2.3: Product Rule and Quotient Rule

We've differentiated sums and differences of functions. In this section we extend our scope to differentiate products and quotients of functions. We discuss the following topics:

Product Rule

A product is the result of multiplication; for example, the product of the numbers \(5\) and \(3\) is \(15.\) The Product Rule enables us to differentiate functions in the form \(f(x)g(x),\) where \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions. The Product Rule states \[\deriv{}{x} \parbr{f(x) g(x)} = \deriv{}{x} [f(x)] \cdot g(x) + f(x) \cdot \deriv{}{x} [g(x)] \pd\] This form can be condensed. For convenience, we write \(f(x)\) as \(f\) and \(g(x)\) as \(g.\) [In general, \(f\) is shorthand for \(f(x)\) and \(g\) is shorthand for \(g(x).\)] If primes denote derivatives with respect to \(x,\) then a condensed version of the Product Rule is \begin{equation} \par{fg}' = f'g + fg' \pd \label{eq:product-rule} \end{equation} Note the alternating pattern of the primes. In words, the Product Rule asserts that the derivative of a product of two functions is the derivative of the first function multiplied by the second function, plus the first function multiplied by the derivative of the second function.

It is important to note that, generally, the derivative of a product of two functions isn't the product of their derivatives. For example, if \(f(x) = x\) and \(g(x) = x^2,\) then the Power Rule (from Section 2.2) gives \[\par{fg}' = \par{x \cdot x^2}' = \par{x^3}' = 3x^2 \pd\] But \[f' g' = \par{x}' \cdot \par{x^2}' = 1 \cdot 2x \ne 3x^2 \pd\] Thus, \((fg)' \ne f' g'.\)

PROOF OF THE PRODUCT RULE Let \(f\) and \(g\) be differentiable functions. By the limit definition of a derivative, the derivative of \(f(x) g(x)\) is given by \[\deriv{}{x} \parbr{f(x)g(x)} = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) g(x + h) - f(x) g(x)}{h} \pd\] To find an equivalent expression involving the derivatives of \(f\) and \(g,\) we add and subtract the same quantity \(f(x + h) g(x).\) Doing so and using limit laws (from Section 1.2) demonstrate \begin{align} \deriv{}{x} \parbr{f(x)g(x)} &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) g(x + h) \orange{- f(x + h) g(x) + f(x + h) g(x)} - f(x) g(x)}{h} \nonumber \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} \parbr{f(x + h) \, \frac{g(x + h) - g(x)}{h} + g(x) \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h}} \nonumber \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} f(x + h) \cdot \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{g(x + h) - g(x)}{h} + g(x) \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} \nonumber \nl &= f(x) g'(x) + g(x) f'(x) \nonumber \nl &= f'g + fg' \eqlabel{eq:product-rule} \pd \end{align} \[\qedproof\]

