2.5: Implicit Differentiation and Differentiating Inverse Functions

We have differentiated functions in the form \(y = f(x)\). But sometimes it's impossible to express \(y\) as a function of \(x.\) In these cases, we write implicit equations to relate \(x\) and \(y.\) The method of Implicit Differentiation enables us to find slopes to a curve without needing to solve for \(y\) explicitly. We apply Implicit Differentiation to differentiate inverse functions, which make up the remaining functions we have yet to discuss. We cover the following topics:

- Implicit Differentiation

- Differentiating Inverse Functions

- Differentiating Inverse Trigonometric Functions

Implicit Differentiation

An equation of the form \(y = f(x)\) is called an explicit equation, examples of which are \(y = x - 4\) and \(y = x^2 - 4x.\) Conversely, an implicit equation relates \(x\) and \(y\) through an equation in which \(y\) isn't expressed as a function of \(x.\) Examples of implicit equations are \[x^2 + xy = 6 \and 9x - 4y = 0 \pd\] Implicit Differentiation is the process by which we obtain \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) by treating \(y\) as a function of \(x\) and applying the Chain Rule (from Section 2.4).

Many curves are best expressed as implicit equations.

For example, the equation of a unit circle is

\begin{equation}

x^2 + y^2 = 1 \pd \label{eq:unit-circle}

\end{equation}

The curve generated by a unit circle contains all the coordinates \((x, y)\)

for which \(\eqref{eq:unit-circle}\) holds true.

Writing the implicit equation \(\eqref{eq:unit-circle}\)

enables us to represent the entire circle without needing to solve for \(y.\)

To determine the slope of this circle at any point \((x, y),\)

we use Implicit Differentiation to attain \(\textderiv{y}{x} \col\)

We treat \(y\) as \(y(x),\) a function of \(x,\)

so \(\eqRef{eq:unit-circle}\) should be thought of as

\[x^2 + [y(x)]^2 = 1 \pd\]

Now we differentiate both sides with respect to \(x,\)

using the Chain Rule to differentiate \(y(x).\) Doing so gives

\[2x + 2y \deriv{y}{x} = 0 \pd\]

Now we solve for \(\textDeriv{y}{x} \col\)

\[\deriv{y}{x} = -\frac{x}{y} \pd\]

