5.4: Shell Method

In Section 5.3 we introduced the Disk Method and Washer Method, which enable us to calculate volumes of solids of revolution. We learned the following facts:

- The Disk Method is used when there is no gap between a region and the axis of revolution.

- The Washer Method is used when there is a gap between a region and the axis of revolution.

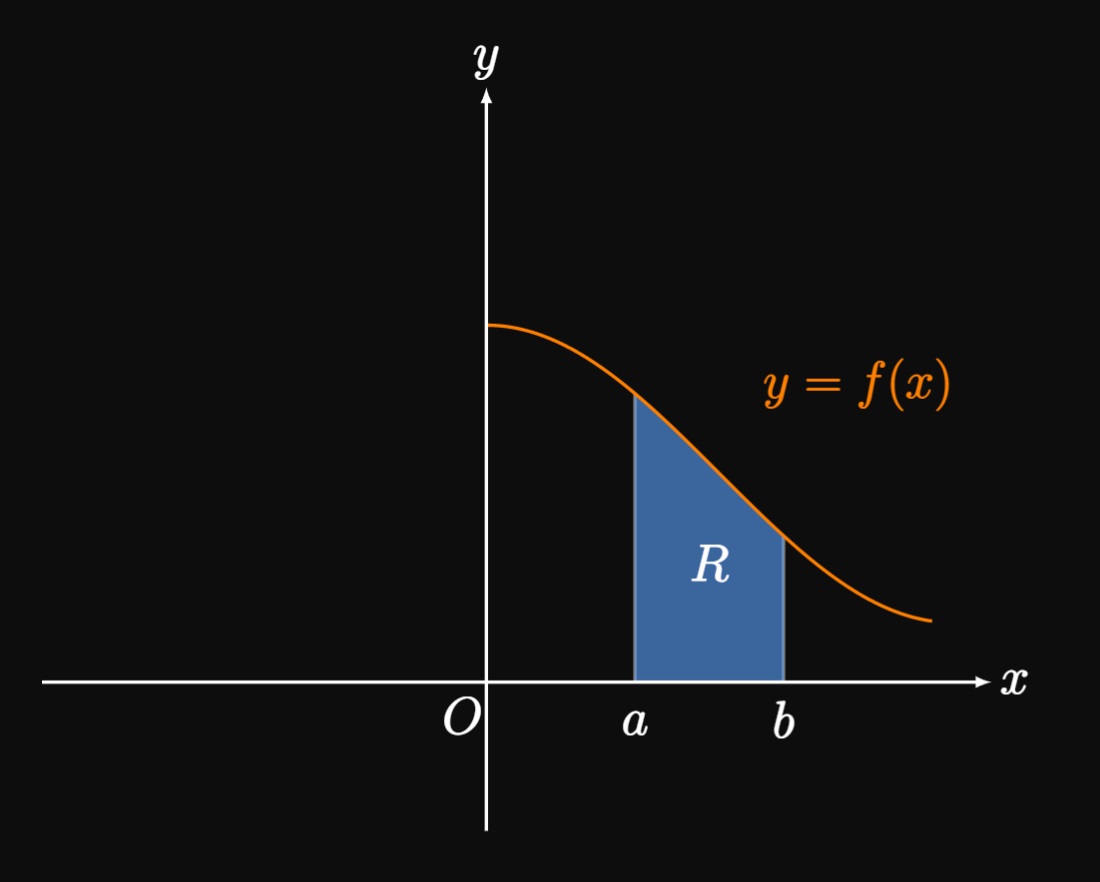

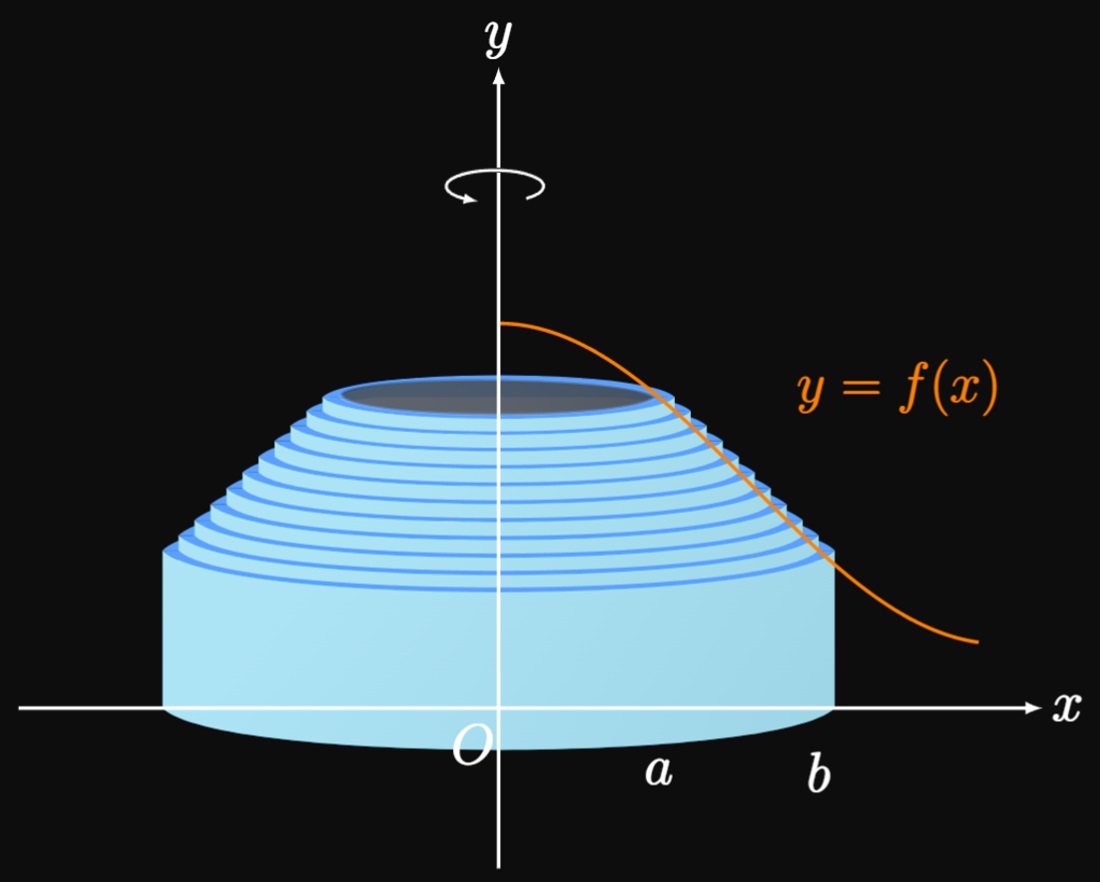

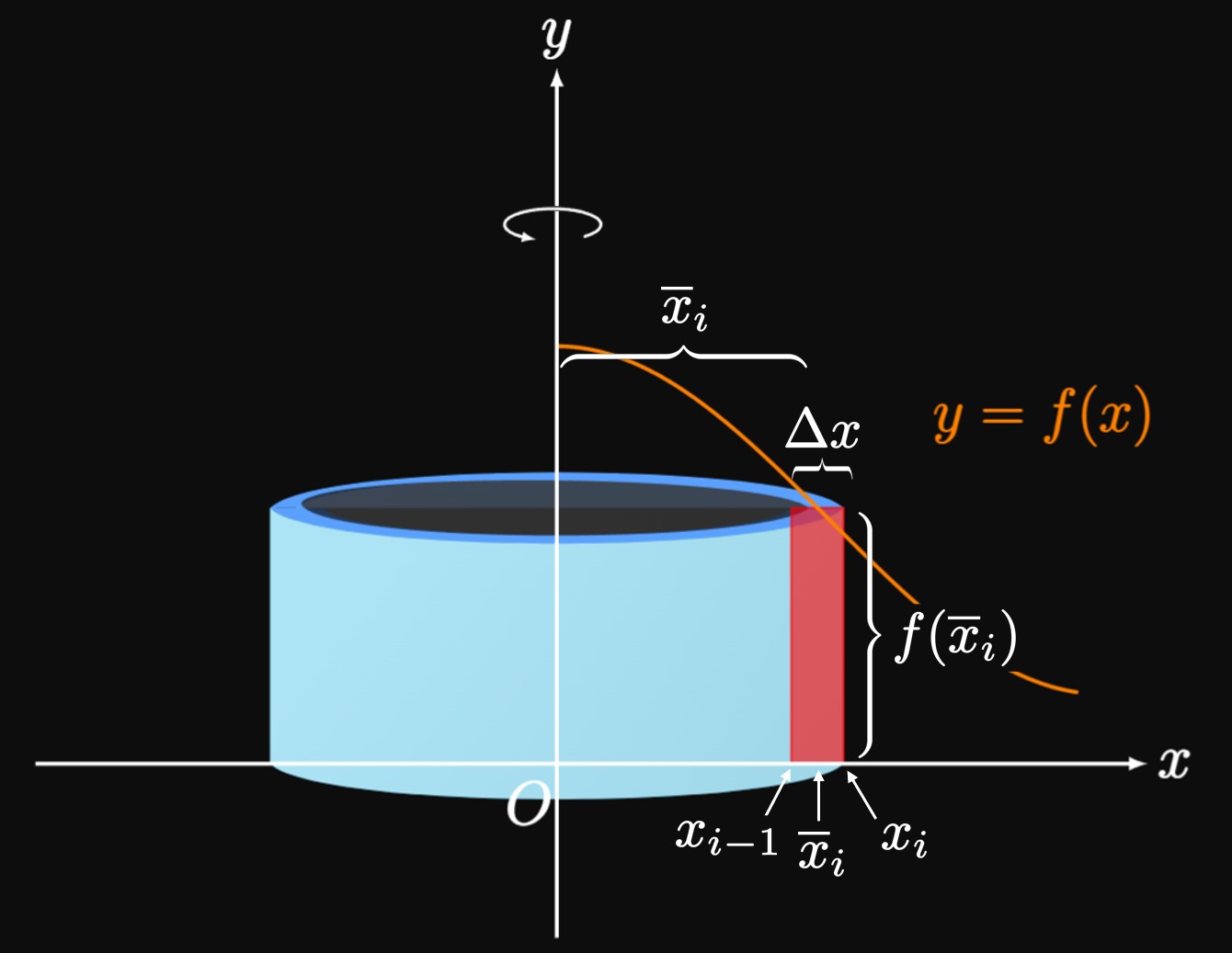

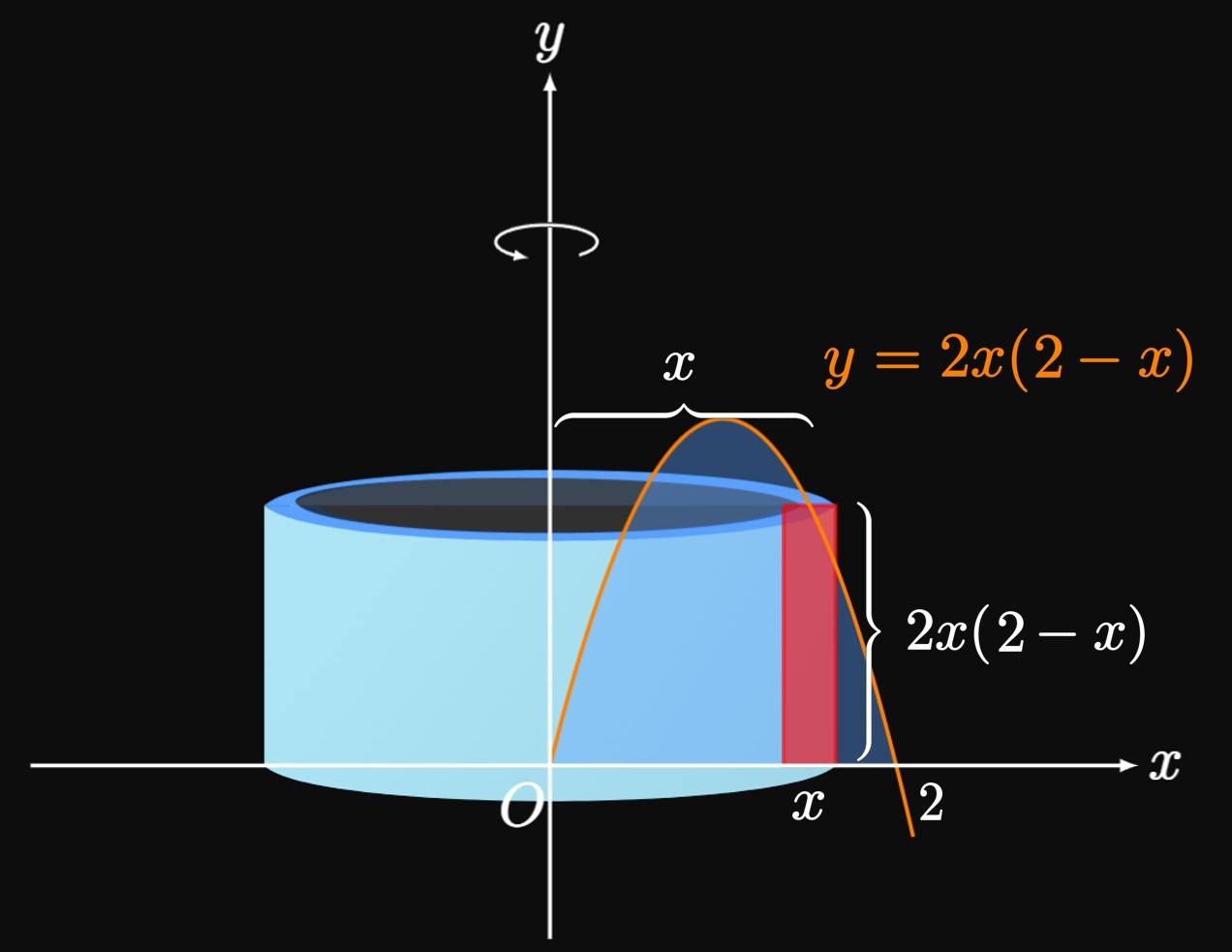

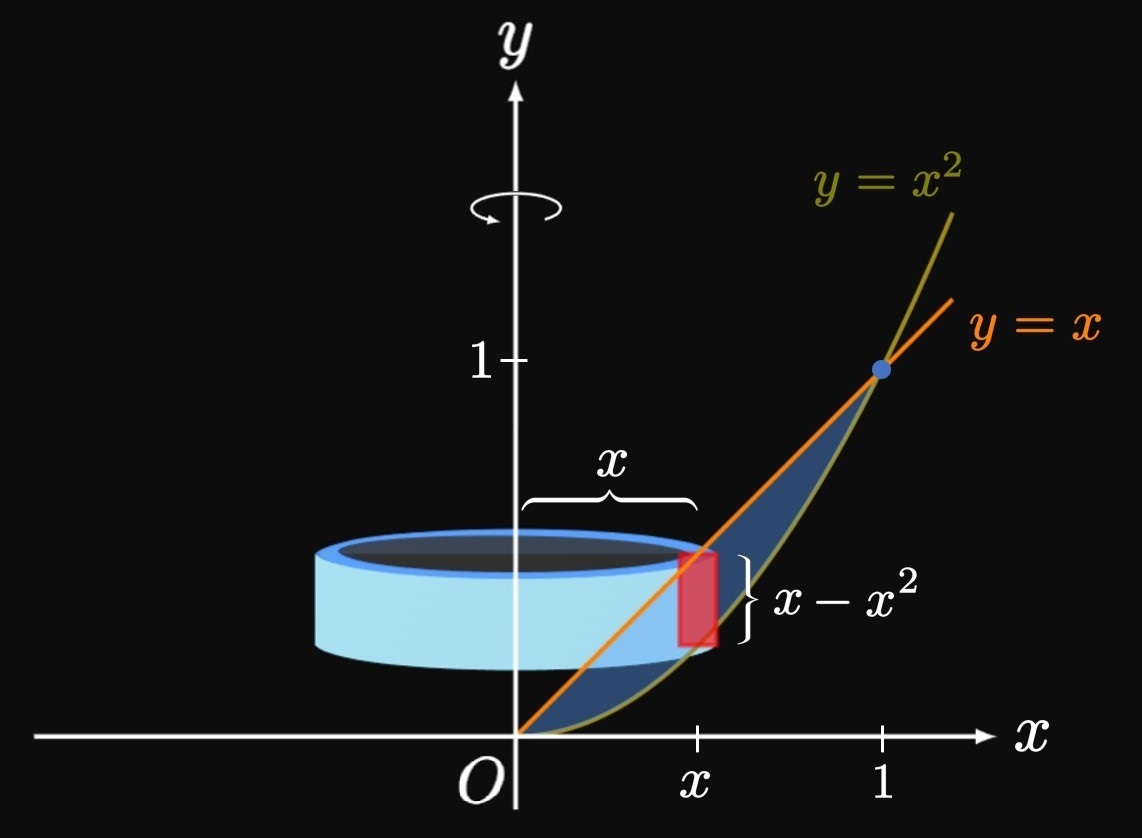