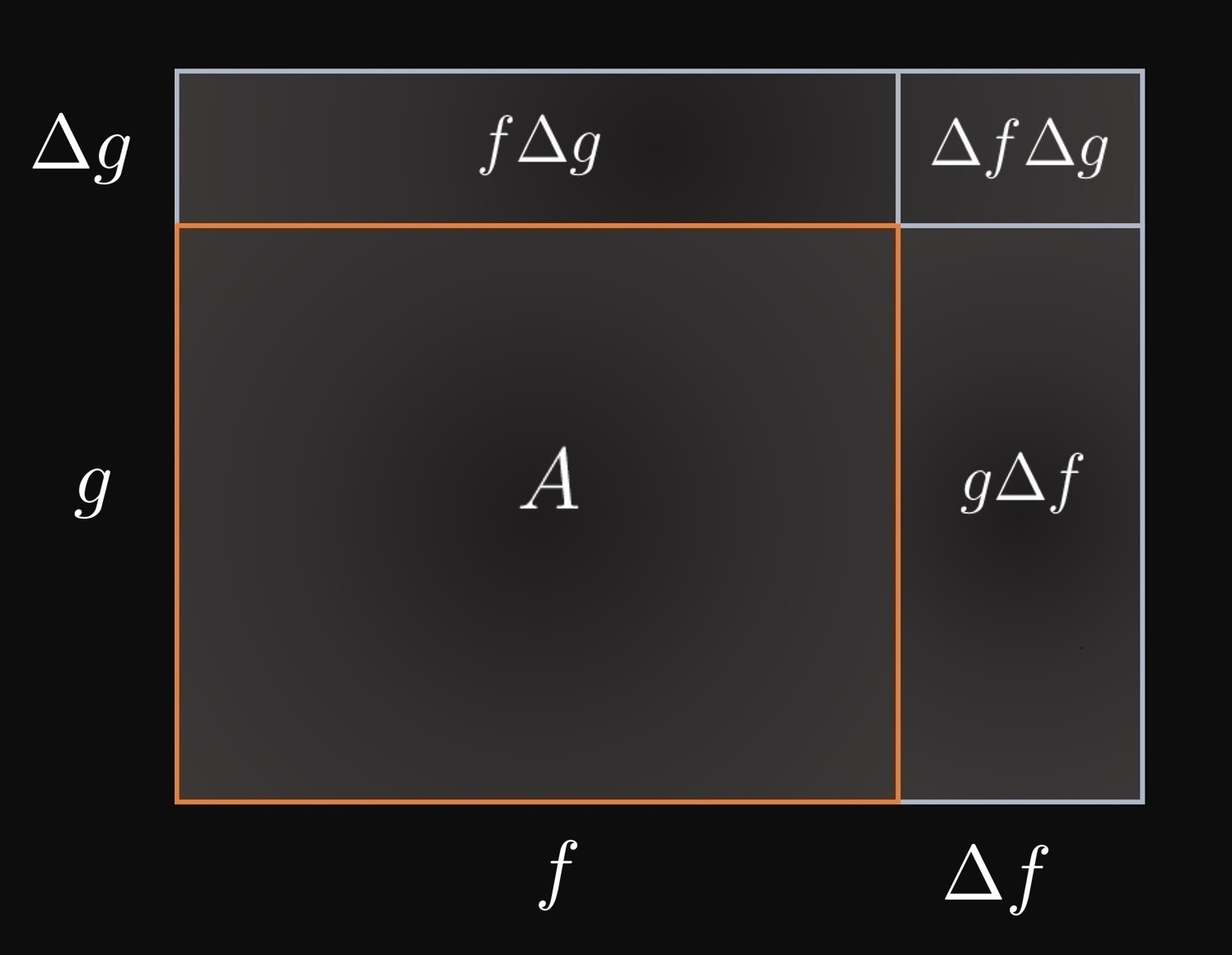

Visualization of the Product Rule Let \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) be positive differentiable functions. As \(x\) is changed by some amount \(\Delta x,\) then \[\Delta f = f(x + \Delta x) - f(x) \and \Delta g = g(x + \Delta x) - g(x) \pd\] Observe that \(\Delta f \to 0\) and \(\Delta g \to 0\) as \(\Delta x \to 0.\) We now interpret \(f\) and \(g\) geometrically. In Figure 1, a rectangle of area \(A\) has horizontal length \(f\) and vertical length \(g.\) Then \(A = fg.\) Suppose that the rectangle's sides are expanded horizontally by \(\Delta f\) and vertically by \(\Delta g.\) By geometry, the change in area is given by \[\Delta A = f \Delta g + g \Delta f + \Delta f \Delta g \pd\] Dividing both sides of the equation by \(\Delta x\) shows \[ \diffDelta{A}{x} = f \diffDelta{g}{x} + g \diffDelta{f}{x} + \Delta f \diffDelta{g}{x} \pd \] If we let \(\Delta x\) approach \(0,\) then all the ratios become derivatives. Using limit laws (from Section 1.2), we see \begin{align} \deriv{A}{x} &= \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \diffDelta{A}{x} \nonumber \nl &= \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \par{f \diffDelta{g}{x} + g \diffDelta{f}{x} + \Delta f \diffDelta{g}{x}} \nonumber \nl &= f \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \diffDelta{g}{x} + g \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \diffDelta{f}{x} + \par{\lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \Delta f} \par{\lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \diffDelta{g}{x}} \nonumber \nl &= f \deriv{g}{x} + g \deriv{f}{x} + 0 \cdot \par{\lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \diffDelta{g}{x}} \nonumber \nl &= f'g + fg' \pd \eqlabel{eq:product-rule} \end{align}

