10.1: Sequences

In many everyday applications, we write numbers in a definite order; for example, we can record the number of natural disasters that occurred every year after 2000. Patterns of numbers are also central to many mathematical contexts; using calculus, we can extend patterns to infinity and analyze their properties. We discuss the following topics:

Defining a Sequence

A sequence is a list of numbers written in a definite order:

\[\{a_1, a_2, a_3, \dots, a_N\} \pd\]

We call \(a_1\) the first term, \(a_2\) the second term,

and \(a_N\) the

Limits of Sequences

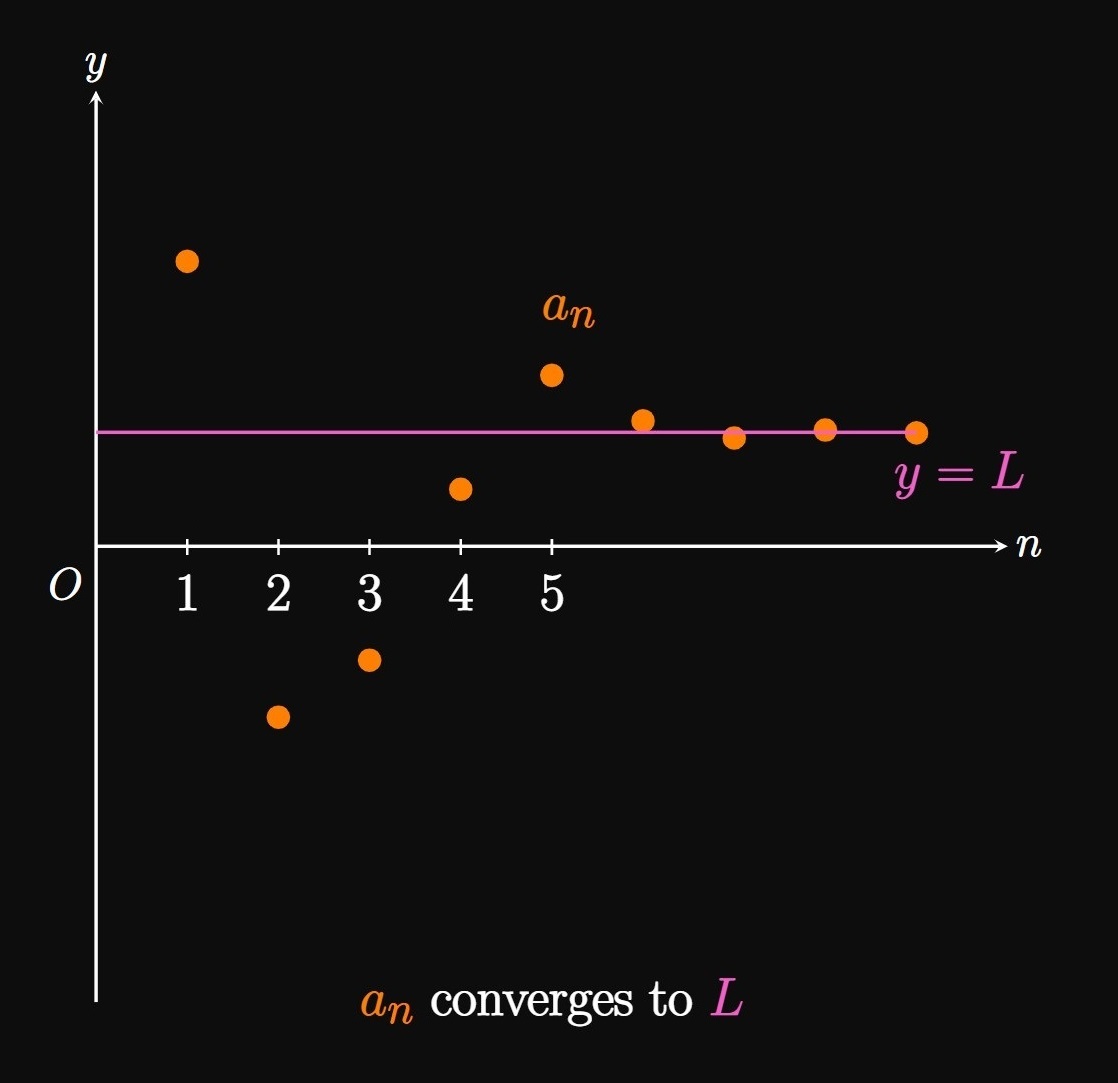

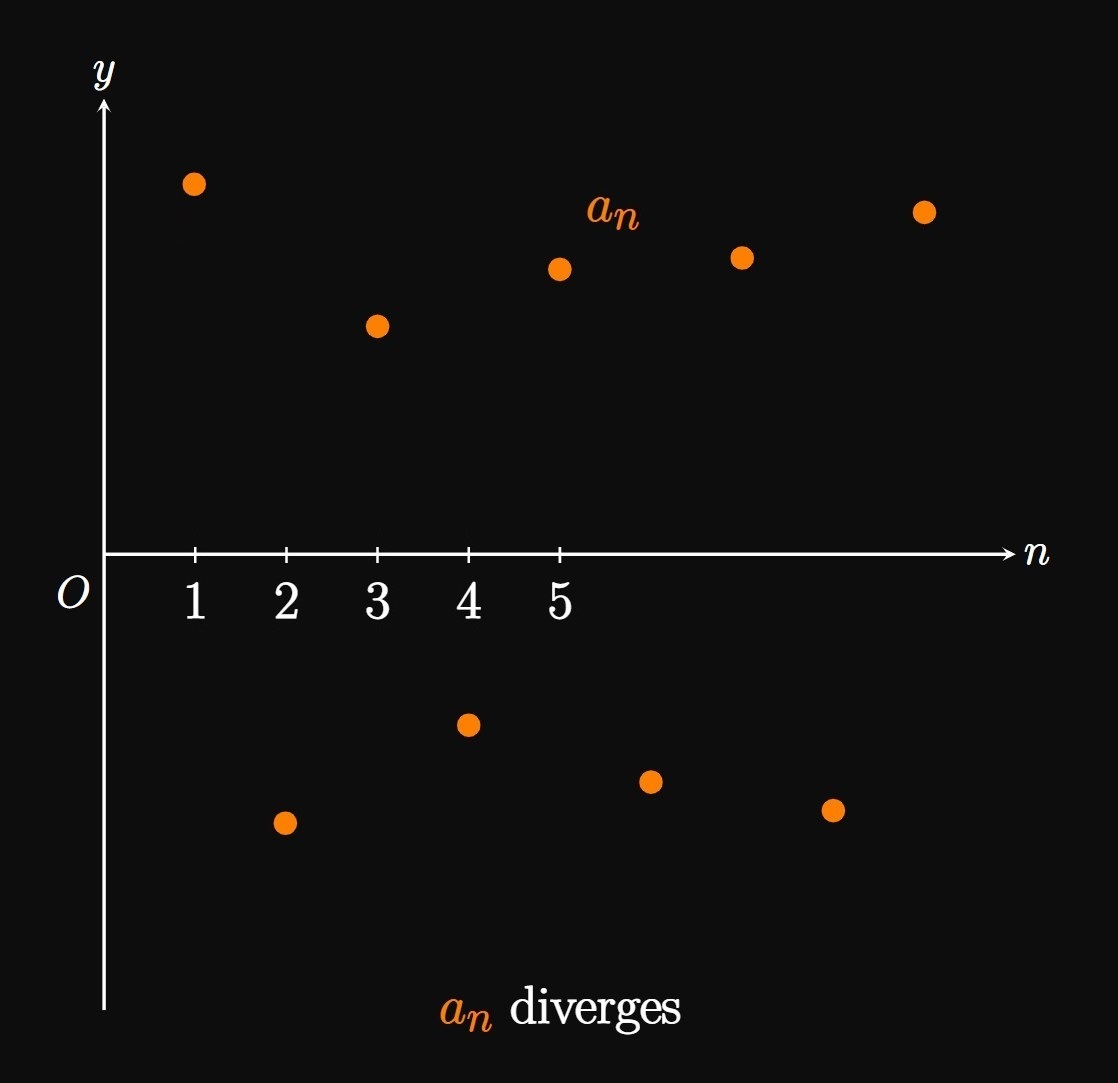

In calculus we study functions of a real variable, whereas sequences are defined by the discrete integer \(n.\) But it turns out that sequences have a deep connection to functions of a real variable. As we increase \(n,\) the terms of the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) could approach some number \(L,\) but they could also fail to settle to any final value. We communicate this idea by taking the limit of \(a_n\) as \(n \to \infty.