plane. Figure 1A shows three points—\(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C.\) Beginning at the origin, we locate point \(A (2, 4)\) by stepping \(2\) units to the right and \(4\) units upward. Likewise, we reach point \(B(4, -3)\) by starting at the origin and proceeding \(4\) units to the right and \(3\) units downward. Finally, point \(C\) is reached by traveling \(5\) units to the left and \(1\) unit upward from the origin.

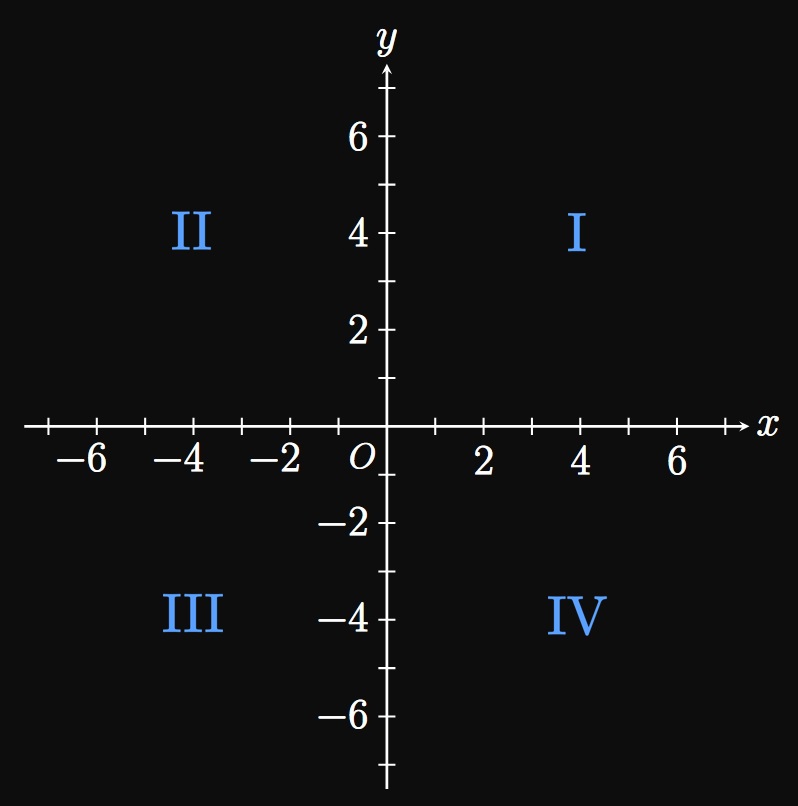

This coordinate system is called the Cartesian coordinate system (or the rectangular coordinate system). We divide the plane into four quadrants—I, II, III, and IV—as shown in Figure 1B. Points in the first quadrant have positive \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates.

