10.7: Power Series

In this section, we learn to express functions as power series, which are similar to polynomials with infinitely many terms. Power series have many applications. We use them to integrate functions that don't have elementary antiderivatives, and they serve a key role in approximating physical phenomena. This section covers the following topics:

- Power Series, Radius of Convergence, and Interval of Convergence

- Geometric Power Series

- Differentiating and Integrating Power Series

Power Series, Radius of Convergence, and Interval of Convergence

A power series resembles a polynomial with an infinite number of terms—an infinite series of powers. The general form of a power series is \begin{equation} \sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n = c_0 + c_1 (x - a) + c_2 (x - a)^2 + \cdots \pd \label{eq:power-series-form} \end{equation} The quantity \(c_n\) is a coefficient in each term, and \(x = a\) is called the center of the power series. For any value of \(x,\) \(\eqref{eq:power-series-form}\) becomes a sum of numbers that either converges or diverges. The values of \(x\) for which \(\eqref{eq:power-series-form}\) becomes a convergent series make up the interval of convergence. The center value of the interval of convergence is \(a,\) and the interval's endpoints each extend a value \(R\)—called the radius of convergence—in each direction of \(a.\) Hence, if the power series in \(\eqref{eq:power-series-form}\) has a radius of convergence \(R,\) then the general form for its interval of convergence is \((a - R, a + R).\) We first write this preliminary interval and then determine whether the power series converges at each endpoint. For example, the following possibilities exist:

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) converges at both \(x = a - R\) and \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \([a - R, a + R].\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) converges at \(x = a - R\) and diverges at \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \([a - R, a + R).\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) diverges at \(x = a - R\) and converges at \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \((a - R, a + R].\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) diverges at both \(x = a - R\) and \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \((a - R, a + R).\)

There are two special cases: If \(R = 0,\) then the power series \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) only converges at \(x = a.\) If \(R = \infty,\) then the power series converges for all \(x \in \RR.\)

Let \(a_n = (x - 2)^n/n.\) The key idea is to write a condition that assumes \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) is convergent, and then solve for \(x\) that satisfies the condition. We do so using the Ratio Test (see Section 10.6), which states that \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) converges if \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{a_{n + 1}/a_n} \lt 1.\) The values of \(x\) that satisfy this inequality make up the interval of convergence.

Radius of Convergence Note that \(a_{n + 1} = (x - 2)^{n + 1}/(n + 1).\) We have \[ \ba L &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{a_{n + 1}}{a_n}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\dfrac{\dfrac{(x - 2)^{n + 1 \strut}}{n + 1}}{\dfrac{(x - 2)^n \strut}{n}}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{\cancel{(x - 2)^n} (x - 2)}{n + 1} \cdot \frac{n}{\cancel{(x - 2)^n}}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{(x - 2) \, n}{n + 1}} \nl &= \abs{x - 2} \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{n}{n + 1} \nl &= \abs{x - 2} \pd \ea \] The series \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) converges if \(L \lt 1,\) that is, if \(\abs{x - 2} \lt 1.\) Solving this inequality shows \[-1 \lt x - 2 \lt 1 \iffArrow 1 \lt x \lt 3 \pd\] The radius of convergence is \(\boxed{R = 1}\) because the endpoints of \((1, 3)\) extend \(1\) in either direction of the center of the power series, \(2.\)

Interval of Convergence The preliminary interval of convergence is \(1 \lt x \lt 3.\) We now test each endpoint: Substituting \(x = 1\) into \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) gives \[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(1 - 2)^n}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{n} \cma \] which converges by the Alternating Series Test because \(1/n\) is decreasing to \(0\) as \(n \to \infty.\) But at \(x = 3\) the series becomes \[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(3 - 2)^n}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(1)^n}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} \cma \] which diverges because it is the Harmonic series. Therefore, we include \(x = 1\) and exclude \(x = 3\) in the interval of convergence, attaining \[\boxed{1 \leq x \lt 3}\]

