0.9: Exponents and Logarithms

Many operations in mathematics rely on exponents and logarithms. Understanding these topics is crucial for engaging with calculus. In this section we review the following topics:

Exponents and Exponential Functions

In an exponential function, the exponent is a variable. An example is \(f(x) = 2^x,\) whereas \(g(x) = x^2\) is a power function since the base is a variable. In general, an exponential function is of the form \begin{equation} f(x) = b^x \label{eq:def-exp} \end{equation} where \(b\) is a positive constant with \(b \ne 1.\)

What does the power of an exponential function really mean?

Let's take \(n\) to be any positive integer.

In \(\eqref{eq:def-exp}\) the simplest case is \(x = n,\)

which represents repeated multiplication:

\[b^n = \underbrace{b \cdot b \cdot \, \cdots \, \cdot b}_{n \text{ factors}} \pd\]

But if \(x = -n\) then

\[b^{-n} = \frac{1}{b^n} = \frac{1}{\underbrace{b \cdot b \cdot \, \cdots \, \cdot b}_{n \text{ factors}}} \pd\]

Recall that any nonzero number raised to the power of \(0\)

equals \(1;\) that is, \(b^0 = 1.\)

If \(x\) is a rational number, \(x = p/q,\) where \(p\) and \(q\) are positive integers,

then

\[b^x = b^{p/q} = \sqrt[q]{b^p} \pd\]

To evaluate \(\sqrt[q]{b^p},\)

we first raise \(b\) to the power of \(p\) and then take the

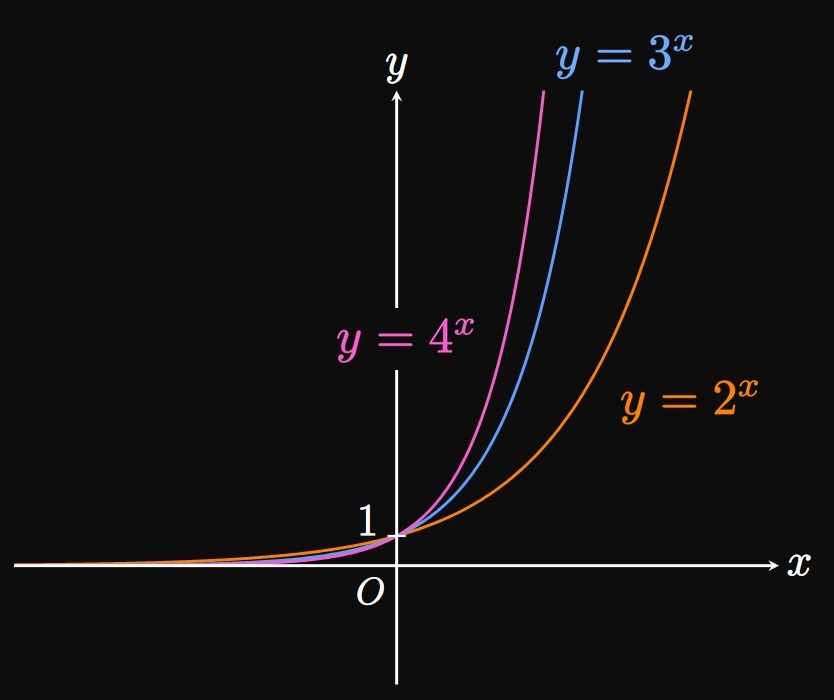

The preceding interpretations enable us to sketch the graphs of exponential functions. Figure 1A shows the graphs of \(y = 2^x,\) \(y = 3^x,\) and \(y = 4^x.\) Exponential functions with larger bases grow more rapidly. In addition, since \((1/b)^x\) \(= b^{-x},\) the graph of \(y = (1/b)^x\) is the reflection of \(y = b^x\) across the \(y\)-axis: Figure 1B shows the graphs of \(y = (1/2)^x,\) \(y = (1/3)^x,\) and \(y = (1/4)^x.\) The graph of \(y = (1/b)^x,\) \(b \gt 1,\) is therefore said to exhibit exponential decay. Note that all exponential graphs have a \(y\)-intercept of \((0, 1)\) because \(b^0 = 1.\) These functions also have a domain of \((-\infty, \infty)\) and a range of \((0, \infty).\)