\) But how do we find the limit of an expression that's defined by nonnegative integers? Let \(f\) be a function of a real variable such that \(f(n) = a_n\) for every nonnegative integer \(n.\) If \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L,\) then it turns out that \[\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n = L \pd\] Simply put, we find the limit of a sequence similarly to how we find the limit of a function. A sequence \(\{a_n\}\) converges to \(L\) if \(\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n = L.\) Then we can make the terms of \(\{a_n\}\) as close to \(L\) as we please by making \(n\) sufficiently large (Figure 1A). Conversely, if \(\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n\) does not exist, then \(\{a_n\}\) diverges—meaning the terms of \(\{a_n\}\) do not approach any final value as \(n \to \infty\) (Figure 1B).

For example, the sequence defined by \(a_n = 1/n\) converges to \(0\) because \[\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n = \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{1}{n} = 0 \pd\] For \(n \geq 1,\) the terms of \(\{a_n\}\) are \[\left\{1, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \frac{1}{4}, \frac{1}{5}, \dots \right\} \cma\] and we observe that each term gets closer to \(0\) as \(n \to \infty.\)

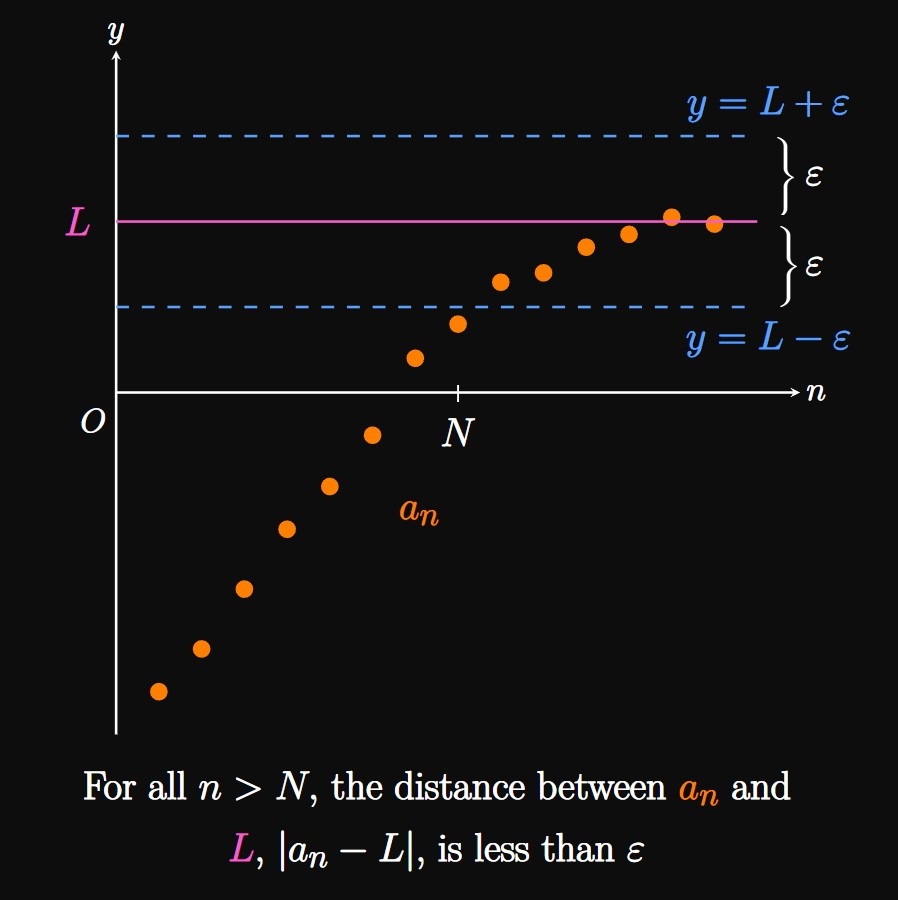

Formally, a sequence \(\{a_n\}\) converges to \(L\) if and only if, for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a nonnegative integer \(N\) exists such that \[\abs{a_n - L} \lt \varepsilon \for n \gt N \pd\] This statement asserts that for \(n \gt N,\) \(a_n\) must not differ from \(L\) by more than \(\varepsilon.\) The value of \(\varepsilon\) can be made smaller as \(N\) is increased. Figure 2 depicts a graphical relationship: the distance between \(L\) and \(a_n\) is \(\abs{a_n - L},\) which is bounded by \(\varepsilon\) and shrinks as \(n \to \infty.\)