Let \(a_n = x^{2n}/n! \,.\) Note that \(a_{n + 1} = x^{2n + 2}/(n + 1)! \, .\) We see \[ \ba L &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{a_{n + 1}}{a_n}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{x^{2n + 2}}{(n + 1)!} \cdot \frac{n!}{x^{2n}}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{x^{2n} \, x^2}{(n + 1) \, n!} \cdot \frac{n!}{x^{2n}}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{x^2}{n + 1}} \nl &= \abs{x^2} \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{1}{n + 1} \nl &= 0 \pd \ea \] Thus, \(L = 0 \lt 1\) is always true regardless of the value of \(x.\) Therefore, the power series \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) converges for any value of \(x.\) So the interval of convergence is \[\boxed{-\infty \lt x \lt \infty}\] and the radius of convergence is \(\boxed{R = \infty}.\)

We call \(a_n = (-1)^n \, x^{3n}/n.\) The series \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) converges if \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{a_{n + 1}/a_n} \lt 1,\) according to the Ratio Test. We then solve for \(x\) that satisfies this condition. Note that \[a_{n + 1} = \frac{(-1)^{n + 1} \, x^{3(n + 1)}}{n + 1} = \frac{(-1)^{n + 1} \, x^{3n} \cdot x^3}{n + 1} \pd\]

Radius of Convergence We set up the limit \[ \ba L &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{a_{n + 1}}{a_n}} \nl &= \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{(-1)^{n + 1} \, x^{3n} \cdot x^3}{n + 1} \cdot \frac{n}{(-1)^n \, x^{3n}}} \nl &= \abs{x^3} \lim_{n \to \infty} \abs{\frac{n}{n + 1}} \nl &= \abs{x^3} \pd \ea \] The series converges if \(L \lt 1\)—that is, for \[\abs{x^3} \lt 1 \iffArrow \abs{x} \lt 1 \iffArrow -1 \lt x \lt 1 \pd\] This is our preliminary interval of convergence of \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n.\) The radius of convergence is \(\boxed{R = 1}.\)

Interval of Convergence We next evaluate \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) at the endpoints of \(-1 \lt x \lt 1.\) Substituting \(x = -1\) gives \[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n (-1)^{3n}}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{4n}}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} \cma\] which diverges because it is the Harmonic series. At \(x = 1\) the series becomes \[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n (1)^{3n}}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{n} \cma\] which converges by the Alternating Series Test because \(\lim_{n \to \infty} (1/n) = 0\) and \(1/n\) is decreasing for \(n \geq 1.\) Thus, we exclude \(x = -1\) and include \(x = 1,\) so the interval of convergence is \[\boxed{-1 \lt x \leq 1}\]

Geometric Power Series

In Section 10.2 we asserted that a convergent infinite geometric series takes the form

\[1 + r + r^2 + r^3 + \cdots = \frac{1}{1 - r} \cma\]

where \(|r| \lt 1.\)

We now reverse this perspective

by using an infinite sum to define a rational function.

If \(|x| \lt 1,\) then we express \(1/(1 - x)\) as the following geometric power series:

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{1 - x} = 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + \cdots = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty x^n \pd \label{eq:geo-power-series}