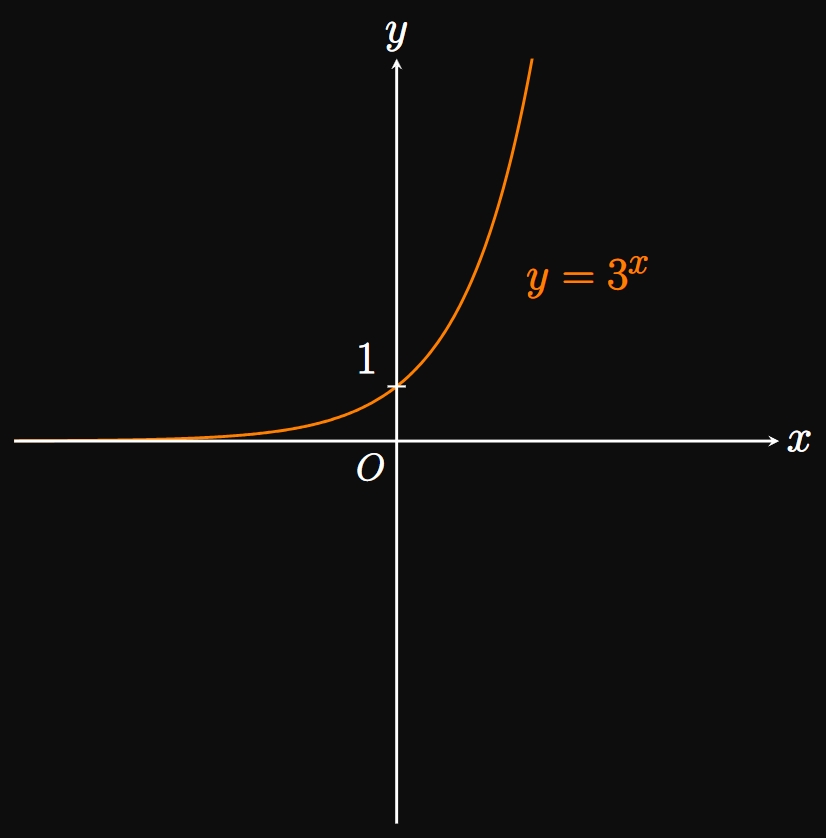

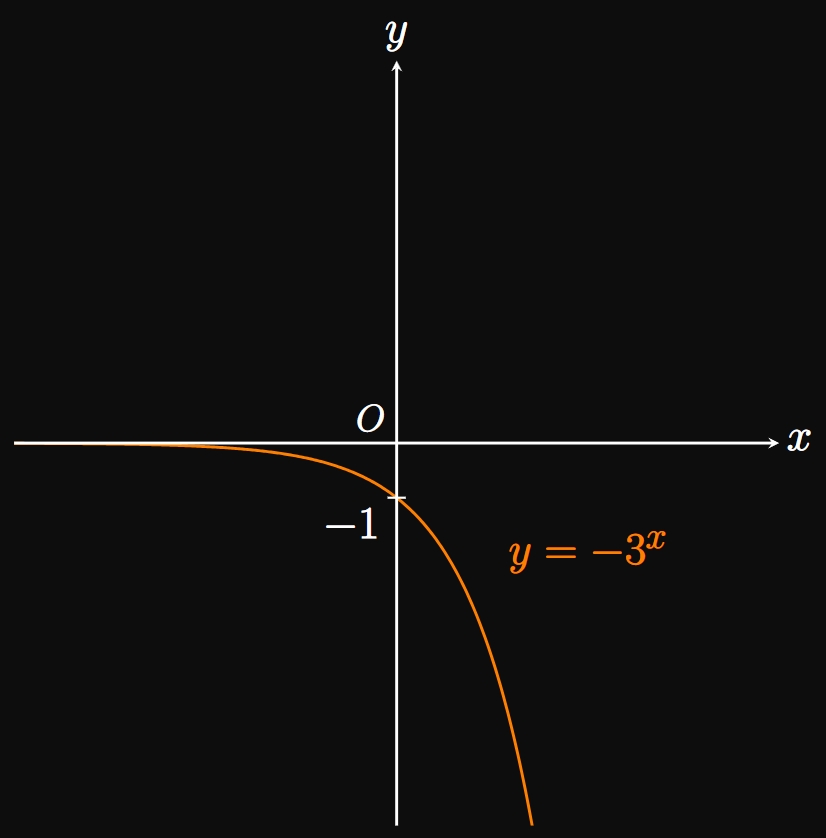

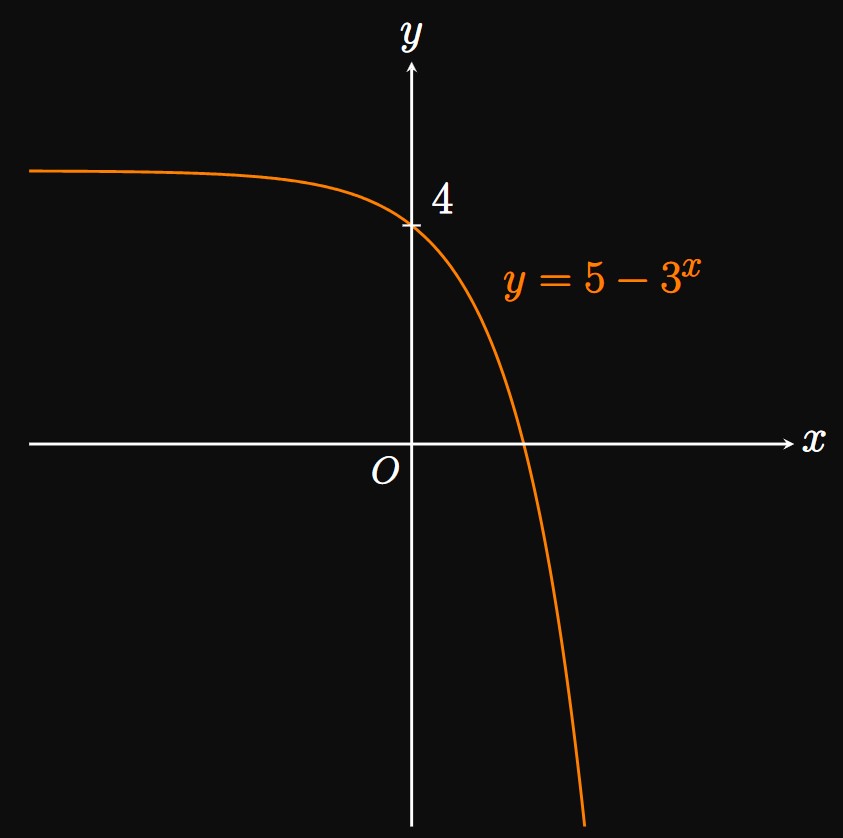

First we sketch the parent graph of \(y = 3^x,\) as shown in Figure 2A. Then we reflect the graph across the \(x\)-axis (Figure 2B) and finally translate it \(5\) units upward (Figure 3). The domain is \((-\infty, \infty),\) and the range is \((-\infty, 5).\)

Next we discuss rules with exponents, shown below. Although we omit the proofs of these properties, we encourage you to experiment with numbers and verify that they are true.

Logarithms and Logarithmic Functions

If \(b \gt 0\) and \(b \ne 1,\) then the exponential function \(f(x) = b^x\) is either increasing or decreasing. Accordingly, the graph is one-to-one; it passes the Horizontal Line Test. Then \(f\) has an inverse function called the logarithmic function, \(\inv f(x) = \log_b x.\) Exponents and logarithms therefore share the following bidirectional relationship: \begin{equation} y = b^x \iffArrow x = \log_b y \pd \label{eq:exp-log} \end{equation} So a logarithmic function of base \(b,\) when given a number \(y,\) outputs the power to which \(b\) must be raised to give \(y.\) For example, \(2^3 = 8\) implies \(\log_2 8 = 3\) because \(2\) must be raised to the power of \(3\) to become \(8.\) Likewise, since \(b^1 = b\) and \(b^0 = 1,\) it follows that \begin{equation} \log_b b = 1 \and \log_b 1 = 0 \pd \label{eq:log-1} \end{equation}

Special Logarithms The common logarithm is a logarithm of base \(10.\) In this text, the common logarithm is written simply as \(\log\) with no base, so \(\log x\) strictly means \(\log_{10} x.\) For example, \(\log 100 = 2\) since \(10^2 = 100.\) Ironically, in calculus the common logarithm is used far less than the natural logarithm, whose base is Euler's number—the irrational number \(e \approx 2.718.\) The natural logarithm is denoted as \(\ln;\) for example, \(\ln \par{e^2} = 2\) because \(2\) is the power to which \(e\) must be raised to attain \(e^2.\) Euler's number satisfies many beautiful mathematical properties, and we will formally define it in Chapter 2.