Method 1 Letting \(f(x) = 2x - 1\) and \(g(x) = \sqrt x,\) we see \[f'(x) = 2 \and g'(x) = \frac{1}{2 \sqrt x} \pd\] The Product Rule, as in \(\eqref{eq:product-rule},\) therefore gives \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \parbr{\par{2x - 1} \sqrt x} &= f'g + fg' \nl &= (2) \sqrt x + (2x - 1) \cdot \frac{1}{2 \sqrt x} \nl &= 2 \sqrt x + \frac{2x - 1}{2 \sqrt x} \nl &= \boxed{\frac{6x - 1}{2 \sqrt x}} \ea \]

Method 2 We write \(\sqrt x\) as \(x^{1/2}\) and expand the product, as follows: \[\par{2x - 1} \cdot x^{1/2} = 2 x^{3/2} - x^{1/2} \pd\] Combining the Difference and Constant Multiple Rules for Derivatives (from Section 2.1) with the Power Rule, we see \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \par{2 x^{3/2} - x^{1/2}} &= 2 \deriv{}{x} \par{x^{3/2}} - \deriv{}{x} \par{x^{1/2}} \nl &= 2 \par{\tfrac{3}{2} x^{1/2}} - \par{\tfrac{1}{2} x^{-1/2}} \nl &= 3 \sqrt x - \frac{1}{2 \sqrt x} \nl &= \boxed{\frac{6x - 1}{2 \sqrt x}} \ea \] Method 2 is easier to use than Method 1. Thus, be aware of shortcuts that enable you to avoid the Product Rule.

Quotient Rule

A quotient is the result of division; for example, the quotient of \(12\) divided by \(6\) is \(2.\) To differentiate expressions in the form \(f(x)/g(x),\) where \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions, we use the Quotient Rule, which states \[\deriv{}{x} \parbr{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}} = \frac{f'(x) g(x) - f(x) g'(x)}{[g(x)]^2} \cma\] given that \(g(x) \ne 0.\) Or if primes denote derivatives with respect to \(x,\) then we can write a condensed form of the Quotient Rule: \begin{equation} \par{\frac{f}{g}}' = \frac{f'g - fg'}{g^2} \cma g \ne 0 \pd \label{eq:quotient-rule} \end{equation} The expression \(f'g - fg'\) may look similar to the Product Rule, as in \(\eqref{eq:product-rule},\) but don't disregard the negative sign. The following mnemonic may help you remember the Quotient Rule:

The derivative is Low Dee High minus High Dee Low, all over the square of what's below,where Dee indicates the differentiation operator, High denotes the numerator, and Low references the denominator. Accordingly, Dee High denotes \(f'\) and Dee Low references \(g'.\)

PROOF OF THE QUOTIENT RULE To prove the Quotient Rule, we employ a clever trick by adding and subtracting the same quantity. The limit definition of a derivative states \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \parbr{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}} &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\ds \frac{f(x + h)}{g(x + h)} - \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}{h} \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{g(x) f(x + h) - f(x) g(x + h)}{h g(x) g(x + h)} \pd \ea \] We now add and subtract the quantity \(f(x) g(x)\) so that the derivatives \(f'(x)\) and \(g'(x)\) appear from this fraction: \begin{align} \deriv{}{x} \parbr{\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}} &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{g(x) f(x + h) \orange{- f(x)g(x) + f(x)g(x)} - f(x) g(x + h)}{h g(x) g(x + h)} \nonumber \nl &= \frac{\ds \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{g(x) \parbr{f(x + h) - f(x)}}{h} - \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x) \parbr{g(x + h) - g(x)}}{h}}{\ds \lim_{h \to 0} [g(x) g(x + h)]} \nonumber \nl &= \frac{\ds g(x) \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} - f(x)\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{g(x + h) - g(x)}{h}}{\ds g(x) \lim_{h \to 0} g(x + h)} \nonumber \nl &= \frac{g(x) f'(x) - f(x) g'(x)}{[g(x)]^2} \nonumber \nl &= \frac{f'g - fg'}{g^2} \eqlabel{eq:quotient-rule} \end{align} \[\qedproof\]

It's important to be vigilant: Some quotients of functions don't require the Quotient Rule, since it may be easier to first simplify them into sums of powers. A good example is \[\frac{x^4 - x^2 + \sqrt x}{x} \cma\] which we can simplify as \[\frac{x^4 - x^2 + x^{1/2}}{x} = x^3 - x + x^{-1/2} \pd\] Differentiating this new form is far easier, as it only requires the Power Rule.