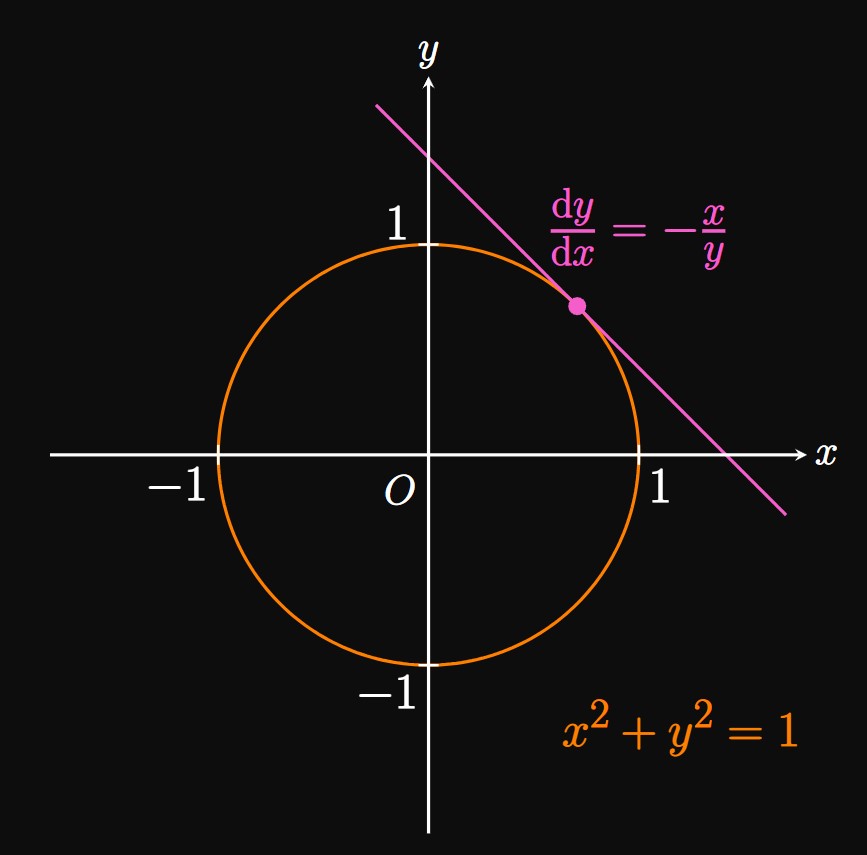

Figure 1 shows a diagram of a unit circle with a tangent line. At \((0, -1)\) and \((0, 1),\) the circle has horizontal tangents because \(\textderiv{y}{x} = 0.\) Conversely, at \((-1, 0)\) and \((1, 0)\) the circle has vertical tangents and so \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) is undefined. Hence, \(\textDeriv{y}{x} = -x/y\) appears mathematically accurate. Solving for \(y\) in \(\eqref{eq:unit-circle}\) would yield two explicit equations, \(y = f(x) = \sqrt{1 - x^2}\) and \(y = g(x) = -\sqrt{1 - x^2}.\) The graph of \(f\) represents the top half of the unit circle, while the graph of \(g\) represents the bottom half. Indeed, we see \[ \baat{2} f'(x) &= \frac{-x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \lspace g'(x) &&= \frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \nl &= \frac{-x}{y} &&= \frac{-x}{-\sqrt{1 - x^2}} = \frac{-x}{y} \pd \eaat \] These results agree with our result \(\textDeriv{y}{x} = -x/y,\) obtained from Implicit Differentiation.

In some cases, we can directly solve for \(y\) in an implicit equation, just as we did with \(\eqref{eq:unit-circle}.\) Similar to the unit circle example, the implicit equation \(xy = 1\) can be written explicitly as \(y = 1/x.\) Thus, \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) can be found by simply applying the Power Rule—no Implicit Differentiation needed. Yet in many cases, solving for \(y\) explicitly is impossible and Implicit Differentiation is needed to acquire \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\) Let's establish a set of steps to perform Implicit Differentiation.

- Differentiate both sides of the implicit equation with respect to \(x.\)

- On the left side, collect all the terms containing the factor \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\) Move all the other terms to the right side of the equation.

- Factor \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) out of the left side of the equation.

- Solve for \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\)

- We first differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to \(x.\) We use the Chain Rule to differentiate \(y,\) which we treat as a function of \(x.\) \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} (2x^3y - xy^2) &= \deriv{}{x}(16) \nl \deriv{}{x} \par{2x^3 y} - \deriv{}{x} \par{xy^2} &= 0 \nl 2 \left(3x^2 y + x^3 \deriv{y}{x} \right) - \left(y^2 + 2xy \deriv{y}{x} \right)&= 0 \pd \ea \]

- We collect all terms containing \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) on the left side. We move all other terms to the right side. Doing so, we get \[2x^3 \deriv{y}{x} - 2xy \deriv{y}{x} = y^2 - 6x^2 y \pd\]

- Factoring out \(\textderiv{y}{x},\) we attain \[\deriv{y}{x} \par{2x^3 - 2xy} = y^2 - 6x^2y \pd\]

- To solve for \(\textderiv{y}{x},\) we divide both sides by \((2x^3 - 2xy) \col\) \[\deriv{y}{x} = \boxed{\frac{y^2 - 6x^2 y}{2x^3 - 2xy}}\]

Let's first find \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\)

- Differentiating both sides of the implicit equation with respect to \(x,\) we get \[ 2x y + x^2 \deriv{y}{x} = (0) - y^2 - 2xy \deriv{y}{x} \pd \]

- We move every term involving \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) to the left side of the equation; we place all the other terms on the right side. Doing so gives \[x^2 \deriv{y}{x} + 2xy \deriv{y}{x} = -y^2 - 2xy \pd\]

- On the left side, we factor out the factor \(\textderiv{y}{x} \col\) \[\deriv{y}{x} \par{x^2 + 2xy} = -y^2 - 2xy \pd\]

- Solving for \(\textderiv{y}{x},\) we see \begin{equation} \deriv{y}{x} = \frac{-y^2 - 2xy}{x^2 + 2xy} \pd \label{eq:dy/dx-tangents} \end{equation}