Let's begin by considering the region \(R\) under the curve \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b\) in the first quadrant (Figure 1A). If we rotate this region about the \(y\)-axis, then we obtain a solid of revolution. We could use the Washer Method to calculate its volume, but let's use a new approach: We cut the region into \(n\) rectangles with endpoints \(a = x_0, x_1,\) \(\dots, x_{n - 1}, x_n = b\) and equal width \(\Delta x.\) We'll rotate each rectangle about the \(y\)-axis and sum the volumes of the resulting cylindrical shells. (See Figure 1B.) Let \(\overline x_i\) be the midpoint of the general subinterval \(\parbr{x_{i - 1}, x_i};\) an approximating rectangle in this subinterval therefore has height \(f(\overline x_i).\) (See Figure 2.) Rotating this rectangle about the \(y\)-axis produces a cylindrical shell whose inner radius is \(x_{i - 1}\) and outer radius is \(x_i.\) Its volume is therefore the difference in volumes of the cylinders. Performing some algebraic manipulation, we find the shell's volume to be \[ \ba \Delta V &= \underbrace{\pi x_i^2 f(\overline x_i)}_{\substack{\text{volume of} \\ \text{outer cylinder}}} - \underbrace{\pi x_{i - 1}^2 f(\overline x_i)}_{\substack{\text{volume of} \\ \text{inner cylinder}}} \nl &= \pi f(\overline x_i) \par{x_i^2 - x_{i - 1}^2} \nl &= \pi