Derivatives of Tangent, Secant, Cosecant, and Cotangent

In Section 2.2 we found that \[\deriv{}{x} \par{\sin x} = \cos x \and \deriv{}{x} \par{\cos x} = - \sin x \pd\] The functions \(\tan x,\) \(\sec x,\) \(\csc x,\) and \(\cot x\) can all be expressed in terms of sine and cosine, as follows: \[ \baat{2} \tan x &= \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} \lspace \cot x &&= \frac{\cos x}{\sin x} \nl \sec x &= \frac{1}{\cos x} \lspace \csc x &&= \frac{1}{\sin x} \pd \eaat \] Thus, the Quotient Rule enables us to differentiate all four functions.

Derivative of Tangent Since \(\tan x = \sin x/\cos x,\) the Quotient Rule shows \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \par{\tan x} &= \frac{(\cos x) \cos x - \sin x (-\sin x)}{\cos^2 x} \nl &= \frac{\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x} \pd \ea \] The Pythagorean identity states that \(\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x = 1,\) so \[\deriv{}{x} \par{\tan x} = \frac{1}{\cos^2 x} = \boxed{\sec^2 x}\]

As we've seen through the derivatives of \(\tan x\) and \(\sec x,\) understanding the Quotient Rule allows us to differentiate all six standard trigonometric functions. We attain the following table of trigonometric derivatives, which are so important that memorizing them is essential.

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\sin x} = \cos x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\cos x} = -\sin x\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\tan x} = \sec^2 x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\cot x} = -\csc^2 x\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\sec x} = \sec x \tan x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\csc x} = -\csc x \cot x\) |

Up to this point, you may have questioned why we use the reciprocal trigonometric functions (tangent, secant, cosecant, and cotangent). But we now appreciate how reciprocal functions enable us to easily communicate derivatives of otherwise complicated compositions with sine and cosine. The following tips may help you remember these derivatives.

- Any trigonometric function containing the prefix co- (cosine, cosecant, and cotangent) has a negative sign in its derivative.

- Secant and cosecant are the only trigonometric functions whose derivatives include themselves as factors.

- Tangent and cotangent are the only trigonometric functions whose derivatives are squared.

Product Rule The Product Rule enables us to differentiate products of functions of the form \(f(x) g(x).\) If \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions, then \begin{equation} \par{fg}' = f'g + fg' \pd \eqlabel{eq:product-rule} \end{equation} Observe the alternating pattern of the primes. Remember that the derivative of a product is not a product of derivatives; namely, \(\par{fg}' \ne f' g'.\)

Quotient Rule The Quotient Rule enables us to differentiate quotients of functions in the form \(f(x)/g(x)\) where \(g(x) \ne 0.\) If \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions, then \begin{equation} \par{\frac{f}{g}}' = \frac{f'g - fg'}{g^2} \cma g \ne 0 \pd \eqlabel{eq:quotient-rule} \end{equation} Do not forget the negative sign. The derivative of a quotient is not a quotient of derivatives; that is, \((f/g)' \ne\) \(f'/g'.\) The algebra involved in differentiation can be wearying; the only remedy is to continue practicing problems. Doing so will help you improve your speed and make fewer mistakes.

Derivatives of Tangent, Secant, Cosecant, and Cotangent The Quotient Rule enables us to differentiate the functions \(\tan x,\) \(\sec x,\) \(\csc x,\) and \(\cot x.\) The derivatives are given as follows:

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\sin x} = \cos x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\cos x} = -\sin x\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\tan x} = \sec^2 x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\cot x} = -\csc^2 x\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\sec x} = \sec x \tan x\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\csc x} = -\csc x \cot x\) |

The following tips may help you remember these derivatives.

- Any trigonometric function containing the prefix co- (cosine, cosecant, and cotangent) has a negative sign in its derivative.

- Secant and cosecant are the only trigonometric functions whose derivatives include themselves as factors.

- Tangent and cotangent are the only trigonometric functions whose derivatives are squared.