Fibonacci Sequence In the 13th century, the Italian mathematician Fibonacci developed a sequence to model an ideal breeding pattern in rabbits: Suppose that two rabbits are left in a field; each rabbit pair mates at the end of the first month and gives birth to another rabbit pair at the end of the second month. Assume that all the rabbits are reproductive and never die. At the end of the first month, the first pair mates but remains in gestation, so the number of rabbit pairs remains at \(1.\) But at the end of the second month, the first pair finally gives birth to another pair of rabbits—giving us \(2\) rabbit pairs. Likewise, at the end of the third month, the original pair produces another pair, but the second pair remains in its gestation period; we therefore have \(3\) rabbit pairs. And at the end of the fourth month, the first and second rabbit pair have each given birth to a new rabbit pair, but the third rabbit pair has not yet finished gestation—leaving us with \(5\) rabbit pairs. So the number of rabbit pairs after \(n\) months is, starting from \(n = 1,\) modeled by the sequence \[\{1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, \dots\} \pd\] Remarkably, each term is the sum of the previous two terms. This surprising pattern is called the Fibonacci Sequence, which we can write recursively as \begin{equation} f_1 = 1 \cmaa f_2 = 1 \cmaa f_n = f_{n - 1} + f_{n - 2} \cmaa n \geq 3 \pd \label{eq:fib-sequence} \end{equation} The Fibonacci sequence is divergent because \(f_n \to \infty\) as \(n \to \infty.\) This result is expected; the number of rabbit pairs should increase indefinitely as increasingly many rabbits reproduce.

The Limit Laws can be applied to the limits of sequences as \(n \to \infty.\) We can also use the Squeeze Theorem for Sequences to prove the convergence of a sequence that is bounded by two other convergent sequences, each of which has the same limit.

Describing Sequences

Let's define a set of descriptions to communicate the characteristics of sequences. In general, we can describe a sequence using three properties—boundedness, increasing or decreasing, and monotonicity.

For example, the sequence \[\{2n + 1\} \subsuper{0}{\infty} = \{1, 3, 5, 7, 9, \dots\}\] is increasing, and therefore monotonic, for \(n \geq 0.\) Conversely, the sequence \(\{0, 0, 0, 0, 0, \dots\}\) is monotonic but is neither increasing nor decreasing. Lastly, the sequence \[\parbrace{(-1)^n + 5} \subsuper{1}{\infty} = \{4, 6, 4, 6, 4, \dots\}\] isn't monotonic because its terms alternate between \(4\) and \(6,\) and the sequence is neither increasing nor decreasing. The former two sequences are examples of bounded sequences, which we define as follows.

- bounded above if a number \(M\) exists such that \(a_n \leq M.\)

- bounded below if a number \(m\) exists such that \(m \leq a_n.\)

- bounded if numbers \(m\) and \(M\) exist such that \(m \leq a_n \leq M.\)

We can solve this problem using two methods—one by manipulating inequalities and the other by comparing the sequence to a function.

Method 1 The sequence is increasing if and only if, for all nonnegative \(n,\) \[ \ba \frac{3(n + 1)}{1 + 4(n + 1)} \gt \frac{3n}{1 + 4n} \pd \ea \] Manipulating the inequality, we see \[ \ba \frac{3n + 3}{4n + 5} &\gt \frac{3n}{1 + 4n} \nl (3n + 3)(1 + 4n) &\gt 3n (4n + 5) \nl 12n^2 + 15n + 3 &\gt 12n^2 + 15n \nl 3 &\gt 0 \pd \ea \] So this inequality is satisfied for all \(n.\)

Method 2 Let's compare the sequence to the function \(f(x) = 3x/(1 + 4x).\) The sequence and the function \(f\) increase together; we therefore show \(f'(x) \gt 0.\) Differentiating gives \[f'(x) = \frac{3(1 + 4x) - 3x (4)}{(1 + 4x)^2} = \frac{3}{(1 + 4x)^2} \cma\] which is positive for all \(x.\) Hence, the sequence is also increasing for all nonnegative \(n.\)