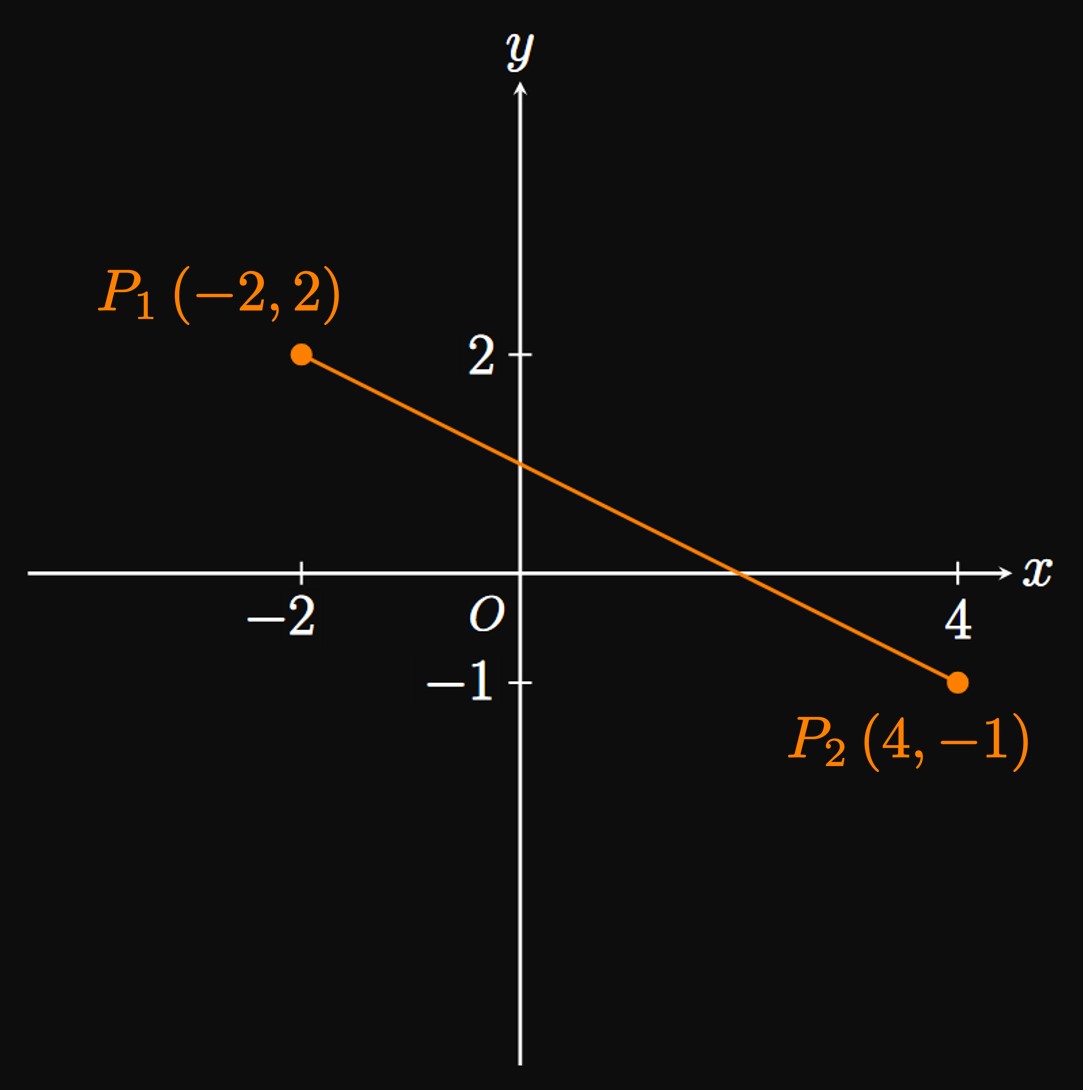

Pythagorean Theorem and Distance Formula Recall that a right triangle has a \(90 \degree\) angle, and its longest side is the hypotenuse, the side opposite the \(90 \degree\) angle. The Pythagorean Theorem relates the hypotenuse's length \(c\) to the lengths of the two other legs \(a\) and \(b\) as follows: \begin{equation} a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \pd \label{eq:pythag-theorem} \end{equation} (See Figure 2A.) The theorem enables us to calculate the distance between two points \(P_1 \par{x_1, y_1}\) and \(P_2 \par{x_2, y_2}\) in the \(xy\)-plane. See Figure 2B: The distance is the length of the line segment \(\length{P_1 P_2}.\) A right triangle is formed by the vertices \(P_1,\) \(P_2,\) and \(P_3;\) the distance between \(P_1\) and \(P_3\) is \[\length{P_1 P_3} = \abs{x_2 - x_1} \pd\] (All distances are absolute values because they can't be negative.) Likewise, the distance between \(P_2\) and \(P_3\) is \[\length{P_2 P_3} = \abs{y_2 - y_1} \pd\] Using the Pythagorean Theorem, as in \(\eqref{eq:pythag-theorem},\) with \(a = \length{P_1 P_3},\) \(b = \length{P_2 P_3},\) and \(c = \length{P_1 P_2}\) yields \[ \abs{P_1 P_2}^2 = \abs{P_1 P_3}^2 + \abs{P_2 P_3}^2 \pd \] Taking the square root of both sides, we attain \begin{align} \abs{P_1 P_2} &= \sqrt{\abs{P_1 P_3}^2 + \abs{P_2 P_3}^2} \nonum \nl &= \sqrt{\abs{x_2 - x_1}^2 + \abs{y_2 - y_1}^2} \nonum \nl &= \sqrt{\par{x_2 - x_1}^2 + \par{y_2 - y_1}^2} \pd \label{eq:dist-formula} \end{align} This equation is the Distance Formula; it is used by maps and navigation systems to compute the distance between two destinations.