f(\overline x_i) \par{x_i + x_{i - 1}} \par{x_i - x_{i - 1}} \nl &= 2 \pi f(\overline x_i) \par{\frac{x_i + x_{i - 1}}{2}} \par{x_i - x_{i - 1}} \pd \ea \] But since \(\overline x_i\) is the midpoint of the subinterval, we have \[ \ba \Delta V &= 2 \pi f(\overline x_i) \overline x_i \par{x_i - x_{i - 1}} \nl &= 2 \pi f(\overline x_i) \overline x_i \Delta x \pd \ea \] This is the expression we need. Rotating all \(n\) rectangles about the \(y\)-axis and summing the volumes of their corresponding shells, we get \[ V \approx \sum_{i = 1}^n 2 \pi \overline x_i f(\overline x_i) \Delta x \pd \] We recognize this expression as a Riemann sum for the function \(2 \pi x f(x).\) As we increase \(n,\) the shells become thinner and therefore better encapsulate the solid of revolution. Hence, the sum becomes the exact volume \(V\) if we let \(n \to \infty.\) So we have \begin{align} V &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i = 1}^n 2 \pi \overline x_i f(\overline x_i) \Delta x \nonum \nl &= 2 \pi \int_a^b x f(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:shell-f} \end{align} This formula is a special case of the Shell Method for rotating about the \(y\)-axis. But the same geometric basis allows us to use this method for rotating about any line.