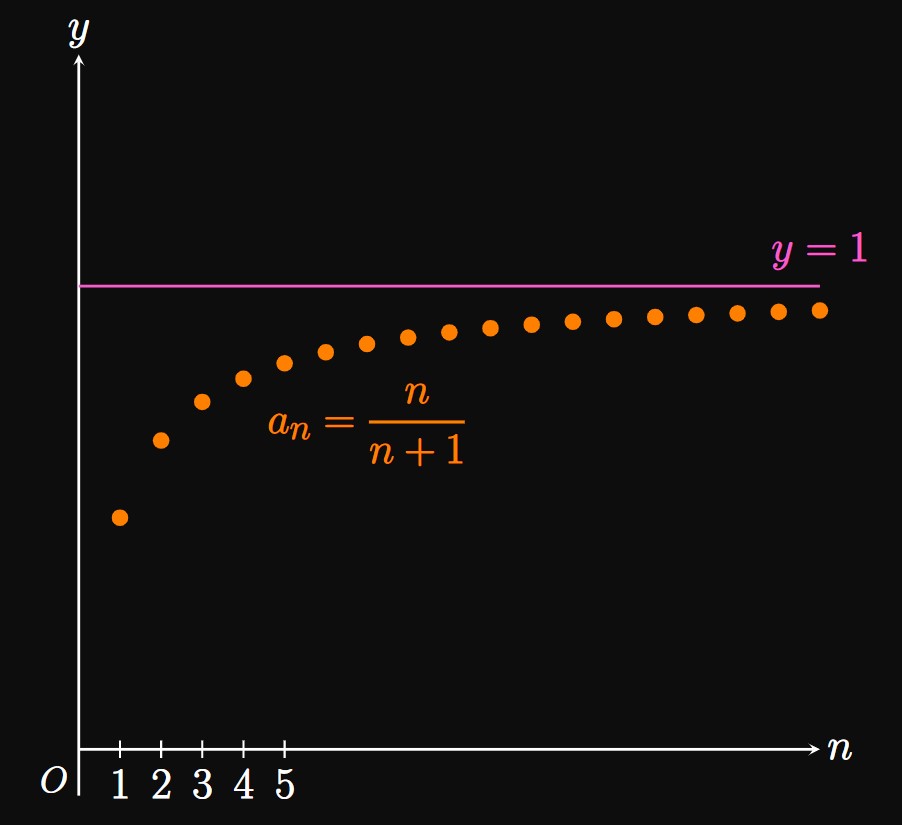

As shown by Example 7,

the terms of \(n/(n + 1)\)

continually grow toward \(1,\) a number that bounds the sequence,

so \(\{n/(n + 1)\}\) converges.

Yet in Example 4

the divergent sequence \(\{(-1)^n\}\) is bounded (between \(-1\) and

PROOF Let's first prove the Monotonic Sequence Theorem for a nondecreasing sequence \(\{a_n\}.\) Since the sequence is bounded, an upper bound \(M\) exists such that \[a_1 \leq a_2 \leq a_3 \leq \dots \leq a_n \leq M \pd\] By the Completeness Axiom, any nonempty set of real numbers that is bounded above has a least upper bound \(L.\) So we see \[a_1 \leq a_2 \leq a_3 \leq \dots \leq a_n \leq L \pd\] For \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) we have \(L - \varepsilon \lt L.\) But since \(L\) is the least upper bound to \(\{a_n\},\) the expression \(L - \varepsilon\) is not an upper bound to the sequence. Thus, there exists some index \(N\) such that \(a_N \gt L - \varepsilon.\) Because the terms are nondecreasing, we have \(a_N \leq a_n\) for \(n \gt N.\) We therefore conclude, for all \(n \gt N,\) \[ L - \varepsilon \lt a_N \leq a_n \leq L \lt L + \varepsilon \pd \] So we see \[L - \varepsilon \lt a_n \lt L + \varepsilon \iffArrow \abs{a_n - L} \lt \varepsilon \pd \] By the definition of a convergent sequence, \(\{a_n\}\) converges. The proof for a nonincreasing sequence is similar. \[\qedproof\]

It is a good idea to write out a few terms to observe the sequence's behavior, as follows: \[ \baat{2} a_2 &= \tfrac{1}{2} a_1 + 4 = 5 &\lspace a_3 &= \tfrac{1}{2} a_2 + 4 = 6.5 \nl a_4 &= 7.25 &\lspace a_5 &= 7.625 \nl a_6 &= 7.8125 &\lspace a_7 &= 7.90625 \nl a_8 &= 7.953125 &\lspace a_9 &= 7.9765625 \pd \eaat \] It appears that the sequence is increasing and bounded above by \(8.\) Now let's verify this guess.