\end{equation}

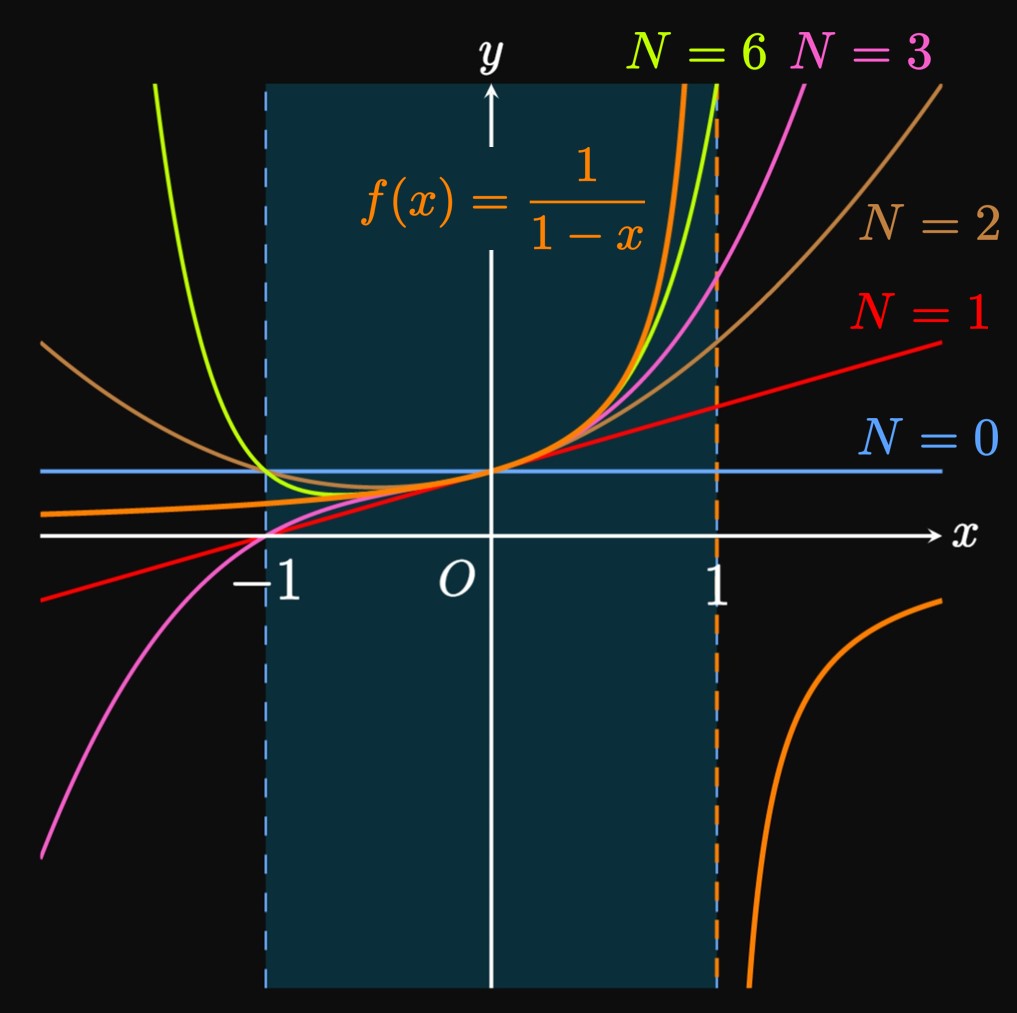

Let's construct a polynomial using only a few terms of this power series; that is,

we plot the graph of \(y = \sum_{i = 0}^N x^i.\)

For \(N = 0\) the polynomial is merely \(y = 1;\)

for \(N = 1\) the polynomial is \(y = 1 + x;\)

for \(N = 2\) the polynomial is \(y = 1 + x + x^2.\)

In Figure 1

polynomials of various degrees \(N\) approximate the graph of \(f(x) = 1/(1 - x).\)

As \(N\) increases—that is, as we use more terms from \(\eqref{eq:geo-power-series}\)—the polynomials better match the graph of \(f.\)

But the polynomials only converge to \(f\) if \(|x| \lt 1,\) that is, if \(-1 \lt x \lt 1.\)

Hence, \((-1, 1)\) is the interval of convergence for the power series \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty x^n.\)

In other words, the series converges—converges to \(f\)—for \(x\) in \((-1, 1)\) but diverges for \(x\) outside this interval.

For example, if \(x = 1/2,\) then \(\eqref{eq:geo-power-series}\) becomes the convergent geometric series

\[1 + \par{\frac{1}{2}} + \par{\frac{1}{2}}^2 + \par{\frac{1}{2}}^3 + \cdots + \par{\frac{1}{2}}^n + \cdots \cma\]

and this series converges to \(f \par{\frac{1}{2}} = 1/\par{1 - \frac{1}{2}}.\)

But if \(x = 2\) (a value outside the interval of convergence of the power series representation for

We obtain many useful power series representations by manipulating \(\eqref{eq:geo-power-series};\) for example, replacing \(x\) with \(2x\) gives \[1 + (2x) + (2x)^2 + (2x)^3 + \cdots + (2x)^n + \cdots = \frac{1}{1 - 2x} \pd\] Likewise, we can derive power series expansions for many rational functions—for example, \(1/(1 + x^2),\) \(1/(1 - x^3),\) and \(x/(2 + x^2)\)—by replacing \(x\) in \(\eqref{eq:geo-power-series}\) with a new common ratio and multiplying the entire series as necessary. The following examples show this strategy.

