0.8: Trigonometry

Whereas algebra is the study of operations with numbers, trigonometry is the study of triangles. But the ideas in trigonometry extend far beyond relating triangles' sides and angles; they have applications in broadcasting signals, supplying electricity, and swinging objects—and many other periodic phenomena. In this section we perform a rapid review of trigonometry through the following topics:

- Trigonometry in Right Triangles

- Unit Circle

- Graphs of Trigonometric Functions

- Inverse Trigonometric Functions

- Laws of Sine and Cosine

- Trigonometric Identities

Trigonometry in Right Triangles

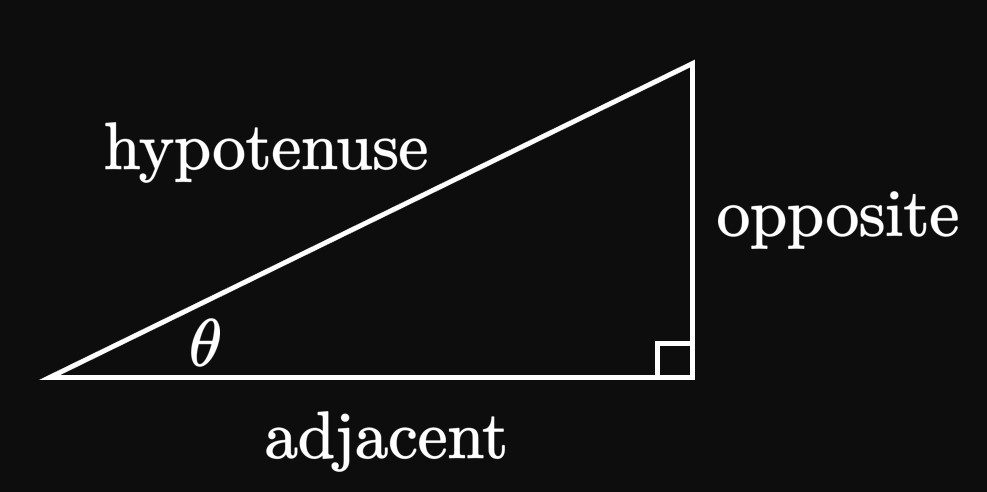

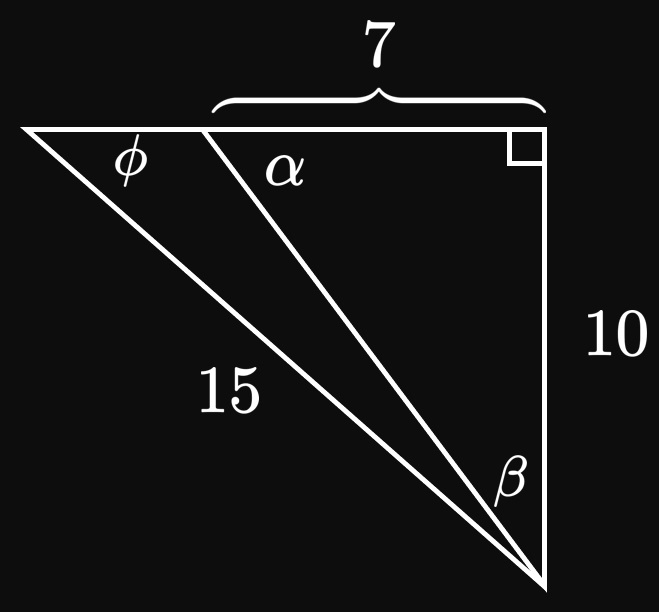

Let's consider a right triangle in which one non-right angle is \(\theta,\)

as in Figure 1.

The leg across from the angle \(\theta\) has a length of \(\text{opposite},\)

just as the leg nearest to the angle has a length of \(\text{adjacent}.\)

Also suppose that the hypotenuse has a length given by \(\text{hypotenuse}.\)

Then the sine of the angle is defined by the ratio

\[\sin \theta = \frac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}} \pd\]

Conversely, the cosine of the angle is given by

\[\cos \theta = \frac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} \pd\]

We also define the tangent of the angle

to be

\[\tan \theta = \frac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} \pd\]

A classic mnemonic for remembering these three trigonometric ratios

is SOH CAH TOA:

By dividing trigonometric ratios, we see \[ \ba \frac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} &= \frac{\dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}}}{\dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}}} \nl \tan \theta &= \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta} \pd \ea \] Through this relationship, \(\tan \theta\) is easily found if \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) are both known.

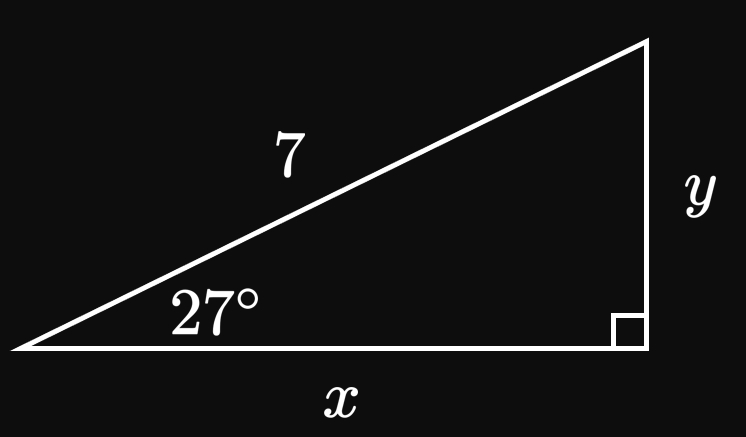

Trigonometric functions can be evaluated using a calculator. Doing so enables us to find the lengths of all the sides of a right triangle if only one side and one non-right angle are known. We can measure an angle either in degrees or in radians; recall that there are \(\pi\) radians in \(180\) degrees.