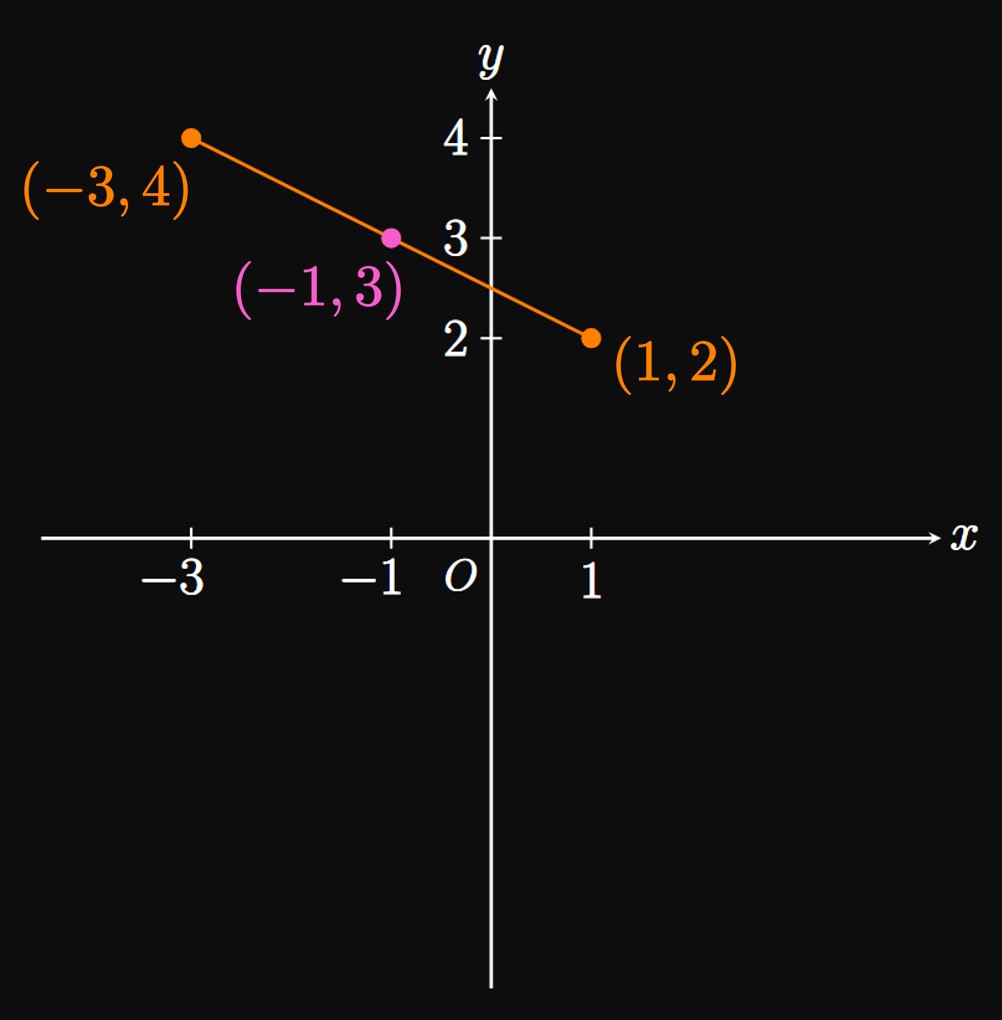

Midpoint The point halfway between the endpoints of a line segment is the midpoint. Mathematically, for two points \(P_1 \par{x_1, y_1}\) and \(P_2 \par{x_2, y_2},\) the midpoint of line segment \(\overline{P_1 P_2}\) is located at \begin{equation} \par{\frac{x_1 + x_2}{2} \cma \frac{y_1 + y_2}{2}} \pd \label{eq:midpt} \end{equation} The midpoint's \(x\)-coordinate is the average of the endpoints' \(x\)-coordinates, and the midpoint's \(y\)-coordinate is the average of the endpoints' \(y\)-coordinates.