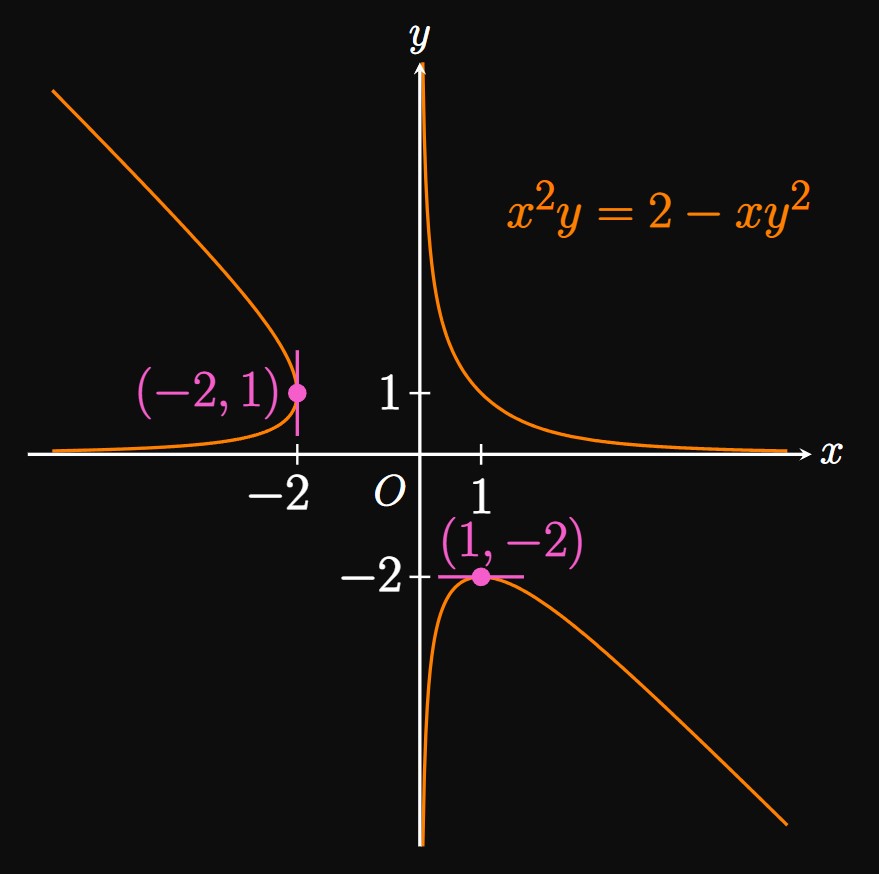

Horizontal Tangents The curve has a horizontal tangent when \(\textderiv{y}{x} = 0.\) For an implicit curve, we must describe locations as points—that is, we need both \(x\) and \(y.\) In \(\eqref{eq:dy/dx-tangents}\) we observe that \(\textderiv{y}{x} = 0\) when the numerator is \(0\) and the denominator is nonzero. So solving shows \[-y^2 - 2xy = 0 \implies x = -\tfrac{1}{2} y \pd\] Substituting this expression into \(x^2 y = 2 - xy^2,\) we see \[ \ba \par{-\tfrac{1}{2} y}^2 y &= 2 - \par{-\tfrac{1}{2} y} y^2 \nl \tfrac{1}{4} y^3 &= 2 + \tfrac{1}{2} y^3 \nl y^3 &= -8 \nl \implies y &= -2 \pd \ea \] The \(x\)-coordinate corresponding to \(y = -2\) is \(x = -\tfrac{1}{2}(-2)\) \(= 1.\) Thus, the curve has a horizontal tangent at the point \(\boxed{(1, -2)}.\)

Vertical Tangents The curve has a vertical tangent when the denominator of \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) is \(0\) and the numerator is nonzero. In \(\eqref{eq:dy/dx-tangents}\) equating \(x^2 + 2xy\) to \(0\) shows \[x(x + 2y) = 0 \implies x = 0 \cma -2y \pd\] (We ignore the solution \(x = 0\) because it does not satisfy the implicit equation \(x^2 y = 2 - xy^2.\)) Substituting \(x = -2y\) into the implicit equation shows \[ \ba \par{-2y}^2 y &= 2 - (-2y) y^2 \nl 4y^3 &= 2 + 2y^3 \nl 2y^3 &= 2 \nl \implies y &= 1 \pd \ea \] Thus, \(x = -2(1) = -2.\) So the curve has a vertical tangent at the point \(\boxed{(-2, 1)}.\) (See Figure 2.)