Monotonicity and Boundedness

Let's prove mathematically that the sequence is increasing.

We use a Proof by Induction to prove that \(a_{n + 1} \gt a_n\)

for all \(n \geq 1.\)

First observe that \(a_2 \gt a_1,\)

so the inequality is true for \(n = 1.\)

Assuming that \(a_{n + 1} \gt a_n\) is true for \(n = k,\) where \(k \geq 1,\) we have

\[

\ba

a_{k + 1} &\gt a_k \nl

\tfrac{1}{2} a_{k + 1} &\gt \tfrac{1}{2} a_k \nl

\tfrac{1}{2} a_{k + 1} + 4 &\gt \tfrac{1}{2} a_k + 4 \nl

a_{k + 2} &\gt a_{k + 1} \pd

\ea

\]

Hence, \(a_{n + 1} \gt a_n\) is true for \(n = k + 1.\)

Thus, by mathematical induction, the sequence \(a_n\) is increasing for all \(n \geq 1.\)

Let's now show that the sequence is bounded:

Since the sequence is increasing for \(n \geq 1,\) it has a lower bound of \(m = a_1 = 2.\)

We know \(a_1 \lt 8,\) so let's prove that \(a_n \lt 8\) for all \(n.\)

Assuming that \(a_n \lt 8\) is true for \(n = k\) (where

Limit of the Sequence Given that the sequence converges, both \(a_{n + 1}\) and \(a_n\) approach the same value \(L\) as \(n \to \infty.\) Our analysis has proved that \(\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n\) exists, but we don't know what it equals. Using the recursive relationship, we see \[ \ba \lim_{n \to \infty} a_{n + 1} &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \par{\tfrac{1}{2} a_n + 4} \nl L &= \tfrac{1}{2} L + 4 \nl L &= 8 \pd \ea \] So the limit of the sequence is \(\boxed{8},\) as we expect.

Defining a Sequence

A sequence is a list of numbers written in a definite order:

\[\{a_1, a_2, a_3, \dots, a_N\} \pd\]

We call \(a_1\) the first term, \(a_2\) the second term,

and \(a_N\) the

Limits of Sequences

As \(n \to \infty,\) the terms of \(a_n\) may tend to some fixed value \(L\)—that is,

\(\lim_{n \to \infty} a_n = L.\)

If so, then the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is said to converge and have

a limit of \(L.\)

Otherwise, the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is said to diverge.

A famous example of a divergent sequence is the Fibonacci Sequence,

in which each term is the sum of the two preceding terms,

as defined recursively by

\begin{equation}

f_1 = 1 \cmaa f_2 = 1 \cmaa f_n = f_{n - 1} + f_{n - 2} \cmaa n \geq 3 \pd \eqlabel{eq:fib-sequence}

\end{equation}

When expanded, the sequence is

\[\{1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, \dots\} \pd\]

Formally, a sequence \(\{a_n\}\) converges to \(L\)

if and only if, for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a nonnegative integer \(N\) exists such that

\[\abs{a_n - L} \lt \varepsilon \for n \gt N \pd\]

We compute the limit of a sequence similarly to how we compute the limit of a function

of a real variable:

If \(f(x)\) is a function (of a real variable

Describing Sequences A sequence \(\{a_n\}\) can be described using three properties—boundedness, monotonicity, and increasing or decreasing. Let \(N\) be a nonnegative integer. Then the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is increasing if \(a_n \lt a_{n + 1}\) for all \(n \geq N.\) It is decreasing if \(a_n \gt a_{n + 1}\) for all \(n \geq N.\) The sequence is monotonic if its terms are nondecreasing or nonincreasing—that is, if \(a_n \leq a_{n + 1}\) or \(a_n \geq a_{n + 1}\) for \(n \geq N.\) Hence, every increasing or decreasing sequence is monotonic. For \(n \geq N,\) the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is

- bounded above if a number \(M\) exists such that \(a_n \leq M.\)

- bounded below if a number \(m\) exists such that \(m \leq a_n.\)

- bounded if numbers \(m\) and \(M\) exist such that \(m \leq a_n \leq M.\)

The Monotonic Sequence Theorem asserts that a bounded, monotonic sequence is convergent.