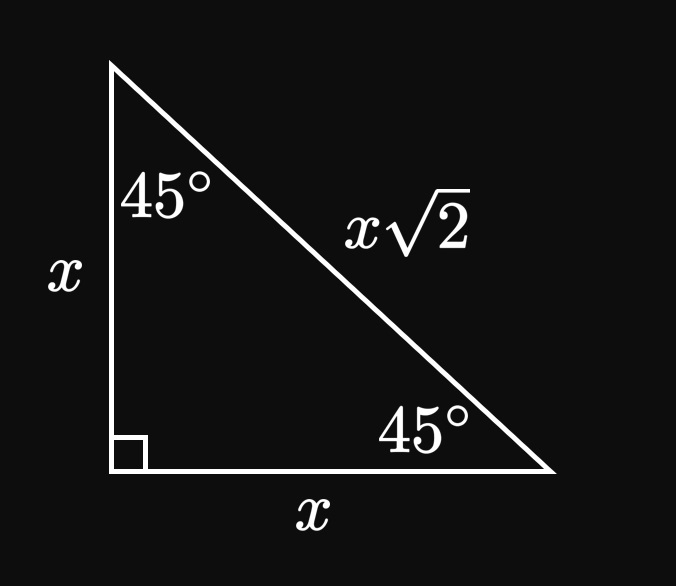

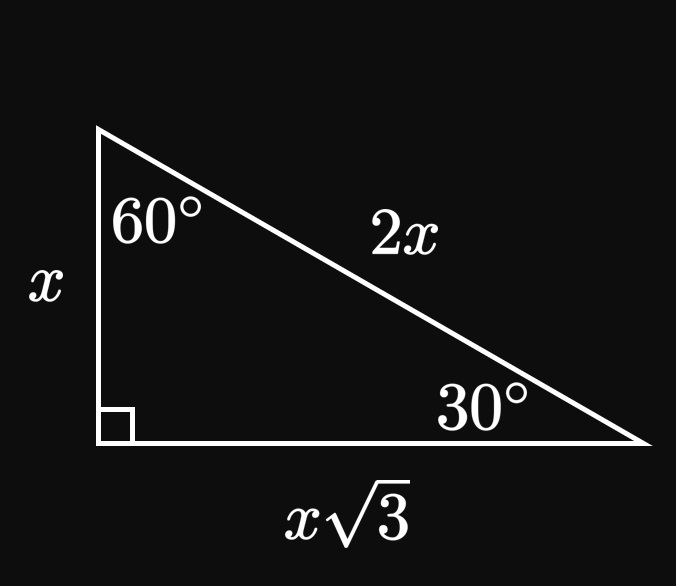

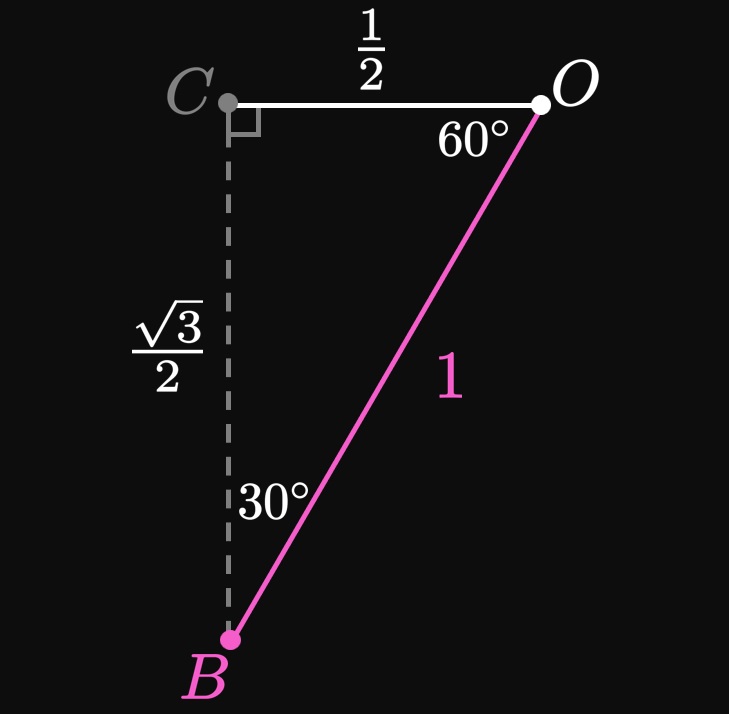

Special Right Triangles While we need a calculator to evaluate most trigonometric expressions, there are a few values of \(\theta\) such that \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) are known exactly. In an isosceles right triangle, both legs have the same length \(x\) and so the angles are \(45 \degree,\) \(90 \degree,\) and \(45 \degree\) (Figure 3A). This special triangle is called the 45–45–90 triangle. Then by the Pythagorean theorem, the hypotenuse's length is \(x \sqrt 2.\) We therefore see \[ \baat{2} \sin 45 \degree &= \frac{x}{x \sqrt 2} &&= \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} &= \frac{\sqrt 2}{2} \cma \nl \cos 45 \degree &= \frac{x}{x \sqrt 2} &&= \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} &= \frac{\sqrt 2}{2} \pd \eaat \] Since \(\tan 45 \degree = (\sin 45 \degree)/(\cos 45 \degree),\) we see \[\tan 45 \degree = \frac{\sqrt 2/2}{\sqrt 2/2} = 1 \pd\] Another special right triangle is formed when the angles are \(60 \degree,\) \(30 \degree,\) and \(90 \degree.\) (It is called the 30–60–90 triangle.) If the leg adjacent to the \(60 \degree\) angle has length \(x,\) then the other leg has length \(x \sqrt 3\) (adjacent to the \(30 \degree\) angle) and the hypotenuse has length \(2x.\) (See Figure 3B.) Then we see \[\sin 60 \degree = \frac{x \sqrt 3}{2x} = \frac{\sqrt 3}{2} \lspace \cos 60 \degree = \frac{x}{2x} = \frac{1}{2} \pd\] We also observe \[ \sin 30 \degree = \cos 60 \degree = \frac{1}{2} \lspace \cos 30 \degree = \sin 60 \degree = \frac{\sqrt 3}{2} \pd \] It then follows that \[\tan 30 \degree = \frac{1/2}{\sqrt 3/2} = \frac{\sqrt 3}{3} \lspace \tan 60 \degree = \frac{\sqrt 3/2}{1/2} = \sqrt 3 \pd\] The following table summarizes these results. Since we use these values often, it is imperative to have them memorized.

| \(\theta\) | \(\sin \theta\) | \(\cos \theta\) | \(\tan \theta\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(30 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{6}\) | \(\ds \frac{1}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{3}\) |

| \(45 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\) | \(1\) |

| \(60 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{3}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{1}{2}\) | \(\ds \sqrt 3\) |

Reciprocal Trigonometric Functions In calculus we often work with complicated combinations of sine and cosine. Hence, it is sometimes convenient to use the three reciprocal functions cosecant \((\csc \theta),\) secant \((\sec \theta),\) and cotangent \((\cot \theta),\) defined as follows: \[\csc \theta = \frac{1}{\sin \theta} \cmaa \sec \theta = \frac{1}{\cos \theta} \cmaa \cot \theta = \frac{1}{\tan \theta} \pd\]