Circular Sectors

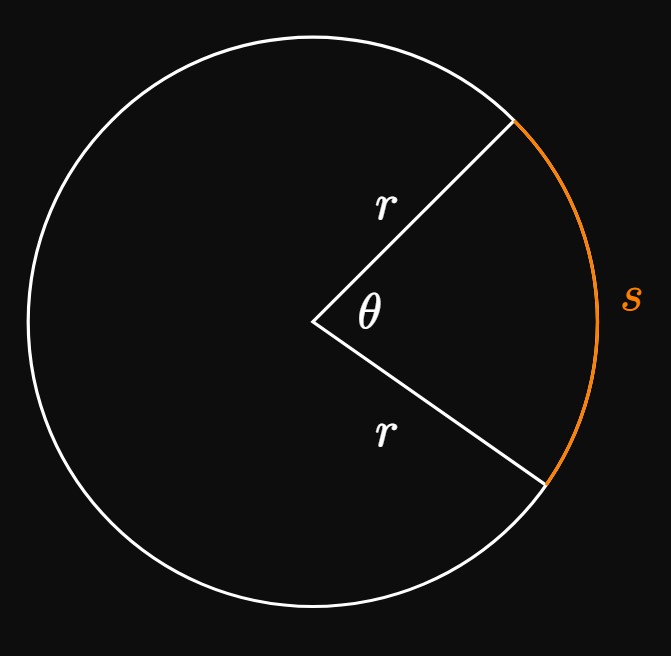

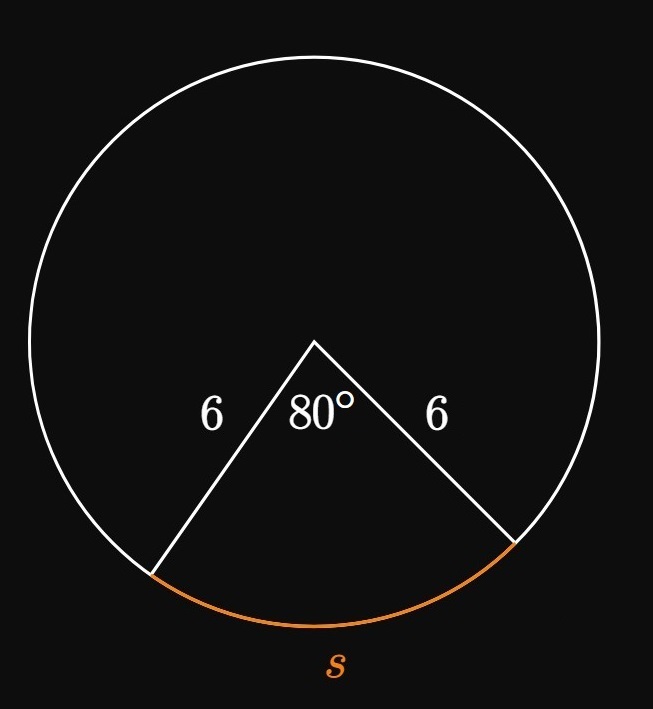

Figure 5 shows a slice cut from a circle of radius \(r;\) this slice is called a circular sector. (Think of a slice of pizza.) The central angle \(\theta\) can be measured in either degrees or radians, a dimensionless unit that represents \(1/(2 \pi)\) of a full circle. A full circle has an angle measure of \(360 \degree,\) so \(2 \pi\) radians is equivalent to \(360 \degree.\) The conversion factor \(\pi \un{rad}\) \(= 180 \degree\) will prove useful as we convert between measures of angles. Suppose that \(\theta\) is measured in radians. The entire circle's circumference is \(2 \pi r,\) so the sector's arc length \(s\) is a proportion \(\theta/2\pi\) of \(2 \pi r\)—namely, \begin{align} s &= \frac{\theta}{2 \pi} \par{2 \pi r} \nonum \nl &= r \, \theta \pd \label{eq:sector-arc} \end{align} Conversely, the entire circle's area is \(\pi r^2,\) so the sector's area is a proportion \(\theta/2\pi\) of this value: \begin{align} A &= \frac{\theta}{2 \pi } \par{\pi r^2} \nonum \nl &= \tfrac{1}{2} \theta \, r^2 \pd \label{eq:sector-area} \end{align} An angle written without the degree prefix \((\degree)\) is implied to be in radians. We prefer to use radians because they lead to the simple, elegant formulas of \(\eqref{eq:sector-arc}\) and \(\eqref{eq:sector-area}.\) And we will soon see that calculus principles rely on angles being given in radians.

- \(\pi/2\) radians to degrees

- \(60 \degree\) to radians

- \(270 \degree\) to radians

- We find \[\frac{\pi}{2} \times \frac{180}{\pi} = \boxed{90 \degree}\]

- We have \[60 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \boxed{\frac{\pi}{3}}\]

- Similarly, we get \[270 \times \frac{\pi}{180} = \boxed{\frac{3 \pi}{2}}\]