In Example 1 the Shell Method was an easy way to calculate the volume of the solid of revolution. Alternatively, we could instead use the Washer Method by finding the graph's relative maximum and reexpressing \(y = 2x(2 - x)\) to be a function of \(y\)—a much more difficult process. But the Shell Method is an alternative to the Disk Method or Washer Method, so we should attain the same volume regardless.

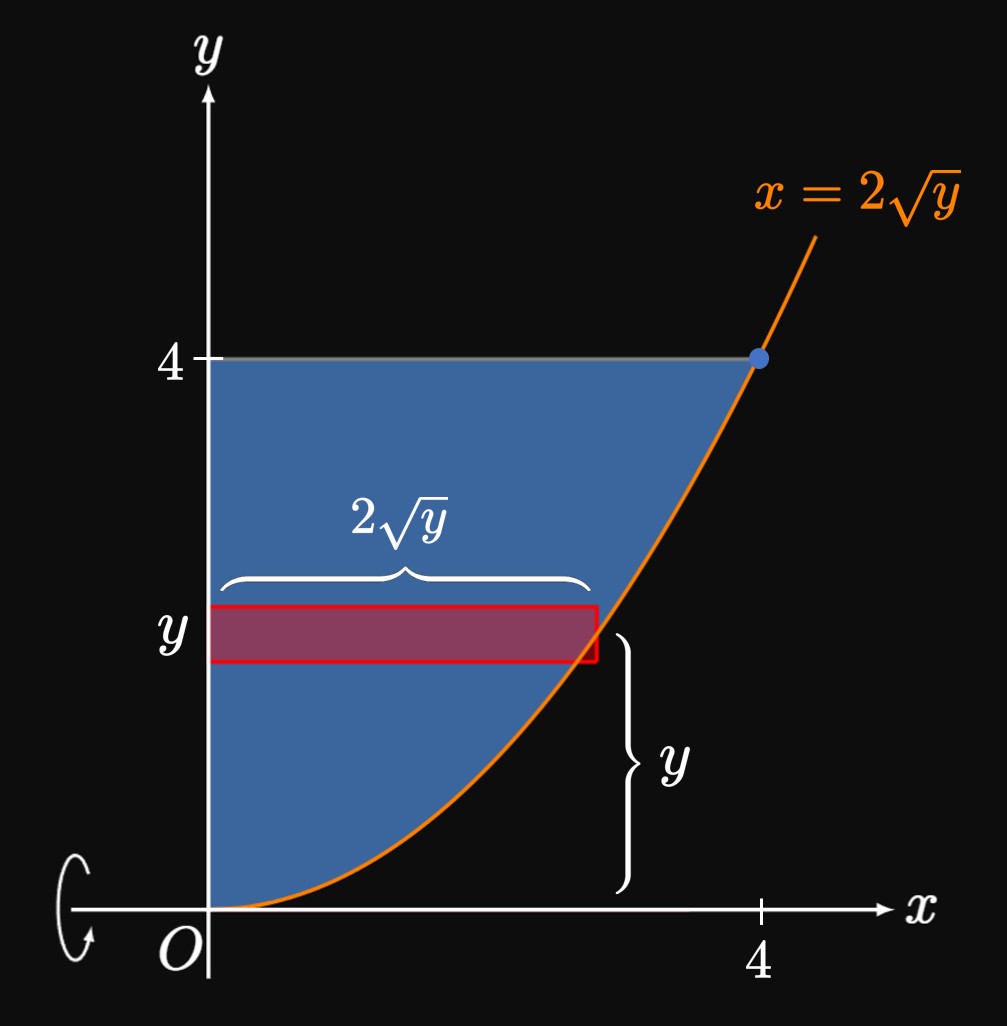

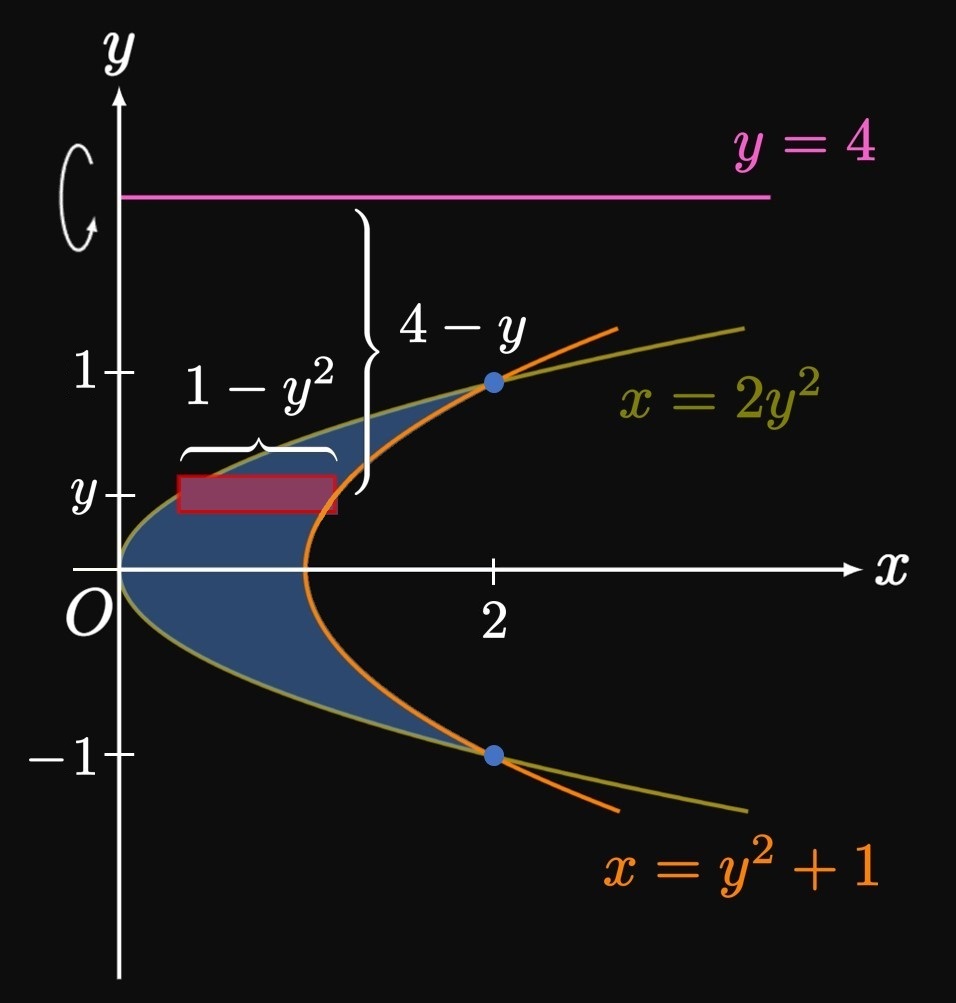

Generalized Shell Method Let's reapply the line of reasoning used to attain \(\eqref{eq:shell-f}.\) When we use the Shell Method, we construct rectangles parallel to the axis of revolution. For example, in Example 1 we visualized rotating a vertical approximating rectangle about a vertical line (the \(y\)-axis). (Conversely, approximating rectangles are perpendicular to the axis of revolution in the Disk Method and Washer Method.) Suppose that a region is bounded from \(x = a\) to \(x = b,\) and that an approximating rectangle at \(x\) has height \(h(x)\) and is a distance \(r(x)\) from the vertical axis of revolution. Then the volume of the solid of revolution is \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_a^b r(x) h(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:shell-x} \end{equation} \(\eqrefer{eq:shell-f}\) is a special case of \(\eqref{eq:shell-x}\) with \(r(x) = x\) and \(h(x) = f(x).\) Likewise, suppose that a region is bounded from \(y = c\) to \(y = d,\) and that a horizontal approximating rectangle at \(y\) has width \(h(y)\) and sits a distance \(r(y)\) from the horizontal axis of revolution. The corresponding solid of revolution then has volume \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_c^d r(y) h(y) \di y \pd \label{eq:shell-y} \end{equation}