Unit Circle

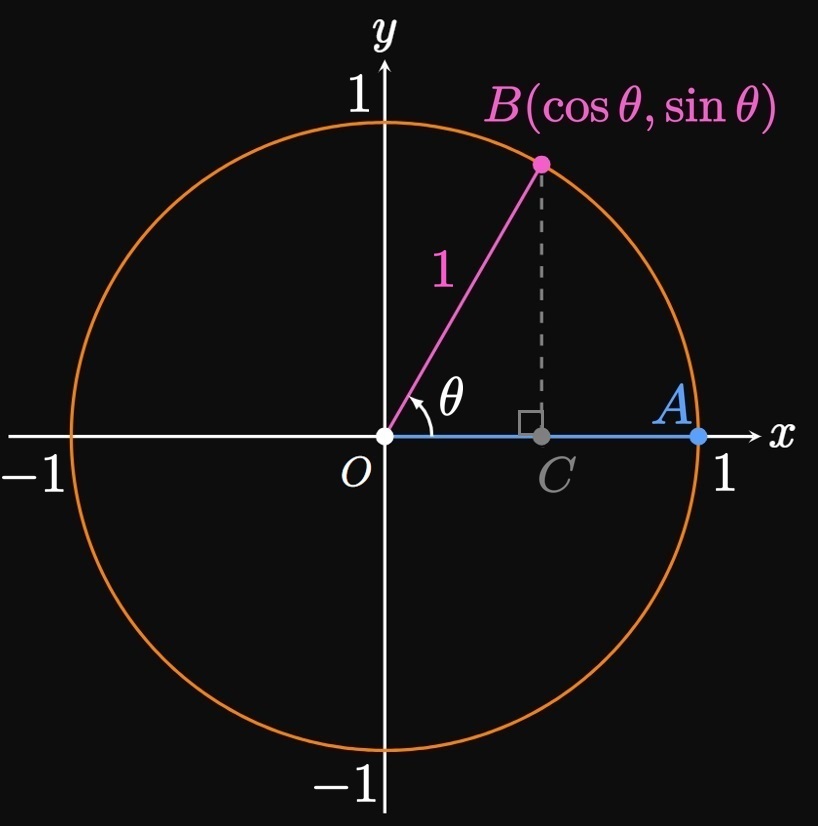

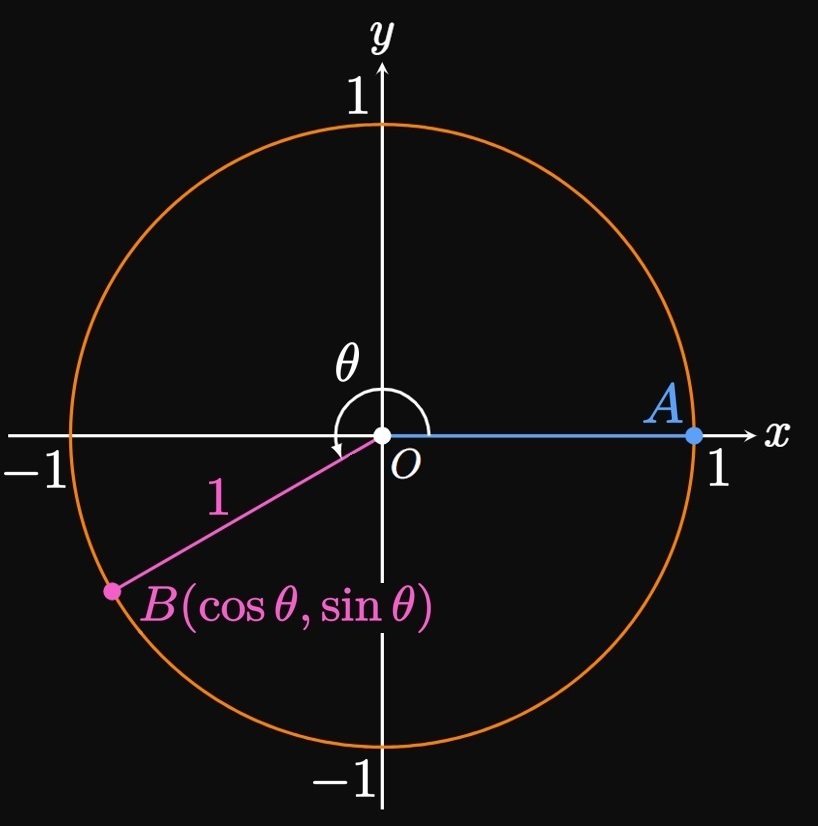

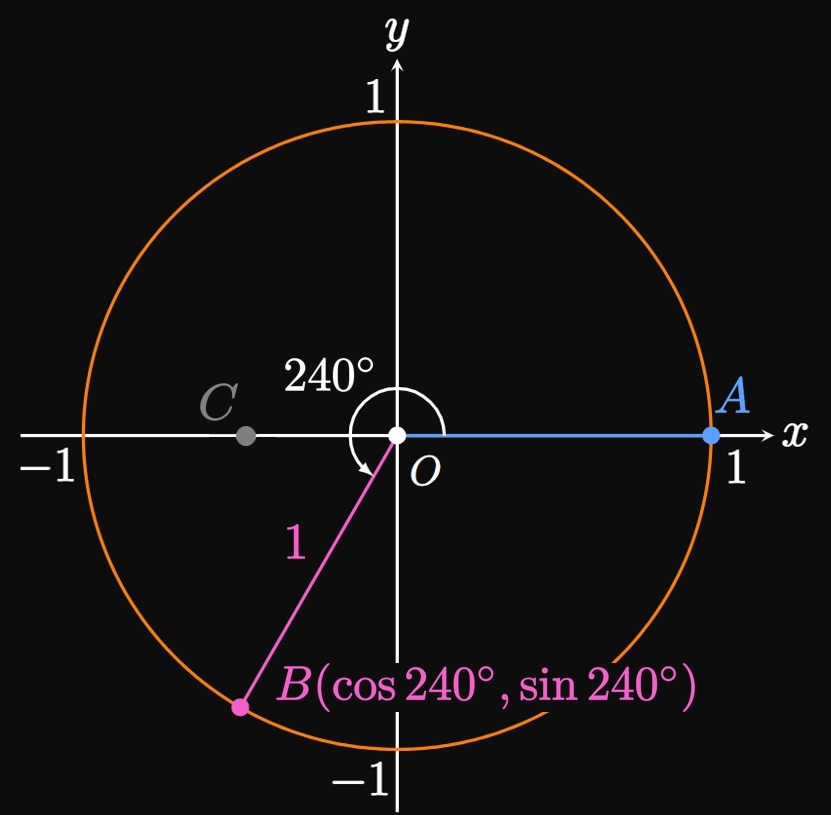

Whereas the right triangle provides simple definitions of the sine, cosine, and tangent functions, the domain of these functions is limited to \(0 \lt \theta \lt 90 \degree.\) (Otherwise, the triangle would be invalid.) But we're interested in extending these functions' domains; many physical phenomena rely on sine and cosine to be defined for all real numbers. We construct a circle of radius \(1\)—called the Unit Circle, since its radius is a single unit—centered at the origin. Let \(\theta\) be the angle subtended between the initial side \(\segment{OA}\) and the terminal side \(\segment{OB}.\) Side \(\segment{OA}\) is static; imagine rotating the side \(\segment{OB}\) counterclockwise about the pivot \(O\) to increase \(\theta.\) We then define \(\cos \theta\) to be the \(x\)-coordinate of point \(B,\) and we define \(\sin \theta\) to be the \(y\)-coordinate of \(B.\) For example, point \(B\) lands on \((0, 1)\) when the terminal side \(\segment{OB}\) is rotated \(90 \degree\) counterclockwise; hence, \(\cos 90 \degree = 0\) and \(\sin 90 \degree = 1.\) If \(\theta\) is in the first quadrant, as shown by Figure 4A, then we see \(\length{BC} = y\) \(= \sin \theta\) and \(\length{OC} = x\) \(= \cos \theta.\) Thus, the Unit Circle definitions of \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) agree with their definitions using right triangles. But using the Unit Circle, we allow \(\theta\) to rotate past \(90 \degree;\) Figure 4B shows an example in which \(\segment{OB}\) is in the third quadrant.

The same procedure in Example 4 enables us to attain exact values of \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) for many choices of \(\theta\) around the Unit Circle. (See Figure 6.) Just as performing algebra requires that you memorize the Multiplication Table, it is equally vital to know these special values on the Unit Circle for trigonometry. It is helpful to memorize the points in the first quadrant and exploit symmetry to attain the sines and cosines in the other three quadrants.

When \(\theta\) is \(360 \degree\) (or \(2 \pi\) radians) on the Unit Circle, \(\segment{OB}\) reaches the same position as \(\segment{OA};\) as we increase \(\theta\) further, \(\segment{OB}\) is again traced out in a counterclockwise path. Thus, \(\segment{OB}\) lands in the same position if it is rotated \(360 \degree\) (or \(2 \pi\) radians) counterclockwise or clockwise. The angles \(\theta\) and \(\theta \pm 2 \pi\) are therefore said to be coterminal; they produce the same position of the terminal side \(\segment{OB}.\) So we also have the same values of sine and cosine—namely, \begin{equation} \sin \theta = \sin (\theta \pm 2 \pi) \lspace \cos \theta = \cos (\theta \pm 2 \pi) \pd \label{eq:sin-cos-2pi} \end{equation} On the other hand, \(\theta\) is decreasing if we rotate \(\segment{OB}\) clockwise. For example, an angle of \(\theta = -30 \degree\) places \(\segment{OB}\) in the fourth quadrant. Then \(\sin(-30 \degree)\) \(= \sin 330 \degree\) \(= -1/2.\) Thus, the Unit Circle enables us to extend the domain of the sine and cosine functions to all real numbers.

Graphs of Trigonometric Functions

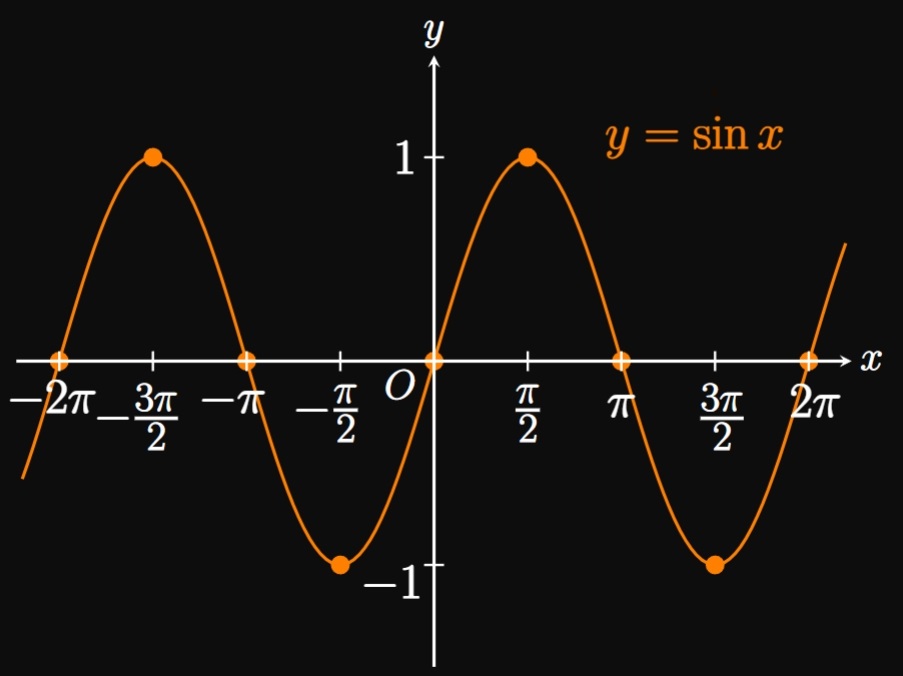

From Figure 6 we can gather values of

\(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) for several choices of \(\theta.\)

By plotting the values of \(\theta\) on the horizontal axis and

the values of \(\sin \theta\) on the vertical axis, we attain the graph of \(y = \sin x\) in

Figure 7A.