Graphs of Circles, Ellipses, and Hyperbolas

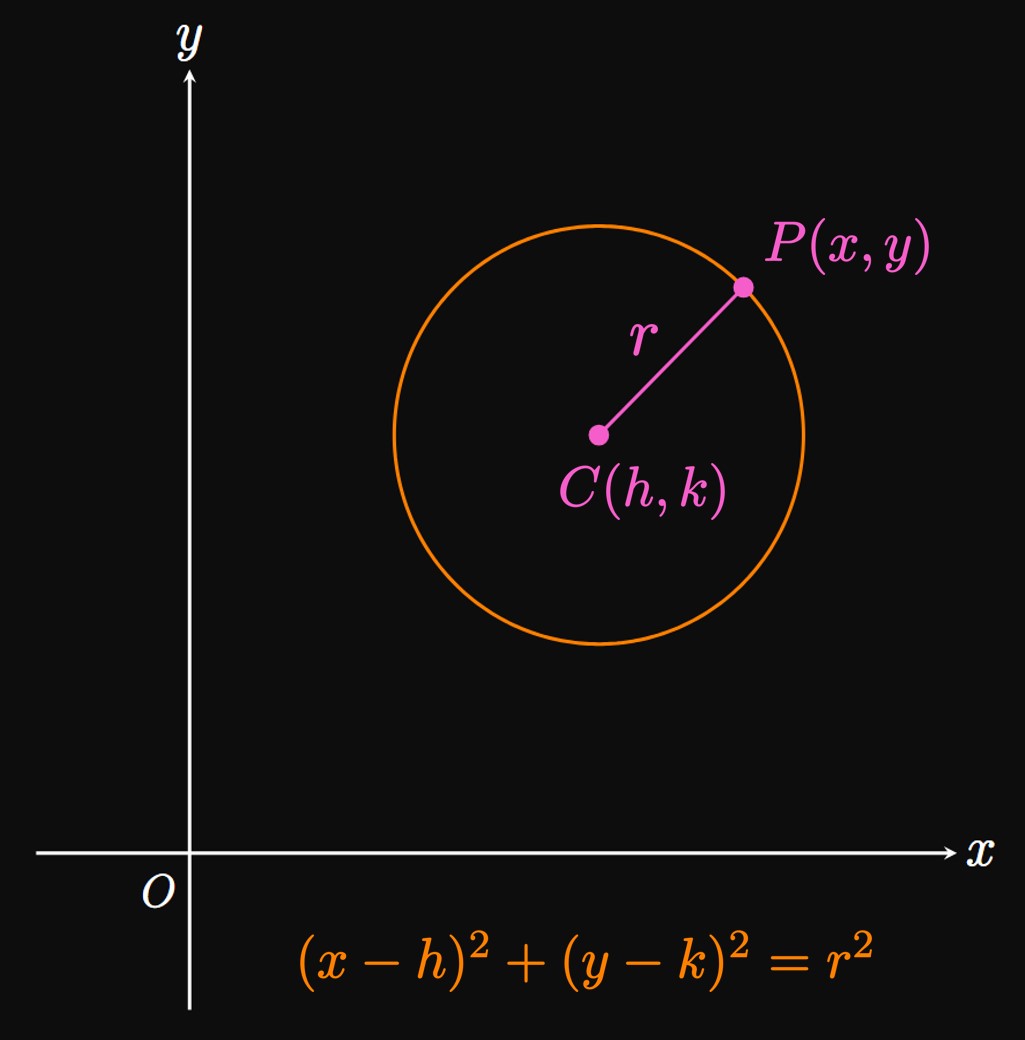

Circles By definition, all points on a circle are equidistant from the center. In the \(xy\)-plane, suppose that point \(C(h, k)\) is the center of a circle of radius \(r.\) Then any point \(P(x, y)\) on the circle must satisfy \(r = \length{PC}.\) So the Distance Formula gives \[ \sqrt{(x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2} = r \pd \] Squaring both sides yields \begin{equation} (x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2 = r^2 \pd \label{eq:circle} \end{equation} This equation produces the graph of a circle of radius \(r\) and center \((h, k).\) (See Figure 7.) If \((h, k)\) \(= (0, 0),\) then the circle is centered at the origin and so \(\eqref{eq:circle}\) becomes \begin{equation} x^2 + y^2 = r^2 \pd \label{eq:circle-O} \end{equation} In calculus, we often use \(\eqref{eq:circle-O}\) due to its symmetry about both coordinate axes.