Finding \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) We begin by finding \(\textderiv{y}{x},\) as follows: \begin{align} \deriv{}{x} \par{2x^3 + 9y^2 - 12y} &= \deriv{}{x}(5) \nonum \nl 6x^2 + 18 y \deriv{y}{x} - 12 \deriv{y}{x} &= 0 \nonum \nl \deriv{y}{x} \par{18y - 12} &= -6x^2 \nonum \nl \deriv{y}{x} \par{2 - 3y} &= x^2 \nonum \nl \implies \deriv{y}{x} &= \frac{x^2}{2 - 3y} \pd \label{eq:second-deriv-ex} \end{align}

Finding \(\textderivOrder{y}{x}{2}\) To attain the second derivative, we use the Quotient Rule to differentiate \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) with respect to \(x.\) We apply the Chain Rule to differentiate any \(y\) with respect to \(x.\) Whenever we attain \(\textderiv{y}{x},\) we substitute the expression in \(\eqref{eq:second-deriv-ex}.\) We therefore see \[ \ba \derivOrder{y}{x}{2} &= \frac{\ds (2x)(2 - 3y) - x^2 \par{-3 \deriv{y}{x}}}{\par{2 - 3y}^2} \nl &= \frac{\ds (2x)(2 - 3y) + 3x^2 \overbrace{\par{\frac{x^2}{2 - 3y}}}^{\textrm{from} \; \eqref{eq:second-deriv-ex}}}{\par{2 - 3y}^2} \nl &= \boxed{\frac{2x(2 - 3y)^2 + 3x^4}{(2 - 3y)^3}} \ea \]

Differentiating Inverse Functions

A function \(f\) has an inverse function \(\inv f\) if and only if \[f \par{\inv f(x)} = x \or \inv f (f(x)) = x \pd\] In other words, composing a function with its inverse function must return the independent variable. For example, the functions \(\sin x\) and \(\asin x\) are inverse functions, just as \(2^x\) and \(\log_2 x\) are inverse functions.

Let \(f\) be an invertible and differentiable function. To differentiate its inverse function \(\inv f,\) we apply Implicit Differentiation to the equation \[f \par{\inv{f} (x)} = x \pd\] Our goal is to obtain an expression for \(\par{\inv f}'(x),\) the derivative of \(\inv{f} \) with respect to \(x.\) Differentiating both sides with respect to \(x\) shows \begin{flalign} &&f'\par{\inv f(x)} \cdot \par{\inv f}'(x) &= 1 \nonum &\nl \laWord{so} && \par{\inv f}'(x) &= \frac{1}{f'\par{\inv f(x)}} \pd \label{eq:f-inverse-deriv} \end{flalign} Alternatively, if we let \(y = \inv f(x),\) then we see \(x = f(y)\) and \(\textderiv{x}{y} = f'(y).\) Accordingly, \(\eqref{eq:f-inverse-deriv}\) becomes \begin{flalign} &&\par{\inv f}'(x) &= \frac{1}{f'(y)} \nonum &\nl \laWord{or} &&\deriv{y}{x} &= \frac{1}{\textderiv{x}{y}} \pd \label{eq:dx/dy} \end{flalign} Hence, \(\eqref{eq:f-inverse-deriv}\) and \(\eqref{eq:dx/dy}\) are expressions we can use to differentiate an inverse function. \(\eqrefer{eq:dx/dy}\) is convenient if we can express \(x\) as a function of \(y,\) since we obtain a derivative function. Conversely, \(\eqref{eq:f-inverse-deriv}\) can be used to find the derivative of an inverse function at some point. The relationship of \(\eqref{eq:dx/dy}\) is particularly elegant, since it strengthens the magic of Leibniz's notation in connecting the differentials \(\dd x\) and \(\dd y.\)