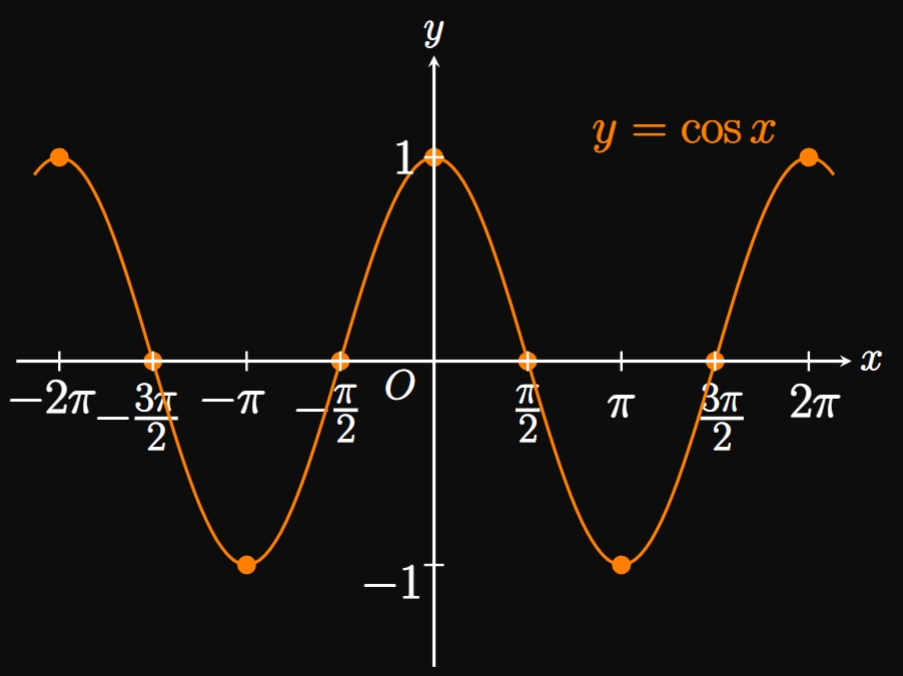

Doing the same procedure for \(\cos \theta\) yields the graph of \(y = \cos x\) in

Figure 7B.

These graphs are called periodic because they contain endless waves,

which repeat after \(2 \pi\) radians, as consistent with \(\eqref{eq:sin-cos-2pi}.\)

(The period,

the time in which a trigonometric function completes one revolution,

is therefore \(2 \pi\) for \(\sin x\) and

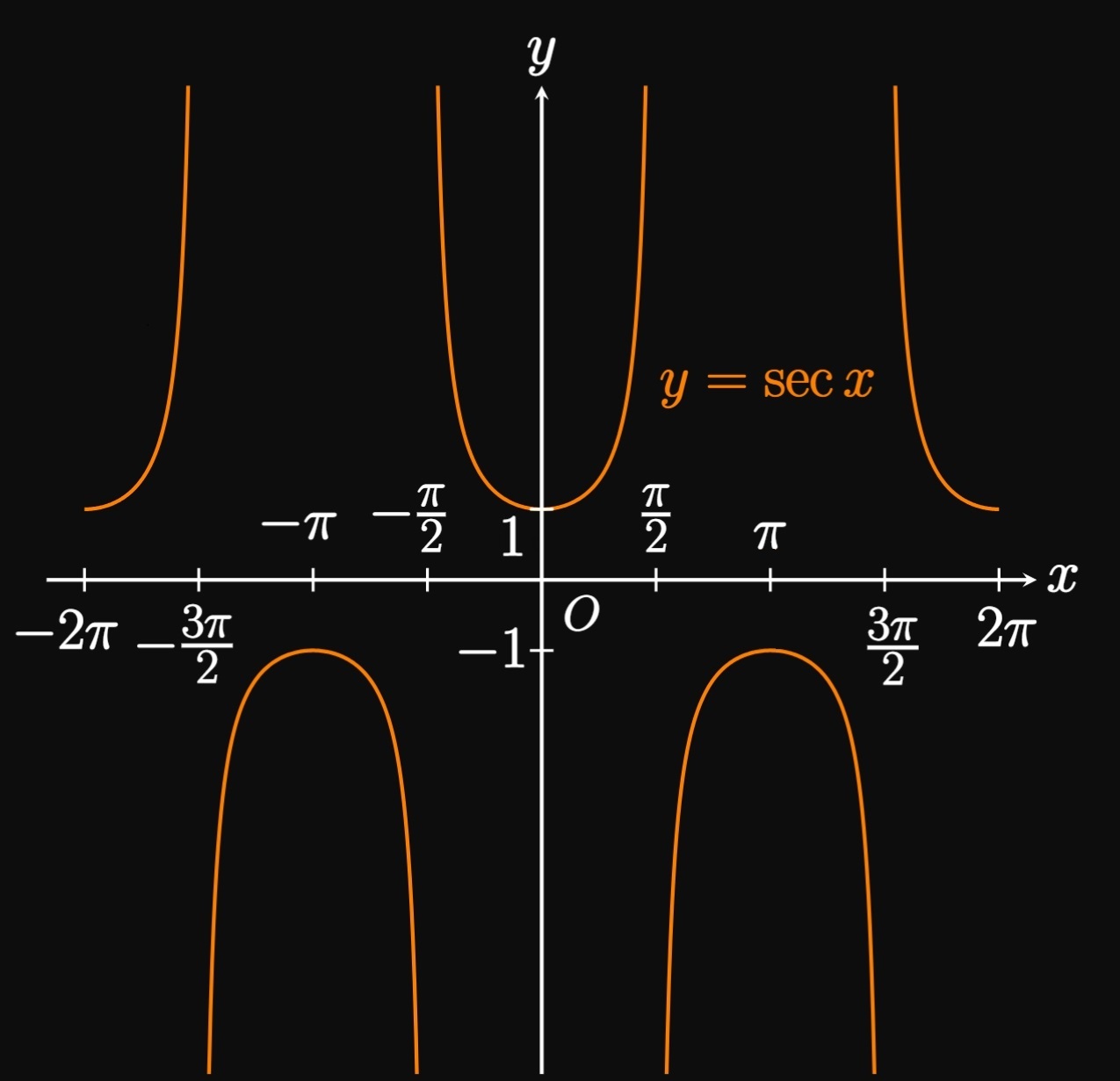

By a similar method, we attain the graphs of \(y = \csc x\) (Figure 8A)

and \(y = \sec x\) (Figure 8B).

Note that \(y = \csc x\) has vertical asymptotes—vertical lines at which the graph