Interval and Radius of Convergence The series converges if \(|r| \lt 1\)—that is, \[ \ba \abs{-x^2} \lt 1 &\iffArrow \abs{x^2} \lt 1 \nl &\iffArrow \abs{x} \lt 1 \nl &\iffArrow -1 \lt x \lt 1 \pd \ea \] Hence, the interval of convergence is \[\boxed{-1 \lt x \lt 1}\] The radius of convergence is \(\boxed{R = 1}.\)

When constructing a power series, we may want to center the series at \(x = a.\) In these cases, we must find a power series whose terms have the factor \((x - a).\) To construct a geometric power series centered at \(x = a,\) we manipulate the common ratio to have the factor \(r = (x - a),\) as shown by the following example.

We require a power series to be centered at \(x = 2,\) so the terms should contain the factor \((x - 2).\) In the denominator of \(g,\) we subtract \(2\) and add \(2\) to \(x \col\) \[g(x) = \frac{1}{1 - (x - 2 + 2)} = \frac{1}{-1 - (x - 2)} = \frac{-1}{1 - [-(x - 2)]} \pd\] This expression is attained by replacing \(x\) with \(-(x - 2)\) in \(\eqref{eq:geo-power-series},\) so \(g(x)\) represents an infinite geometric series with common ratio \(r = -(x - 2).\) Consequently, \[ \ba \frac{-1}{1 - [-(x - 2)]} &= - \sum_{n = 0}^\infty [-(x - 2)]^n \nl &= -\sum_{n = 0}^\infty (-1)^n (x- 2)^n \nl &= \boxed{\sum_{n = 0}^\infty (-1)^{n + 1} (x - 2)^n} \ea \]

Radius and Interval of Convergence The series converges when \(\abs r \lt 1,\) where \(r = -(x - 2).\) Thus, \(\abs r = \abs{x - 2},\) so we have \[\abs{x - 2} \lt 1 \iffArrow -1 \lt x - 2 \lt 1 \iffArrow 1 \lt x \lt 3 \pd\] Hence, the interval of convergence is \[\boxed{1 \lt x \lt 3}\] and the radius of convergence is \(\boxed{R = 1}.\)

Differentiating and Integrating Power Series

To differentiate or integrate a power series, we differentiate or integrate term by term—just as we do for polynomials. Algebraically, the derivative of a sum is the sum of a derivative, and likewise for integrals. If a power series representation for \(f(x)\) has a radius of convergence of \(R,\) then the power series representations of \(f'(x)\) and \(\int f(x) \di x\) each also have a radius of convergence of \(R.\) The following box lists the results of differentiating and integrating a power series.

When we differentiate or integrate a power series, we must check the endpoints of the interval of convergence. Although the radius of convergence remains the same, the interval of convergence may not be the same.

- Find a power series for \(f'(x).\)

- Function \(g\) satisfies \(f(x) = g'(x)\) and \(g(5) = 1.\) Find a power series representation for \(g(x).\)

- Because the derivative of a sum is the sum of derivatives, we have \[f'(x) = \deriv{}{x} \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(x - 5)^n}{n} = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \deriv{}{x} \parbr{\frac{(x - 5)^n}{n}} \pd\] We differentiate the summation formula, obtaining \[f'(x) = \boxed{\sum_{n = 1}^\infty (x - 5)^{n - 1}}\] We don't need to increment the starting index \(n = 1,\) because the first term of \(f\) is \((x - 5),\) \[f'(x) = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty (x - 5)^n \pd\]

- Since \(f(x) = g'(x),\) we have \(g(x) = \int f(x) \di x.\) Accordingly, we attain \(g\) by integrating the power series for \(f \col\) \[ \ba g(x) &= \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \int \frac{(x - 5)^n}{n} \di x \nl &= C + \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(x - 5)^{n + 1}}{n(n + 1)} \nl &= C + \frac{(x - 5)^2}{1(2)} + \frac{(x - 5)^3}{2(3)} + \frac{(x - 5)^4}{3(4)} + \cdots \pd \ea \] To solve for \(C,\) we substitute \(g(5) = 1\) and note that all the terms except \(C\) are \(0 \col\) \[ \ba g(5) = C + \frac{(5 - 5)^2}{1(2)} + \frac{(5 - 5)^3}{2(3)} + \cdots &= 1 \nl \implies C &= 1 \pd \ea \] Hence, \[g(x) = \boxed{1 + \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{(x - 5)^{n + 1}}{n(n + 1)}}\]