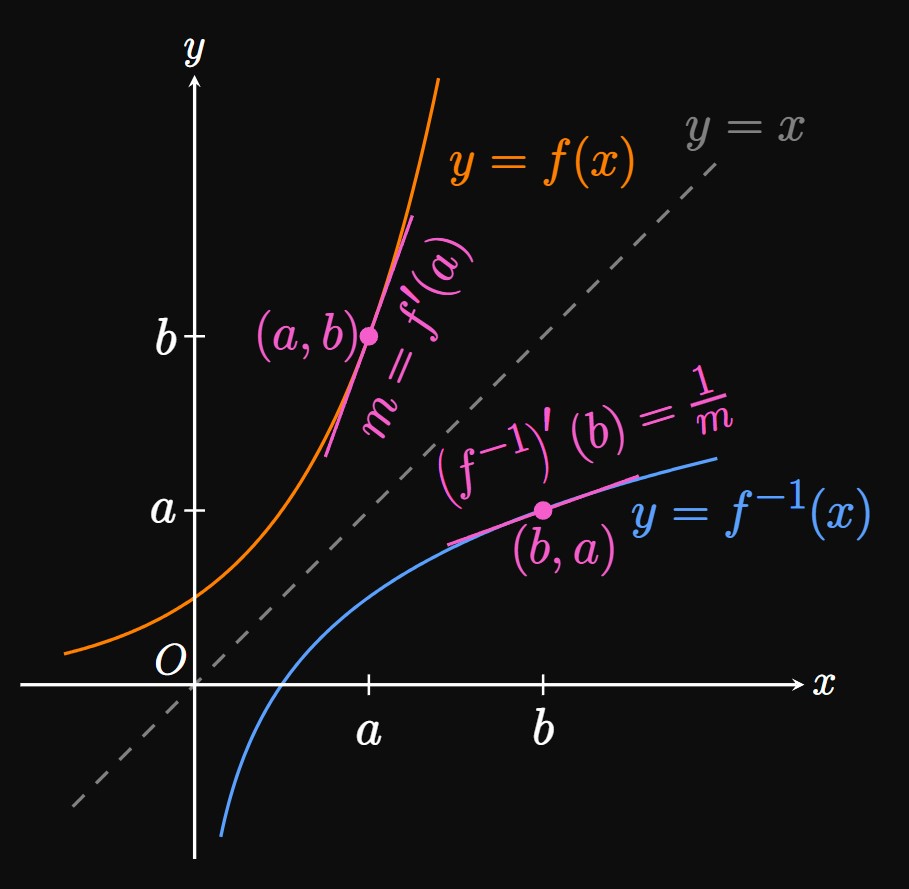

Geometric Interpretation We now discuss a visualization of \(\eqref{eq:f-inverse-deriv} \col\) The graphs of \(y = f(x)\) and \(y = \inv f(x)\) are reflections of each other across the line \(y = x.\) Simply put, any point \((a, b)\) on the graph of \(f\) has a reflection \((b, a)\) on the graph of \(\inv f.\) In Figure 3, observe that the slope of the tangent to \(f\) at the point \((a, b)\) is \(m = f'(a).\) Reflecting this point across \(y = x\) results in \((b, a)\) on the graph of \(\inv f.\) The slope of the tangent to \(\inv f\) at \(x = b\) must be the reciprocal of \(m;\) that is, \[\par{\inv f}'(b) = \frac{1}{m} = \frac{1}{f'(a)} \pd\] But because \(\inv f(b) = a,\) we see \[\par{\inv f}'(b) = \frac{1}{f'\par{\inv f(b)}} \pd\] This equation is just as useful as \(\eqref{eq:f-inverse-deriv},\) since \(b\) can be any value of \(x\) within the domain of \(\inv f.\)

Differentiating Inverse Trigonometric Functions

We now differentiate the inverse trigonometric functions \(\asin x,\) \(\acos x,\) \(\atan x,\) \(\asec x,\) \(\acsc x,\) and \(\acot x.\) All of these derivatives can be obtained by using Inverse Differentiation (or Implicit Differentiation). Let's do an example.