becomes unbounded (approaching \(\infty\) or

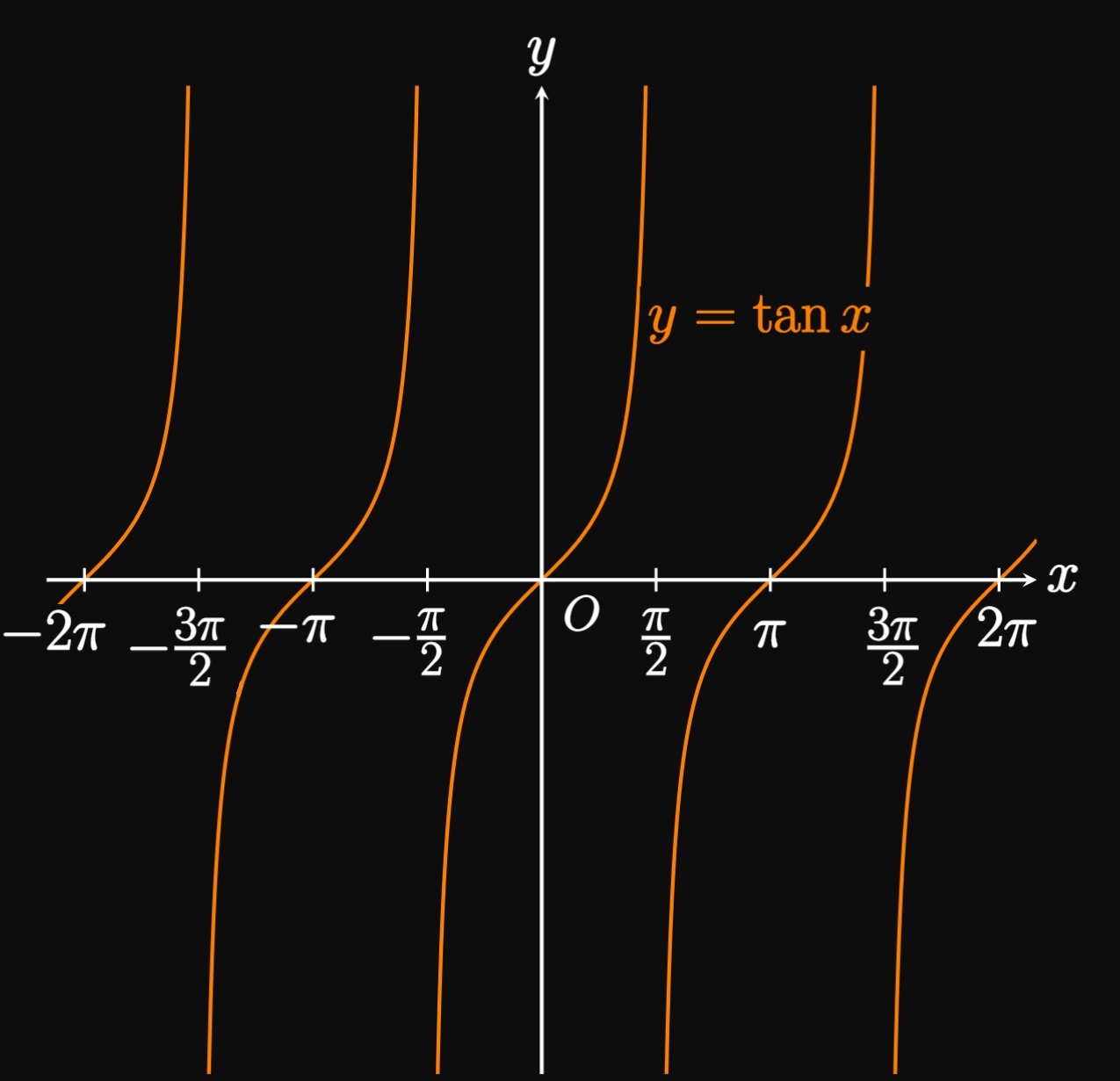

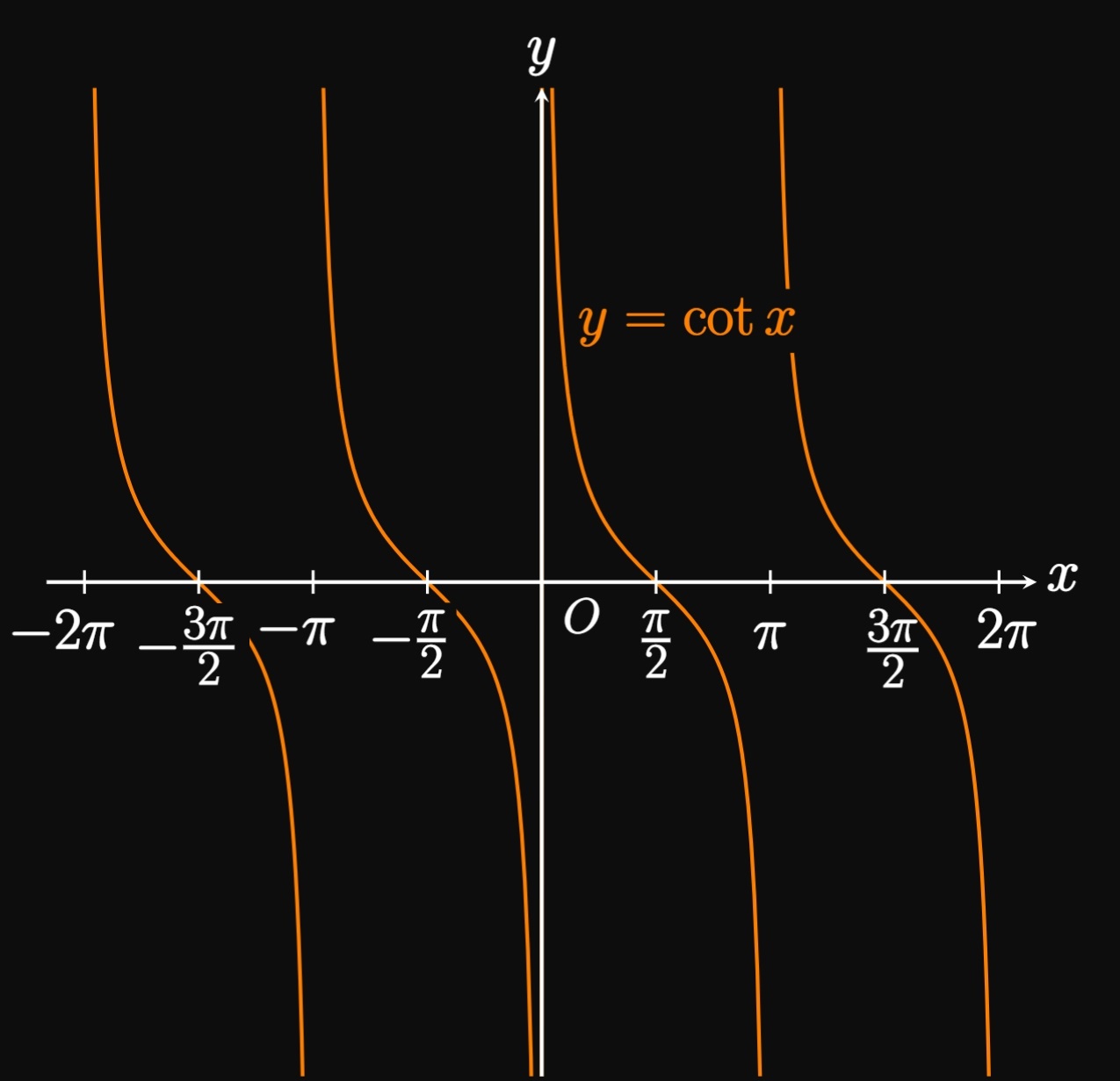

Now we investigate the graphs of tangent and cotangent. The curve \(y = \tan x\) (Figure 9A) has vertical asymptotes at \(x = \pm \pi/2,\) \(x = \pm 3\pi/2,\) \(x = \pm 5 \pi/2, \dots.\) Its domain is therefore \(x \ne \pi/2 \pm n \pi\) for all integers \(n.\) But the curve \(y = \cot x\) (Figure 9B) has vertical asymptotes at \(x = 0,\) \(x = \pm \pi,\) \(x = \pm 2 \pi, \dots.\) So its domain is \(x \ne n \pi\) for all integers \(n.\) Unlike the graphs of the other four trigonometric functions, \(y = \tan x\) and \(y = \cot x\) each have a period of \(\pi\) and a range of all real numbers.

| Graph | Domain | Range | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(y = \sin x\) | all \(x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \cos x\) | all \(x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \csc x\) | \(\ds x \ne n \pi\) | \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \sec x\) | \(\ds x \ne \frac{\pi}{2} \pm n \pi\) | \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \tan x\) | \(\ds x \ne \frac{\pi}{2} \pm n \pi\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \(\pi\) |

| \(y = \cot x\) | \(\ds x \ne n \pi\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \(\pi\) |