Interval of Convergence; Solving for \(C\) The power series for \(1/(1 + x)\) converges if \(\abs{-x} \lt 1,\) so the radius of convergence is \(R = 1.\) Therefore, the power series for \(f(x) = \ln(1 + x),\) as in \(\eqref{eq:ln(1+x)},\) has a preliminary interval of convergence of \(-1 \lt x \lt 1.\) We exclude \(x = -1\) because \(f(-1) = \ln 0\) is undefined. But at \(x = 1\) \(\eqref{eq:ln(1+x)}\) becomes \[\sum_{n = 0}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{(1)^{n + 1}}{n + 1} = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{n + 1} \cma\] which converges by the Alternating Series Test since \(1/(n + 1)\) is decreasing to \(0.\) Thus, the interval of convergence is \[\boxed{-1 \lt x \leq 1}\] To solve for \(C\) in \(\eqref{eq:ln(1+x)},\) we substitute any value of \(x\) within the interval of convergence—say, \(x = 0.\) We then see \[ \ba \ln(1 + 0) &= C + 0 - \frac{0^2}{2} + \frac{0^3}{3} - \frac{0^4}{4} + \cdots \nl \implies C &= \ln 1 = 0 \pd \ea \] Thus, \(\eqref{eq:ln(1+x)}\) becomes \[\ln(1 + x) = \boxed{\sum_{n = 0}^\infty (-1)^n \frac{x^{n + 1}}{n + 1}}\]

Power Series, Radius of Convergence, and Interval of Convergence A power series is a polynomial with an infinite number of terms—a series of powers. Its general form is \begin{equation*} \sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n = c_0 + c_1 (x - a) + c_2 (x - a)^2 + \cdots \cma \end{equation*} where \(c_n\) is a coefficient in each term and \(x = a\) is the center of the power series. The values of \(x\) for which a power series converges form its interval of convergence. The endpoints of the interval each extend a distance \(R\)—called the radius of convergence—in either direction of the center of the series, \(x = a.\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) converges at both \(x = a - R\) and \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \([a - R, a + R].\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) converges at \(x = a - R\) and diverges at \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \([a - R, a + R).\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) diverges at \(x = a - R\) and converges at \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \((a - R, a + R].\)

- If \(\sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n\) diverges at both \(x = a - R\) and \(x = a + R,\) then the series' interval of convergence is \((a - R, a + R).\)

If \(R = 0,\) then the series only converges at \(x = a;\) if \(R = \infty,\) then the series converges for all \(x \in \RR.\)

Geometric Power Series A convergent infinite geometric series takes the form \[\frac{1}{1 - r} = 1 + r + r^2 + r^3 + \cdots \cmaa \abs{r} \lt 1 \pd\] Reversing the perspective, we define rational functions as geometric series. For \(\abs x \lt 1,\) the geometric power series is \begin{equation} \frac{1}{1 - x} = 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + \cdots = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty x^n \pd \eqlabel{eq:geo-power-series} \end{equation} We derive many useful power series by manipulating this form, such as by replacing \(x\) with another function.

Differentiating and Integrating Power Series Consider the following power series that has a radius of convergence of \(R \col\) \begin{equation*} f(x) = \sum_{n = 0}^\infty c_n (x - a)^n = c_0 + c_1 (x - a) + c_2 (x - a)^2 + \cdots \pd \end{equation*} Differentiating the power series gives \begin{equation} \ba f'(x) &= c_1 + 2c_2(x - a) + 3c_3(x - a)^2 + \cdots \nl &= \sum_{n = 1}^\infty n c_n (x - a)^{n - 1} \cma \ea \eqlabel{eq:power-series-f'} \end{equation} Integrating the power series gives \begin{equation} \ba \int f(x) \di x &= C + c_0(x - a) + c_1 \frac{(x - a)^2}{2} + c_2 \frac{(x - a)^3}{3} + \cdots \nl &= C + \sum_{n = 0}^\infty \frac{c_n (x - a)^{n + 1}}{n + 1} \pd \ea \eqlabel{eq:power-series-int-f} \end{equation} The power series of \(\eqref{eq:power-series-f'}\) and \(\eqref{eq:power-series-int-f}\) each have a radius of convergence of \(R.\) Differentiating or integrating a power series conserves the radius of convergence but not necessarily the interval of convergence. Thus, when we differentiate or integrate a power series, we must check the endpoints of the interval of convergence.