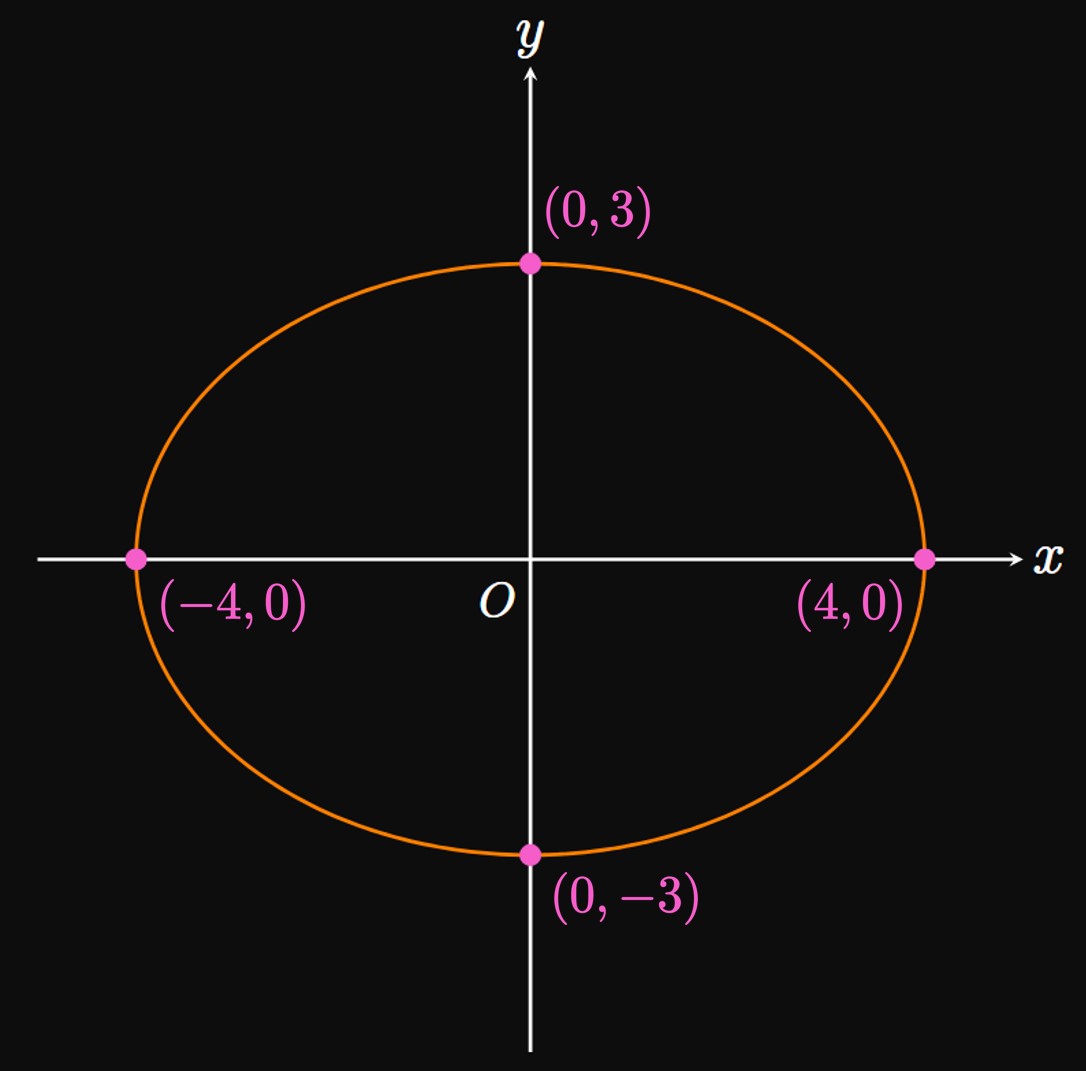

Ellipses A similar shape to the circle is the ellipse, an oval-shaped curve shown in Figure 8. Unlike the circle, not all points on the ellipse are equidistant from the center, \(C(h, k).\) Let \(a\) and \(b\) be positive numbers. From \(C,\) we reach the far-left and far-right points on the ellipse by traveling \(a\) units to the left and right, respectively. Likewise, starting at \(C,\) we reach the top and bottom points on the ellipse by moving \(b\) units upward and downward, respectively. Thus, the ellipse's horizontal length is \(2a\) and its vertical length is \(2b.\) An equation of the ellipse is \begin{equation} \frac{(x - h)^2}{a^2} + \frac{(y - k)^2}{b^2} = 1 \pd \label{eq:ellipse} \end{equation} Similar to the circle, if the ellipse's center is the origin, then \((h, k)\) \(= (0, 0)\) and so \(\eqref{eq:ellipse}\) becomes \begin{equation} \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 \pd \label{eq:ellipse-O} \end{equation}