Inverse Trigonometric Functions

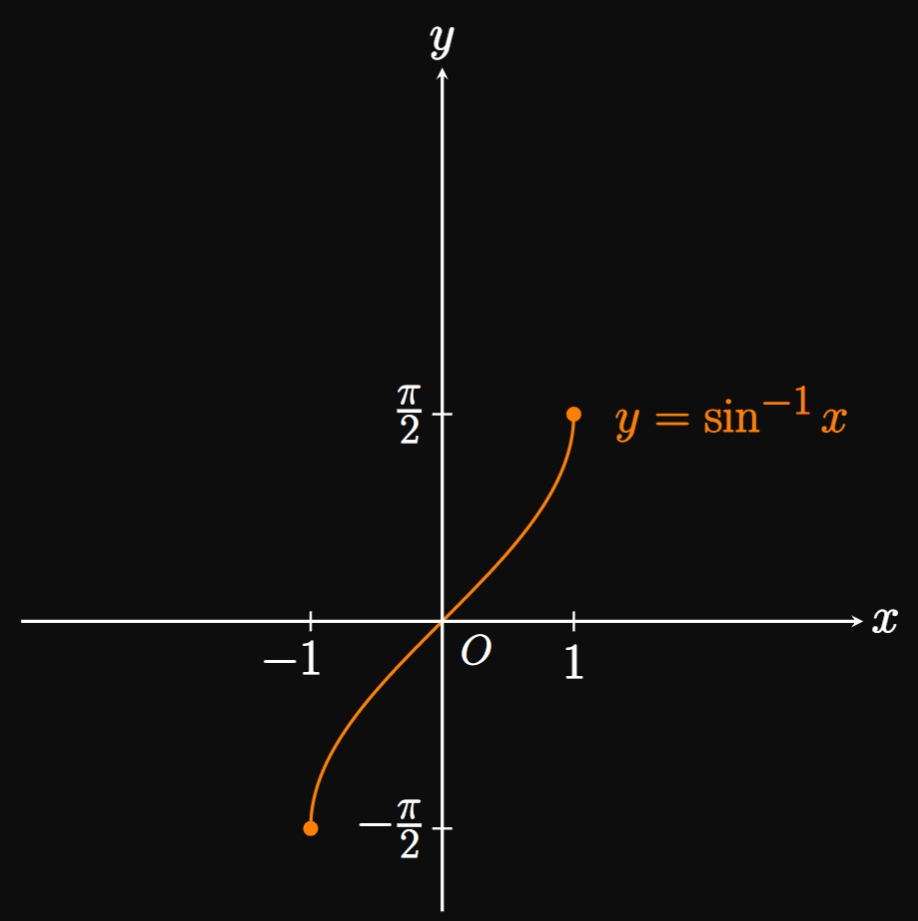

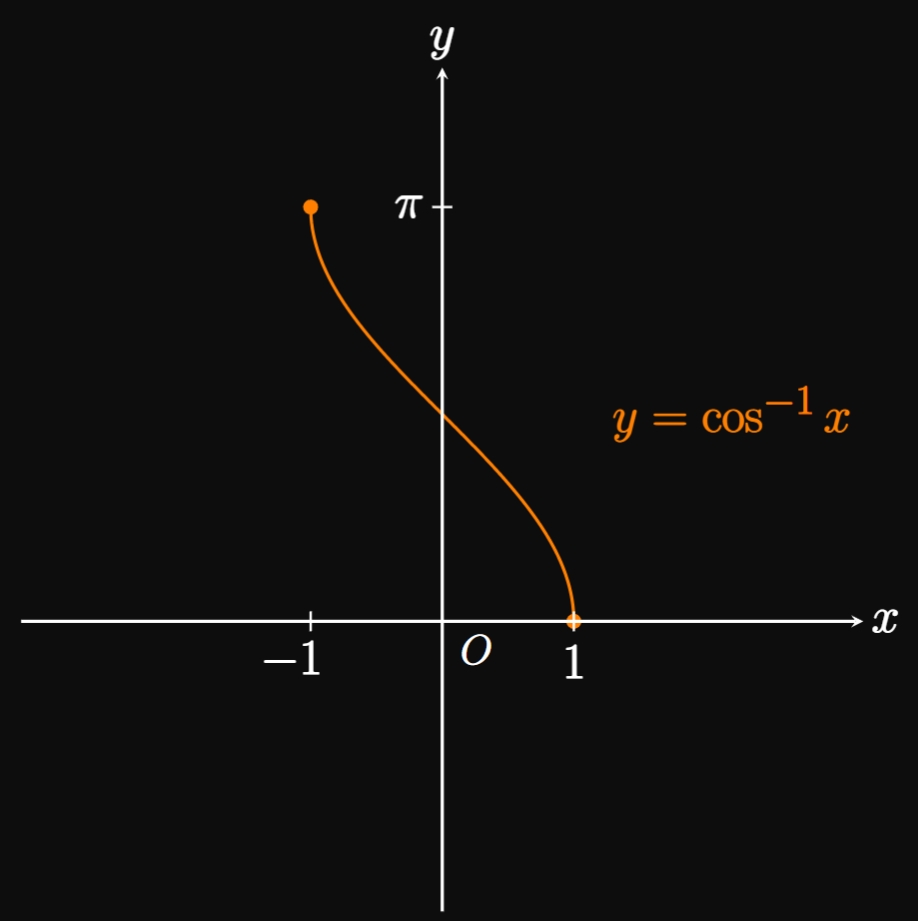

The functions \(y = \sin x\) and \(y = \cos x\) are not inherently invertible. Yet their inverse functions would have great utility, enabling us to find an angle that corresponds to a given trigonometric ratio. Let's define inverse functions of sine and cosine based on half a full wave, which touches both the minimum and maximum values only once. We restrict sine's domain to \([-\pi/2, \pi/2];\) then the graph's range is still \([-1, 1],\) but it passes the Horizontal Line Test. So we define the inverse function of \(f(x) = \sin x\) to be \(\inv f(x) = \asin x,\) whose domain is \([-1, 1]\) and range is \([-\pi/2, \pi/2].\) (See Figure 10A.) Likewise, we restrict the domain of cosine to \([0, \pi];\) doing so yields an invertible portion of \(y = \cos x\) whose range of \([-1, 1]\) is preserved. We therefore define the inverse function of \(f(x) = \cos x\) to be \(\inv f(x) = \acos x,\) whose domain is \([-1, 1]\) and range is \([0, \pi].\) (See Figure 10B.) These definitions enable us to input any trigonometric ratio \(x \in [-1, 1]\) into \(y = \asin x\) and \(y = \acos x;\) these functions then output an angle \(y\) whose sine or cosine is \(x.\)

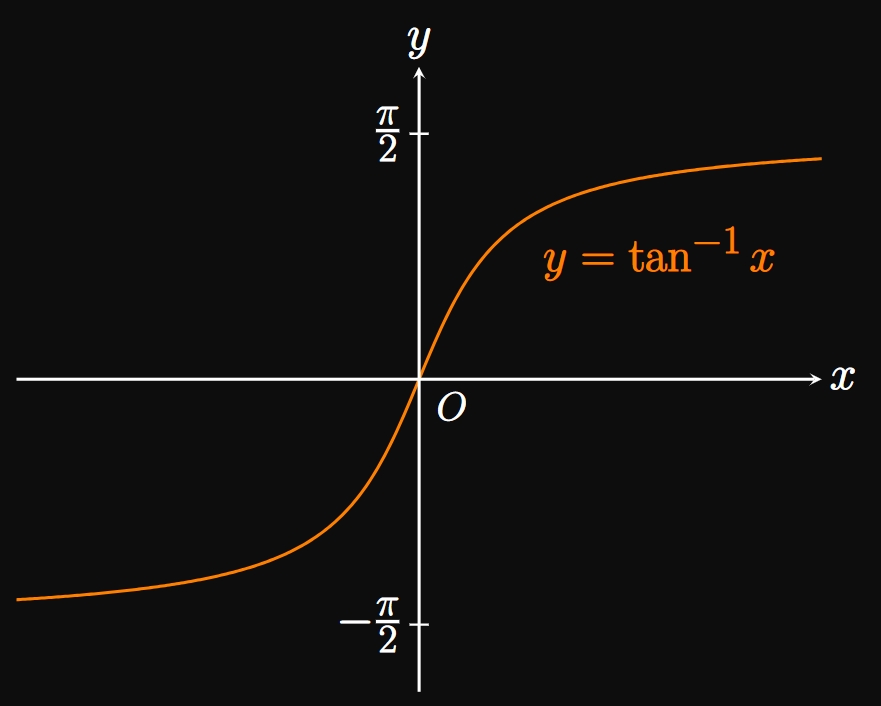

Similarly, the graph of \(y = \tan x\) becomes invertible if we restrict the domain to \((-\pi/2, \pi/2).\)

Since the range of tangent is \((-\infty, \infty),\) the domain of \(y = \atan x\) is \((-\infty, \infty);\)

its range is \((-\pi/2, \pi/2).\)

By making \(x\) larger and larger—that is, by letting \(x\) grow without bound—the graph of \(y = \atan x\) approaches

the value \(\pi/2.\)

Likewise, by letting \(x\) decrease without bound (toward

REMARK By the laws of exponents, \(k^{-1}\) is equivalent to \(1/k\) for any nonzero \(k.\) Yet the inverse prefix on a function does not imply a reciprocal function; thus, \[\asin x \ne \frac{1}{\sin x} = \csc x \pd\] To avoid this confusion, some texts use the arc- prefix to denote an inverse trigonometric function—for example, \[\arcsin x = \asin x \pd\] This notation is chosen since \(\asin x\) \(= \arcsin x\) returns the angle that intercepts the arc on the Unit Circle whose sine is \(x.\) The inverse trigonometric functions \(\acsc x,\) \(\asec x,\) and \(\acot x\) also exist, but we have little use for them in this section. (To find an angle given the side lengths of a right triangle, only inverse sine, inverse cosine, and inverse tangent are necessary.)

| Graph | Domain | Range |

|---|---|---|

| \(y = \asin x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \([-\pi/2, \pi/2]\) |

| \(y = \acos x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \([0, \pi]\) |

| \(y = \atan x\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \((-\pi/2, \pi/2)\) |

CAUTION The inverse trigonometric functions can be misleading. Since the range of \(\asin x\) is \([-\pi/2, \pi/2],\) inverse sine cannot return angles in the second or third quadrants of the Unit Circle. Likewise, the range of \(\acos x\) is \([0, \pi],\) meaning the function cannot output angles in the third or fourth quadrants of the Unit Circle. And because the range of \(\atan x\) is \((-\pi/2, \pi/2),\) inverse tangent only yields angles in the first and fourth quadrants. For example, if you desire the angle \(\theta\) in the third quadrant for which \(\sin \theta = -\sqrt 3/2,\) then you have \(\asin (-\sqrt 3/2)\) \(= -\pi/3,\) an angle in the fourth quadrant—thus misleading you. Instead, consult the Unit Circle in Figure 6 to see \(\theta = 4 \pi/3.\) (We employed this strategy in Example 5 and Example 6.)

RADIAN mode instead of DEGREE mode.)

- \(\asin \par{\sin 60 \degree}\)

- \(\asin \par{\sin 240 \degree}\)

- The value \(60 \degree\) is in the range of inverse sine. So by the definition of inverse functions, we get \[\asin \par{\sin 60 \degree} = \boxed{60 \degree}\]

-

Observe that \(240 \degree\) is not

in the range of inverse sine.