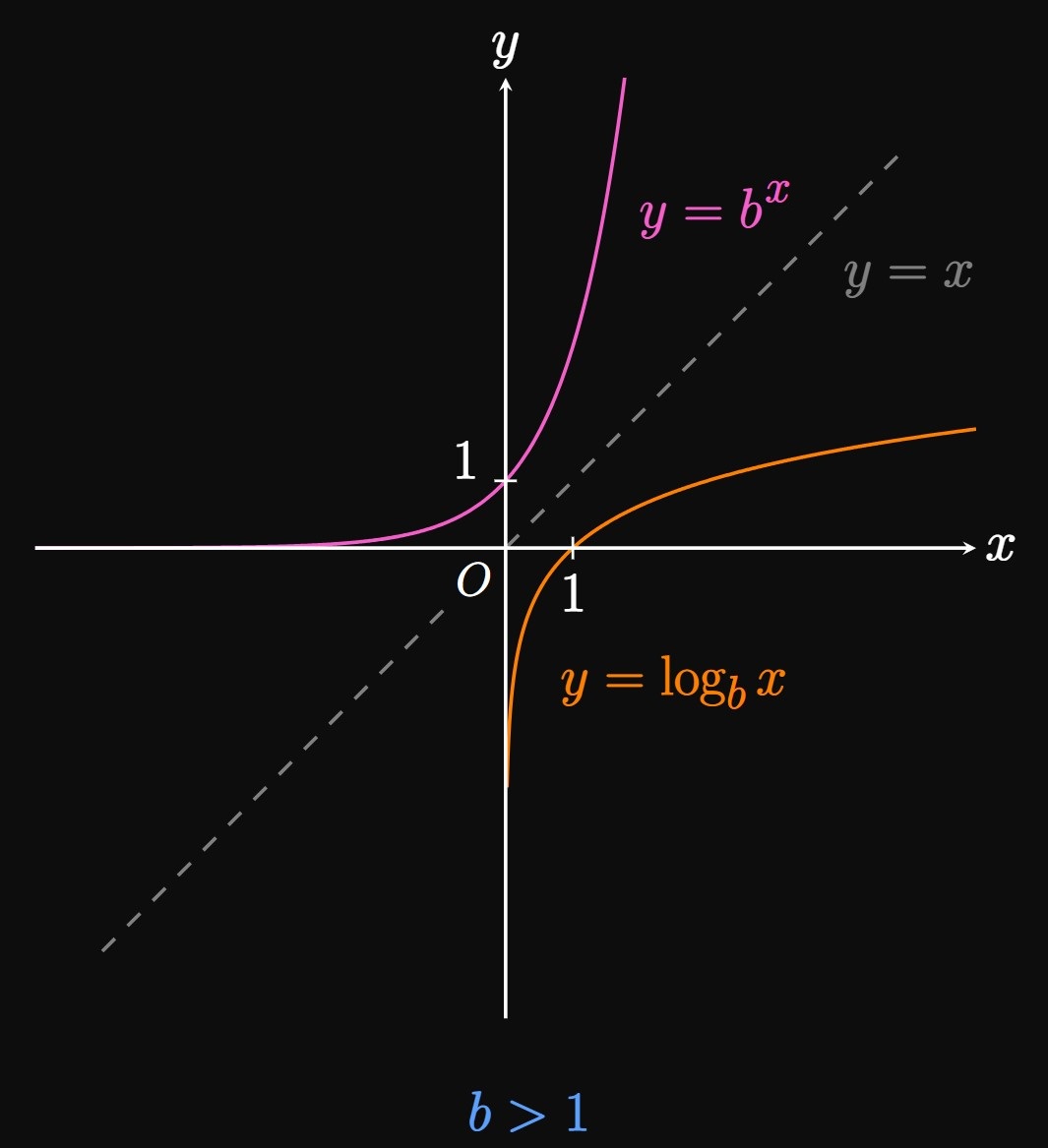

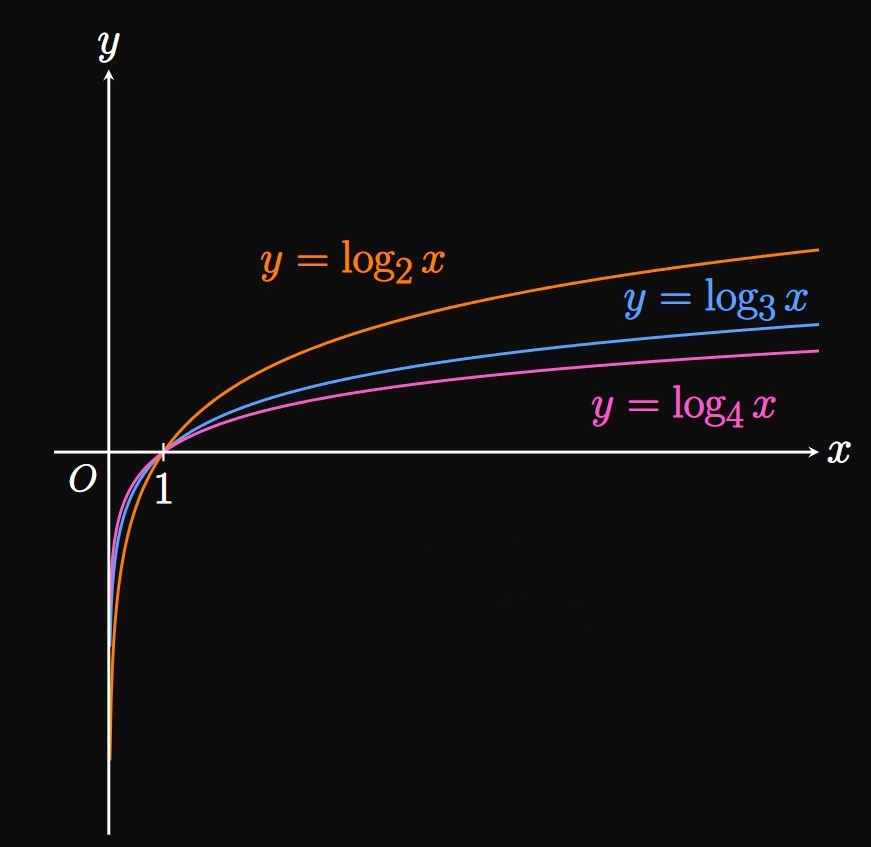

Because the exponential function and the logarithmic function are inverses of each other, their graphs are reflections of each other across the line \(y = x.\) Because \(y = b^x\) passes through \((0, 1),\) \(y = \log_b x\) passes through \((1, 0).\) Most useful logarithms have bases greater than \(1,\) so let's consider \(b \gt 1.\) Then the graph of \(y = \log_b x\) is shown by Figure 4. Whereas \(y = b^x\) increases rapidly, \(y = \log_b x\) grows painfully slowly. Examine that \(\log 100\) \(= 2,\) \(\log 1000\) \(= 3,\) and \(\log 10000\) \(= 4.\) Figure 5 shows the graphs of \(y = \log_2 x,\) \(y = \log_3 x,\) and \(y = \log_4 x.\) All of these graphs have an \(x\)-intercept of \((1, 0),\) a domain of \((0, \infty),\) and a range of \((-\infty, \infty).\)

- \(\log_3 81\)

- \(\log_4 2\)

- \(\log_8 \frac{1}{64}\)

- Since \(3^4 = 81,\) the logarithm gives the power: \[\log_3 81 = \boxed 4\]

- Taking the square root of \(4\)—that is, raising \(4\) to the power of \(1/2\)—gives \(2.\) Accordingly, \[\log_4 2 = \boxed{\tfrac{1}{2}}\]

- Note that \(8^2 = 64,\) so \(8^{-2} = 1/64.\) The logarithm equals the power: \[\log_8 \tfrac{1}{64} = \boxed{-2}\]

In Example 5, as we solve \(\log_4 x = 3,\) another perspective is to exponentiate both sides: \[ \ba \cancel{4}^{\cancel{\log_4} x} &= 4^3 \nl x &= 4^3 = 64 \pd \ea \] In general, for \(x \gt 0,\) \begin{equation} b^{\log_b x} = x \pd \label{eq:exp-log-cancel} \end{equation} Thus, by exponentiating both sides of an equation, we can strip logarithms.

The properties of logarithms are shown below, and the proofs for these rules are left as exercises.

In words, logarithms enable us to split a product into a sum [by

Change of Base Formula

Not all logarithms can be evaluated by hand,

so a calculator may be necessary.

But many scientific calculators only have one base for the logarithmic function,

either log or ln.

We therefore need a formula that enables us to convert between logarithmic bases.