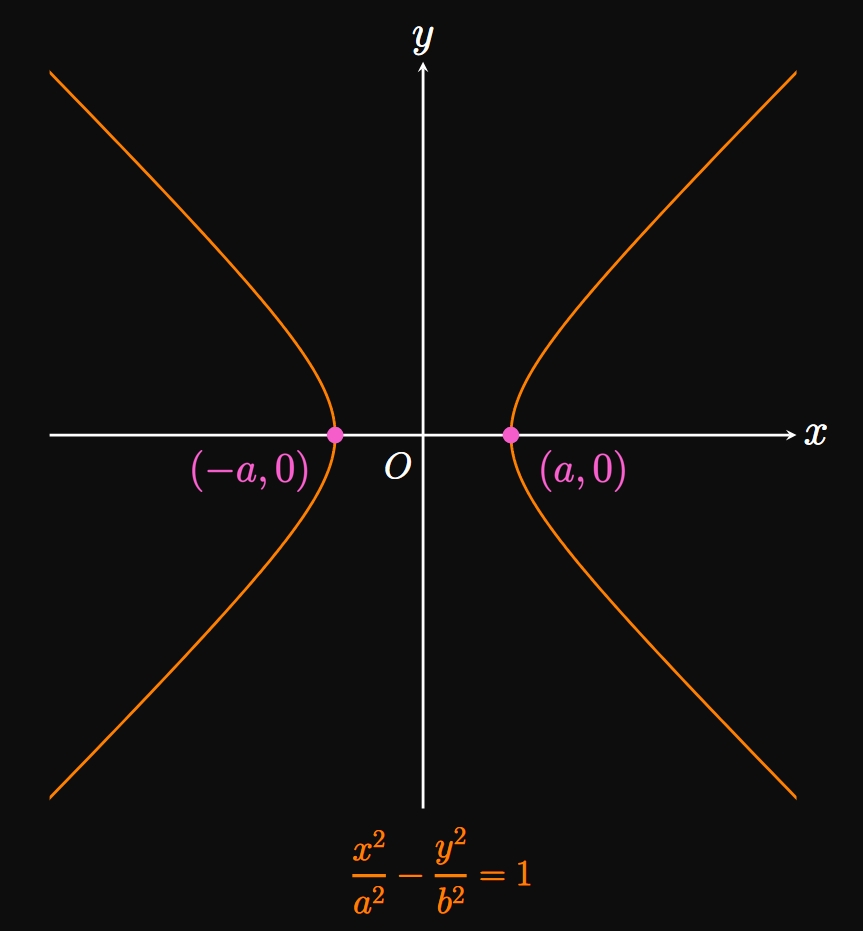

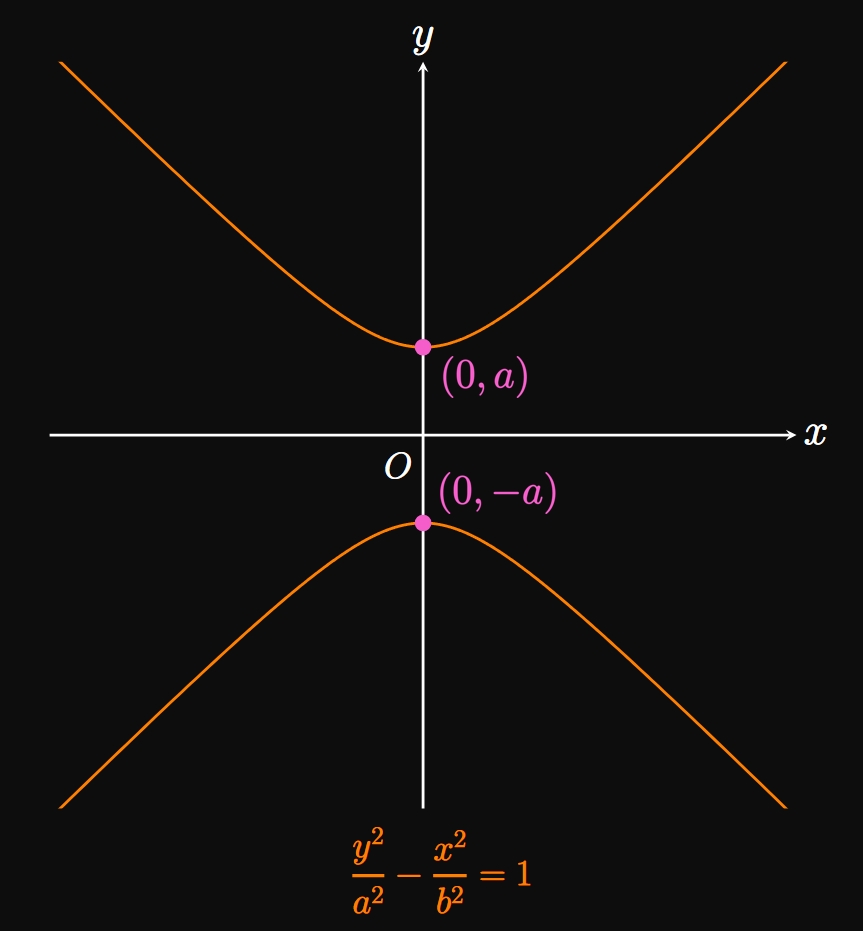

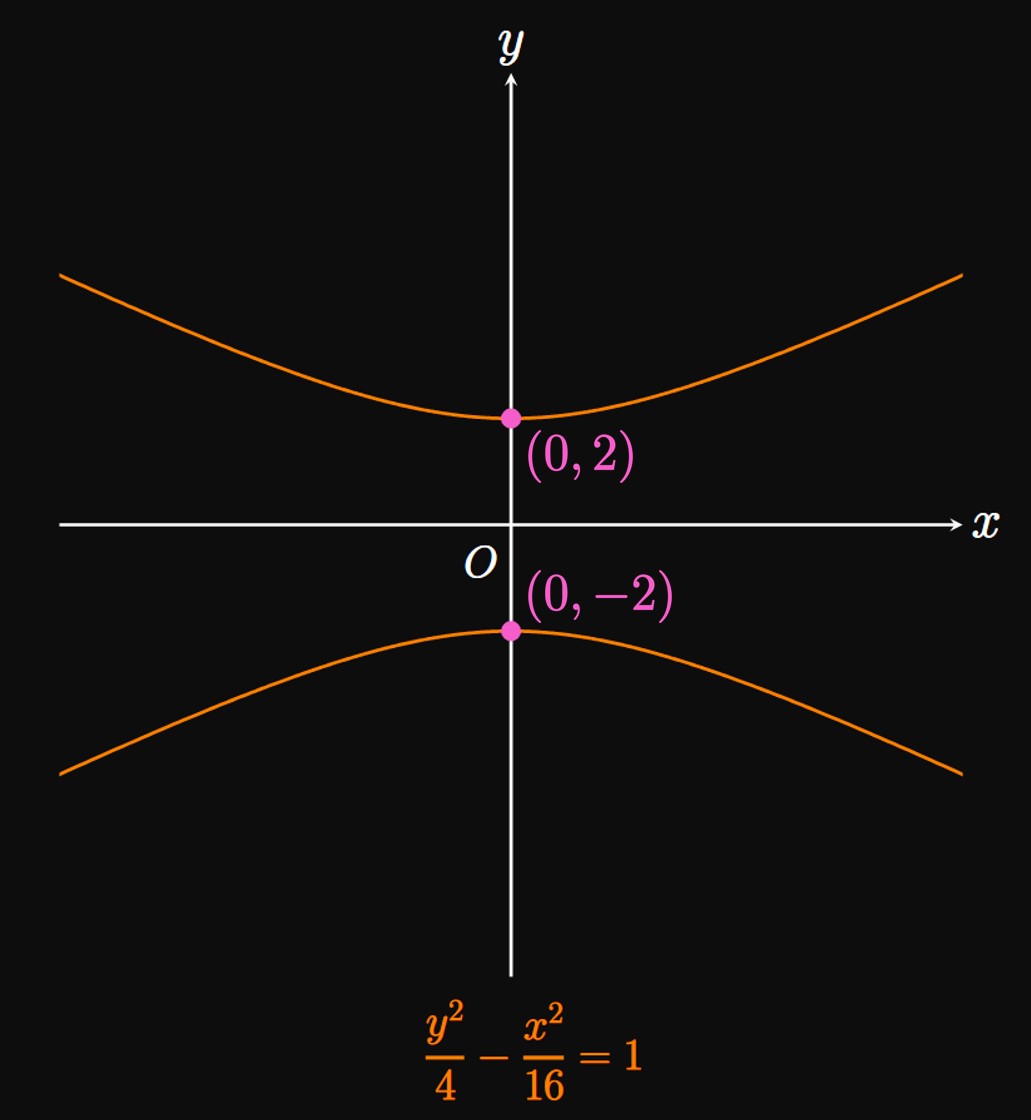

Hyperbolas A hyperbola is an open graph with two branches. Graphing the equation \begin{equation} \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 \label{eq:hyperbola-x} \end{equation} produces a hyperbola whose branches open on the \(x\)-axis, with \(x\)-intercepts at \((-a, 0)\) and \((a, 0).\) (See Figure 10A.) Flipping the roles of \(x\) and \(y\) gives the equation \begin{equation} \frac{y^2}{a^2} - \frac{x^2}{b^2} = 1 \pd \label{eq:hyperbola-y} \end{equation} This graph's branches open on the \(y\)-axis, and it has \(y\)-intercepts at \((0, -a)\) and \((0, a).\) (See Figure 10B.) The value of \(b\) scales the hyperbola; later in this text, we will elaborate on its role as we build our calculus toolkit.

Coordinates We use the \(\bf xy\)-plane to represent combinations of two numbers. Any point in the plane can be located using a unique set of coordinates, an ordered pair of numbers \((x, y).\) The plane consists of the horizontal \(x\)-axis and the vertical \(y\)-axis, which are perpendicular to each other. The origin is the point \(O(0, 0)\) at which both coordinate axes intersect. It is our starting location for locating any point in the plane. This system is called the Cartesian coordinate system (or the rectangular coordinate system). The first quadrant has coordinates whose \(x\)- and \(y\)-values are positive. A right triangle's longest side is the hypotenuse, located across from the \(90 \degree\) angle. The Pythagorean Theorem relates the hypotenuse length \(c\) to the lengths of the two other legs \(a\) and \(b,\) namely, \begin{equation} a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \pd \eqlabel{eq:pythag-theorem} \end{equation} By the Distance Formula, the distance between two points \(P_1 \par{x_1, y_1}\) and \(P_2 \par{x_2, y_2}\) is \begin{equation} \abs{P_1 P_2} = \sqrt{\par{x_2 - x_1}^2 + \par{y_2 - y_1}^2} \pd \eqlabel{eq:dist-formula} \end{equation} The point halfway between the endpoints of a line segment is the midpoint. A line segment whose endpoints are \(P_1 \par{x_1, y_1}\) and \(P_2 \par{x_2, y_2}\) has a midpoint of \begin{equation} \par{\frac{x_1 + x_2}{2} \cma \frac{y_1 + y_2}{2}} \pd \eqlabel{eq:midpt} \end{equation}