We therefore cannot

cancel out

the sine with the inverse sine. Instead, note that \(\sin 240 \degree = -\sqrt 3/2,\) so \[\asin \par{\sin 240 \degree} = \asin \par{-\frac{\sqrt 3}{2}} = \boxed{-60 \degree}\]

- \(\cos \par{\acos 1}\)

- \(\cos \par{\acos 2}\)

- Because cosine and inverse cosine are inverse functions, and \(1\) is in the range of cosine, we have \[\cos \par{\acos 1} = \boxed 1\]

- It is wrong to write \[\cos \par{\acos 2} = 2\] because cosine's range is \([-1, 1],\) so cosine cannot output the value \(2.\) In fact, the expression \(\acos 2\) is undefined; hence, \(\cos \par{\acos 2}\) is undefined.

Laws of Sine and Cosine

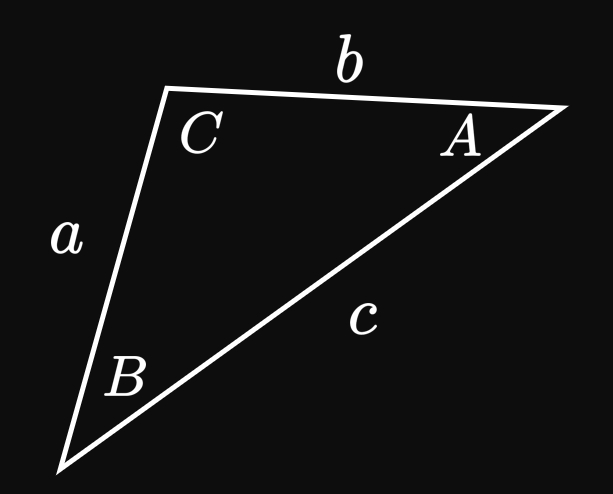

Using the six trigonometric ratios, it is easy to find all the parts of a right triangle. But these ratios cannot be used for non-right triangles, so let's discuss two additional laws that relate the lengths and angles of any triangle. In Figure 13 the non-right triangle's sides have lengths \(a,\) \(b,\) and \(c.\) The angles opposite to these sides are, respectively, \(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C.\) By the Law of Sines, \begin{equation} \frac{\sin A}{a} = \frac{\sin B}{b} = \frac{\sin C}{c} \pd \label{eq:law-sin} \end{equation} In words, for all three angles in a triangle, the ratio of any angle's sine to its opposite side is the same. Conversely, the Law of Cosines gives \begin{equation} c^2 = a^2 + b^2 - 2ab \cos C \pd \label{eq:law-cos} \end{equation}

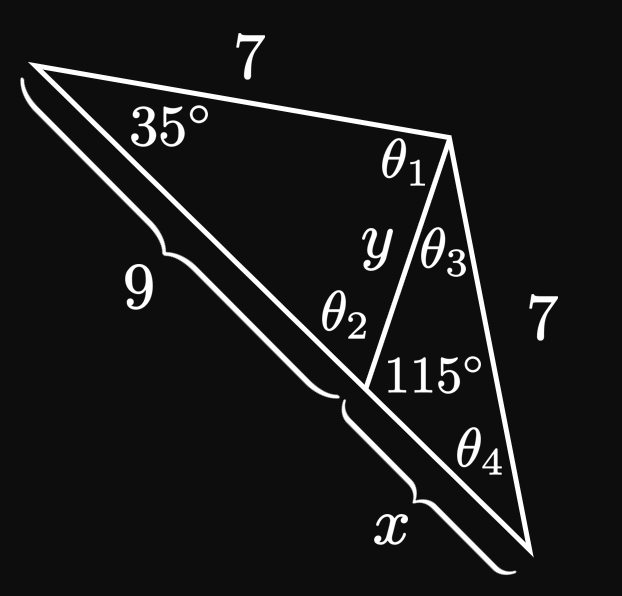

Triangle on the Left Using the Law of Cosines, we have \[ \ba y^2 &= 7^2 + 9^2 - 2(7)(9) \cos 35 \degree \nl y^2 &= 26.787 \nl \implies y &\approx 5.176 \pd \ea \] Then by the Law of Sines, \[\frac{\sin \theta_1}{9} = \frac{\sin \theta_2}{7} = \frac{\sin 35 \degree}{5.176} \pd\] We therefore attain \[ \ba \frac{\sin \theta_2}{7} &= \frac{\sin 35 \degree}{5.176} \nl \theta_2 &= \asin \par{\frac{7 \sin 35 \degree}{5.176}} \nl \implies \theta_2 &\approx 50.869 \degree \pd \ea \] The angles \(\theta_1,\) \(\theta_2 \approx 50.869 \degree,\) and \(35 \degree\) must add to \(180 \degree,\) so \[\theta_1 = 180 \degree - 35 \degree - 50.869 = 94.187 \degree \pd\] (Since \(\theta_1\) is opposite the longest side, it must be obtuse.)

Triangle on the Right The Law of Sines gives \[\frac{\sin 115 \degree}{7} = \frac{\sin \theta_3}{x} = \frac{\sin \theta_4}{5.176} \pd\] Then \[\theta_4 = \asin \par{\frac{5.176 \sin 115 \degree}{7}} \approx 42.079 \degree \pd\] Since the angles \(\theta_3,\) \(\theta_4 \approx 42.079 \degree,\) and \(115 \degree\) must sum to \(180 \degree,\) we find \[\theta_3 \approx 180 \degree - 115 \degree - 42.079 \degree = 22.921 \degree \pd\] Thus, we see \[ \ba \frac{\sin 115 \degree}{7} &= \frac{\sin 22.921 \degree}{x} \nl \implies x &= \frac{7 \sin 22.921 \degree}{\sin 115 \degree} \approx 3.008 \pd \ea \] Hence, the side lengths are \[ \boxed{\ba x &\approx 3.008\nl y &\approx 5.176\ea} \] The angles are \[ \boxed{ \baat{2} \theta_1 &\approx 94.187 \degree \qquad \theta_2 &&\approx 50.869 \degree \nl \theta_3 &\approx 22.921 \degree \qquad \theta_4 &&\approx 42.079 \degree \eaat} \]

Trigonometric Identities

A trigonometric identity is a relationship between trigonometric functions. The most fundamental property is the Pythagorean identity: \begin{equation} \sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta = 1 \pd \label{eq:pythag-identity} \end{equation} We can derive two other useful variants by performing some division: Dividing both sides of \(\eqref{eq:pythag-identity}\) by \(\cos^2 \theta,\) we get \begin{equation} \tan^2 \theta + 1 = \sec^2 \theta \pd \label{eq:pythag-tan-sec} \end{equation} Likewise, dividing both sides of \(\eqref{eq:pythag-identity}\) by \(\sin^2 \theta\) produces \begin{equation} \cot^2 \theta + 1 = \csc^2 \theta \pd \label{eq:pythag-cot-csc} \end{equation}

PROOF OF \(\eqref{eq:pythag-identity}\) On the Unit Circle (Figure 4A), we have \(x = \cos \theta\) and \(y = \sin \theta.\) The lengths \(\abs x\) \(= \abs{\cos \theta}\) and \(\abs y\) \(= \abs{\sin \theta}\) form a right triangle whose hypotenuse has length \(1.\) So by the Pythagorean Theorem, we have \[ \ba \abs{x}^2 + \abs{y}^2 &= 1^2 \nl \abs{\cos \theta}^2 + \abs{\sin \theta}^2 &= 1 \pd \ea \] Squaring a real number can never produce a negative number, so \(\abs{\cos \theta}^2 = \cos^2 \theta\) and \(\abs{\sin \theta}^2 = \sin^2 \theta.\) Thus, we have derived \(\eqref{eq:pythag-identity}.\) \[\qedproof\]

Addition and Subtraction Identities Using geometry, it can be shown that, for two angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta,\) \begin{align} \sin(\alpha + \beta) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta \cma \label{eq:sin-addition} \nl \cos(\alpha + \beta) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta \pd \label{eq:cos-addition} \end{align} These formulas are called the addition identity for sine and addition identity for cosine, respectively. Since \(\sin(-x) = -\sin x\) and \(\cos(-x) = \cos x,\) replacing \(\beta\) with \(-\beta\) in \(\eqref{eq:sin-addition}\) and \(\eqref{eq:cos-addition}\) gives \begin{align} \sin(\alpha - \beta) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta \cma \label{eq:sin-subtraction} \nl \cos(\alpha - \beta) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta + \sin \alpha \sin \beta \pd \label{eq:cos-subtraction} \end{align} Likewise, these respective equations are called the subtraction identity for sine and subtraction identity for cosine. Dividing \(\eqref{eq:sin-addition}\) by \(\eqref{eq:cos-addition}\) and dividing \(\eqref{eq:sin-subtraction}\) by \(\eqref{eq:cos-subtraction},\) we get \begin{align} \tan(\alpha + \beta) &= \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan \beta}{1 - \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \cma \label{eq:tan-addition} \nl \tan(\alpha - \beta) &= \frac{\tan \alpha - \tan \beta}{1 + \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \cma \label{eq:tan-subtraction} \end{align} assuming that no division by zero occurs. Of course, these equations are called the addition identity for tangent and subtraction identity for tangent, respectively.