Derivative of \(\asin x\) Let \(y = \asin x.\) As \(\sin\) and \(\asin\) are inverse functions, we have \(x = \sin y.\) Noticing \(\textderiv{x}{y} = \cos y,\) we use \(\eqref{eq:dx/dy}\) to attain \[\deriv{}{x} \par{\asin x} = \frac{1}{\textderiv{x}{y}} = \frac{1}{\cos y} \pd\] We must now relate \(1/\cos y\) to \(x = \sin y \col\) The Pythagorean identity gives \(\sin^2 y + \cos^2 y = 1.\) Since \(-\pi/2 \leq y \leq \pi/2,\) \(\cos y \geq 0\) and we see \begin{flalign} &&\cos y = \sqrt{1 - \sin^2 y} &= \sqrt{1 - x^2} \nonum &\nl \laWord{and} &&\deriv{}{x} \par{\asin x} &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \pd \label{eq:deriv-arcsin} \end{flalign} We could also use Implicit Differentiation to obtain this same result, as follows: \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \par{x} &= \deriv{}{x} \par{\sin y} \nl 1 &= \cos y \deriv{y}{x} \nl \implies \deriv{y}{x} &= \frac{1}{\cos y} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}} \pd \ea \]

Applying the method of Inverse Differentiation (or Implicit Differentiation) gives us formulas for all six inverse trigonometric functions. \(\eqrefer{eq:deriv-arcsin}\) gives the derivative of \(\asin x;\) and we found the derivatives of \(\atan x\) and \(\asec x\) in Example 5 and Example 6, respectively. Differentiating the remaining three functions is similar. The following table displays the derivatives of all the inverse trigonometric functions.

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\asin x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acos x} = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\atan x} = \frac{1}{x^2 + 1}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acot x} = -\frac{1}{x^2 + 1}\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\asec x} = \frac{1}{\abs x \sqrt{x^2 - 1}}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acsc x} = -\frac{1}{\abs x \sqrt{x^2 - 1}}\) |

We suggest that you commit all of these derivatives to memory. The following tips may aid you during this process:

- Any inverse trigonometric function containing the prefix co- (inverse cosine, inverse cosecant, and inverse cotangent) has a negative sign in its derivative.

- Think of three groups of inverse functions: sine and cosine, tangent and cotangent, and secant and cosecant. Members of each group have identical derivatives, apart from the negative sign carried by members with the prefix co-.

- Inverse tangent and inverse cotangent are the only inverse trigonometric functions whose derivatives do not have radicals.

Implicit Differentiation An equation of the form \(y = f(x)\) is called an explicit equation, whereas in an implicit equation \(y\) is not expressed as a function of \(x.\) We use Implicit Differentiation to solve for \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) in implicit equations, as given by the following steps:

- Differentiate both sides of the implicit equation with respect to \(x.\)

- On the left side, collect all the terms containing the factor \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\) Move all the other terms to the right side of the equation.

- Factor \(\textderiv{y}{x}\) out of the left side of the equation.

- Solve for \(\textderiv{y}{x}.\)

Differentiating Inverse Functions Applying Implicit Differentiation provides us with two formulas to differentiate inverse functions: If \(f\) is a differentiable, invertible function, then \[\par{\inv f}'(x) = \frac{1}{f'\par{\inv f(x)}} \pd \eqlabel{eq:f-inverse-deriv}\] Alternatively, if \(y\) is an invertible, differentiable function of \(x,\) then \[\deriv{y}{x} = \frac{1}{\textderiv{x}{y}} \pd \eqlabel{eq:dx/dy}\] You can either use these formulas or perform Implicit Differentiation to attain derivatives of inverse functions.

Differentiating Inverse Trigonometric Functions The method of Inverse Differentiation (or Implicit Differentiation) enables us to differentiate all six inverse trigonometric functions, as shown below:

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\asin x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acos x} = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\atan x} = \frac{1}{x^2 + 1}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acot x} = -\frac{1}{x^2 + 1}\) |

| \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\asec x} = \frac{1}{\abs x \sqrt{x^2 - 1}}\) | \(\ds \deriv{}{x} \par{\acsc x} = -\frac{1}{\abs x \sqrt{x^2 - 1}}\) |

The following tips may help you remember these derivatives:

- Any inverse trigonometric function containing the prefix co- (inverse cosine, inverse cosecant, and inverse cotangent) has a negative sign in its derivative.

- Think of three groups of inverse functions: sine and cosine, tangent and cotangent, and secant and cosecant. Members of each group have identical derivatives, apart from the negative sign carried by members with the prefix co-.

- Inverse tangent and inverse cotangent are the only inverse trigonometric functions whose derivatives do not have radicals.