Letting \(y = \log_b x,\) where \(b\) is a positive number and \(b \ne 1,\)

we have \(x = b^y\) by \(\eqref{eq:exp-log}.\)

On both sides we take the logarithm of any base \(c\) \((c \gt 0\) and \(c \ne 1)\) and use \(\eqref{eq:log-p} \col\)

\begin{align}

\log_c x &= \log_c \par{b^y} \nonum \nl

\log_c x &= y \log_c b \nonum \nl

y &= \frac{\log_c x}{\log_c b} \nonum \nl

\log_b x &= \frac{\log_c x}{\log_c b} \pd \label{eq:log-change-base}

\end{align}

This form enables us to compute logarithms on scientific calculators that offer only one base;

as an example,

\[\log_9 7 = \frac{\log 7}{\log 9} = \frac{\ln 7}{\ln 9} \approx 0.886 \pd\]

Exponents and Exponential Functions In an exponential function, the power is a variable: \begin{equation} f(x) = b^x \eqlabel{eq:def-exp} \end{equation} where \(b\) is a positive constant with \(b \ne 1.\) If \(b \gt 1,\) then the graph of \(y = b^x\) exhibits exponential growth, growing rapidly. But the graph of \(y = (1/b)^x\) undergoes exponential decay and so decreases. An exponential graph has a \(y\)-intercept of \((0, 1),\) a domain of \((-\infty, \infty),\) and a range of \((0, \infty).\) Let \(a\) and \(b\) be positive numbers, and let \(m\) and \(n\) be any real numbers. Then the exponent laws are as follows: \begin{align} a^{m + n} &= a^m \, a^n \cma \eqlabel{eq:exp-law-add} \nl a^{m - n} &= \frac{a^m}{a^n} \cma \eqlabel{eq:exp-law-minus} \nl \par{a^{m}}^n &= a^{mn} \cma \eqlabel{eq:exp-law-mn} \nl \par{ab}^n &= a^n \, b^n \pd \eqlabel{eq:exp-law-a-b} \end{align}

Logarithms and Logarithmic Functions

The logarithmic function \(\log_b x\)

is the inverse function of the exponential function \(b^x.\)

Exponents and logarithms therefore have the following bidirectional relationship:

\begin{equation}

y = b^x \iffArrow x = \log_b y \pd \eqlabel{eq:exp-log}

\end{equation}

In words, the logarithm gives the power \(x\) to which \(b\) must be raised to produce \(y.\)

Given that \(b^1 = b\) and \(b^0 = 1,\) examples of logarithm applications are

\begin{equation}

\log_b b = 1 \and \log_b 1 = 0 \pd \eqlabel{eq:log-1}

\end{equation}

In addition, exponentiating a logarithmic expression cancels

the logarithm:

\begin{equation}

b^{\log_b x} = x \eqlabel{eq:exp-log-cancel}

\end{equation}

for \(x \gt 0.\)

The graph of \(y = \log_b x,\) \(b \gt 1,\)

grows very slowly;

and it has an \(x\)-intercept of \((1, 0),\)

a domain of \((0, \infty),\)

and a range of \((-\infty, \infty).\)

The common logarithm is a logarithm of base \(10;\)

in this text, \(\log x\) exclusively means \(\log_{10} x.\)

Yet calculus often uses the natural logarithm,

whose base is Euler's number, the irrational number \(e \approx 2.718.\)

The notation of the natural logarithm is \(\ln.\)

Let \(b\) be a positive number with \(b \ne 1.\)

If \(x\) and \(y\) are positive numbers and \(p\) is any real number,

then the logarithm laws are as follows:

\begin{align}

\log_b(xy) &= \log_b x + \log_b y \cma \eqlabel{eq:log-add} \nl

\log_b \par{\frac{x}{y}} &= \log_b x - \log_b y \cma \eqlabel{eq:log-minus} \nl

\log_b \par{x^p} &= p \log_b x \pd \eqlabel{eq:log-p}

\end{align}

Conversely, suppose that \(b\) and \(c\) are positive numbers such that \(b \ne 1\) and \(c \ne 1.\)

Then the Change of Base Formula for Logarithms gives

\begin{equation}

\log_b x = \frac{\log_c x}{\log_c b} \pd \eqlabel{eq:log-change-base}

\end{equation}

This formula enables us to compute logarithms with custom bases

on devices that only offer one logarithm base.