- If a vertical approximating rectangle at \(x\) has height \(h(x)\) and is a distance of \(r(x)\) away from the vertical axis of revolution, then the solid of revolution has volume \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_a^b r(x) h(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:shell-x} \end{equation}

- If a horizontal approximating rectangle at \(y\) has width \(h(y)\) and is a distance of \(r(y)\) away from the horizontal axis of revolution, then the solid of revolution has volume \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_c^d r(y) h(y) \di y \pd \eqlabel{eq:shell-y} \end{equation}

TIP When you solve problems, it is imperative to stay organized: Sketch the bounded region and draw an approximating rectangle. (If you're rotating about a horizontal line, then draw a horizontal approximating rectangle. Likewise, if you're rotating about a vertical line, then draw a vertical approximating rectangle.) Find the rectangle's height (or width) and its distance from the axis of revolution; then use \(\eqref{eq:shell-x}\) or \(\eqref{eq:shell-y}\) as necessary.

In Example 5 it would be very difficult to calculate the volume using the Washer Method. (We would need to construct vertical approximating rectangles.) Hence, the Shell Method was our preferred resource. But the converse could also be true: The volume of the solid in Example 5.3-3 is easily computed using the Disk Method, but using the Shell Method would be grueling. Yet in other problems, it is impossible to use other methods. For example, if we wish to rotate a region about a vertical axis but cannot express all quantities in terms of \(y,\) then we can't use the Disk Method or Washer Method; we can only resort to the Shell Method. The Shell Method does not supersede the Disk Method and Washer Method; it is simply an alternative resource we can use if possible. Thus, be flexible and select the easiest method.

The Shell Method is an alternative to the Disk Method and Washer Method. When we apply it, we construct approximating rectangles parallel to the axis of revolution (instead of perpendicular as with the Disk Method and Washer Method). If the region in the first quadrant bounded by \(y = f(x)\) and the \(x\)-axis from \(x = a\) to \(x = b\) is rotated about the \(y\)-axis, then the volume of the generated solid is \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_a^b x f(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:shell-f} \end{equation} More generally, we have the following formulas:

- If a vertical approximating rectangle at \(x\) has height \(h(x)\) and is a distance of \(r(x)\) away from the vertical axis of revolution, then the solid of revolution has volume \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_a^b r(x) h(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:shell-x} \end{equation}

- If a horizontal approximating rectangle at \(y\) has width \(h(y)\) and is a distance of \(r(y)\) away from the horizontal axis of revolution, then the solid of revolution has volume \begin{equation} V = 2 \pi \int_c^d r(y) h(y) \di y \pd \eqlabel{eq:shell-y} \end{equation}