Circular Sectors A radian is a dimensionless measure of an angle. There are \(180 \degree\) in \(\pi\) radians. To convert from degrees to radians, we multiply by \(\pi/180;\) to convert from radians to degrees, we multiply by \(180/\pi.\) A circular sector is a slice of an entire circle, analogous to a slice of pizza. If a circular sector has radius \(r\) and central angle \(\theta,\) measured in radians, then its arc length and area are, respectively, \begin{align} s &= r \, \theta \cma \eqlabel{eq:sector-arc} \nl A &= \tfrac{1}{2} \theta \, r^2 \pd \eqlabel{eq:sector-area} \end{align}

Graphs of Circles, Ellipses, and Hyperbolas A circle is a shape whose points are all equidistant from the center. Plotting the following equation gives a circle of radius \(r\) and center \((h, k) \col\) \begin{equation} (x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2 = r^2 \pd \eqlabel{eq:circle} \end{equation} If the circle is centered at the origin, then its equation is \begin{equation} x^2 + y^2 = r^2 \pd \eqlabel{eq:circle-O} \end{equation} An ellipse is an oval-shaped curve. If an ellipse's width is \(2a\) and its height is \(2b,\) and its center is \((h, k),\) then its equation is \begin{equation} \frac{(x - h)^2}{a^2} + \frac{(y - k)^2}{b^2} = 1 \pd \eqlabel{eq:ellipse} \end{equation} If the ellipse is centered at the origin, then its equation is \begin{equation} \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 \pd \eqlabel{eq:ellipse-O} \end{equation} A hyperbola is an open curve that has two branches. The equation \begin{equation} \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 \eqlabel{eq:hyperbola-x} \end{equation} produces a hyperbola that opens horizontally and has \(x\)-intercepts of \((-a, 0)\) and \((a, 0).\) Conversely, the equation \begin{equation} \frac{y^2}{a^2} - \frac{x^2}{b^2} = 1 \eqlabel{eq:hyperbola-y} \end{equation} yields a hyperbola that opens vertically and has \(y\)-intercepts of \((0, -a)\) and \((0, a).\)