Sine and Cosine

Note that \(15 \degree = 45 \degree - 30 \degree.\)

By the subtraction identity for sine, as in \(\eqref{eq:sin-subtraction},\) we get

\[

\ba

\sin 15 \degree &= \sin(45 \degree - 30 \degree) \nl

&= \sin 45 \degree \cos 30 \degree - \cos 45 \degree \sin 30 \degree \nl

&= \par{\frac{\sqrt 2}{2}} \par{\frac{\sqrt 3}{2}} - \par{\frac{\sqrt 2}{2}} \par{\frac{1}{2}} \nl

&= \boxed{\frac{\sqrt 6 - \sqrt 2}{4}}

\ea

\]

Likewise, the subtraction identity for cosine

Tangent We could use the subtraction identity for tangent, but it is far easier to deduce \[ \ba \tan 15 \degree &= \frac{\sin 15 \degree}{\cos 15 \degree} \nl &= \frac{\dfrac{\sqrt 6 - \sqrt 2}{4}}{\dfrac{\sqrt 6 + \sqrt 2}{4}} = \boxed{\frac{\sqrt 6 - \sqrt 2}{\sqrt 6 + \sqrt 2}} \ea \]

More Identities By replacing \(\beta\) with \(\alpha\) in the addition identities, we obtain the following three double-angle identities: \begin{align} \sin 2 \alpha &= 2 \sin \alpha \cos \alpha \cma \label{eq:sin-double-angle} \nl \cos 2 \alpha &= \cos^2 \alpha - \sin^2 \alpha \cma \label{eq:cos-double-angle} \nl \tan 2 \alpha &= \frac{2 \tan \alpha}{1 - \tan^2 \alpha} \pd \label{eq:tan-double-angle} \end{align} Using the Pythagorean identity in conjunction with \(\eqref{eq:cos-double-angle},\) we get \begin{equation} \ba \cos 2 \alpha &= 2 \cos^2 \alpha - 1 \nl &= 1 - 2 \sin^2 \alpha \pd \ea \label{eq:cos-2-square} \end{equation} Of course, many other trigonometric identities exist, but the ones in this section are used frequently in calculus.

Trigonometry in Right Triangles

Trigonometry is the study of triangles,

specifically the relationship between their side lengths and angles.

In a right triangle, let \(\theta\) be any of the two non-right angles.

If \(\text{opposite}\) is the length of the leg across from \(\theta\)

and \(\text{adjacent}\) is the length of the leg beside \(\theta,\) then

\[

\ba

\sin \theta &= \frac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}} \cma \nl

\cos \theta &= \frac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} \cma \nl

\tan \theta &= \frac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} \pd \nl

\ea

\]

By dividing ratios, we prove \(\tan \theta\) \(= (\sin \theta)/(\cos \theta).\)

These trigonometric ratios enable us to find all the parts of a right triangle

if only one non-right angle and one side length are known.

Trigonometric functions can take an argument in either degrees or radians;

there are \(\pi\) radians in \(180\) degrees.

When using a calculator to evaluate a trigonometric expression,

double-check whether the calculator is set to RADIAN mode or DEGREE mode.

The reciprocal trigonometric functions are

\[\csc \theta = \frac{1}{\sin \theta} \cmaa \sec \theta = \frac{1}{\cos \theta} \cmaa \cot \theta = \frac{1}{\tan \theta} \pd\]

Whereas a calculator is needed to calculate most trigonometric expressions,

there are a few trigonometric expressions whose values are known exactly.

In a 45–45–90 triangle the

two legs each have the same length \(x,\) and the hypotenuse has a length of \(x \sqrt 2.\)

In a 30–60–90 triangle

the side adjacent to the \(60 \degree\) angle has length \(x,\)

the side adjacent to the \(30 \degree\) angle has length \(x \sqrt 3,\)

and the hypotenuse's length is \(2x.\)

Accordingly, the following table displays the exact trigonometric ratios for

the angles \(30 \degree,\) \(45 \degree,\) and \(60 \degree.\)

It is crucial that you have these values memorized.

| \(\theta\) | \(\sin \theta\) | \(\cos \theta\) | \(\tan \theta\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(30 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{6}\) | \(\ds \frac{1}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{3}\) |

| \(45 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\) | \(1\) |

| \(60 \degree \;\) or \(\; \ds \frac{\pi}{3}\) | \(\ds \frac{\sqrt 3}{2}\) | \(\ds \frac{1}{2}\) | \(\ds \sqrt 3\) |

Unit Circle

The Unit Circle is a circle of unit \(1\) centered at the origin \(O;\)

it enables us to extend the domain of

sine and cosine functions to all real numbers.

Instead of defining these two functions using right triangles,

we construct two line segments—\(\segment{OA},\) the initial side,

and \(\segment{OB},\) the terminal side.

The angle \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\segment{OA}\) and \(\segment{OB};\)

it increases as \(\segment{OB}\) is rotated counterclockwise about the origin

but decreases as \(\segment{OB}\) is rotated clockwise about the origin.

We define \(\cos \theta\) as the

Graphs of Trigonometric Functions The graphs of all six trigonometric functions are periodic. The following table shows their key properties. Let \(n\) be any integer.

| Graph | Domain | Range | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(y = \sin x\) | all \(x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \cos x\) | all \(x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \csc x\) | \(\ds x \ne n \pi\) | \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \sec x\) | \(\ds x \ne \frac{\pi}{2} \pm n \pi\) | \((-\infty, -1] \cup [1, \infty)\) | \(2 \pi\) |

| \(y = \tan x\) | \(\ds x \ne \frac{\pi}{2} \pm n \pi\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \(\pi\) |

| \(y = \cot x\) | \(\ds x \ne n \pi\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \(\pi\) |

Inverse Trigonometric Functions By restricting the domains of sine, cosine, and tangent, we define the inverse trigonometric functions \(\asin x,\) \(\acos x,\) and \(\atan x\) using the following table. (But using an inverse trigonometric function can be misleading; double-check its range to verify that you will attain the desired angle.)

| Graph | Domain | Range |

|---|---|---|

| \(y = \asin x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \([-\pi/2, \pi/2]\) |

| \(y = \acos x\) | \([-1, 1]\) | \([0, \pi]\) |

| \(y = \atan x\) | \((-\infty, \infty)\) | \((-\pi/2, \pi/2)\) |

Laws of Sine and Cosine The six trigonometric ratios apply only to right triangles; they are useless for non-right triangles. But to relate the side lengths and angles of any triangle, we use the two following laws: Suppose that any triangle has side lengths \(a,\) \(b,\) and \(c,\) which are opposite to the angles \(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C,\) respectively. The Law of Sines gives \begin{equation} \frac{\sin A}{a} = \frac{\sin B}{b} = \frac{\sin C}{c} \pd \eqlabel{eq:law-sin} \end{equation} The Law of Cosines gives \begin{equation} c^2 = a^2 + b^2 - 2ab \cos C \pd \eqlabel{eq:law-cos} \end{equation}

Trigonometric Identities Trigonometric identities relate trigonometric functions to each other. Whereas many trigonometric identities exist, we often use the following identities in calculus. The Pythagorean identity and its variants are as follows: \begin{align} \sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta &= 1 \eqlabel{eq:pythag-identity} \cma \nl \tan^2 \theta + 1 &= \sec^2 \theta \eqlabel{eq:pythag-tan-sec} \cma \nl \cot^2 \theta + 1 &= \csc^2 \theta \eqlabel{eq:pythag-cot-csc} \pd \end{align} For two angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta,\) the addition and subtraction identities for sine are, respectively, \begin{align} \sin(\alpha + \beta) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta + \cos \alpha \sin \beta \cma \eqlabel{eq:sin-addition} \nl \sin(\alpha - \beta) &= \sin \alpha \cos \beta - \cos \alpha \sin \beta \pd \eqlabel{eq:sin-subtraction} \end{align} The addition and subtraction identities for cosine are, respectively, \begin{align} \cos(\alpha + \beta) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta - \sin \alpha \sin \beta \cma \eqlabel{eq:cos-addition} \nl \cos(\alpha - \beta) &= \cos \alpha \cos \beta + \sin \alpha \sin \beta \pd \eqlabel{eq:cos-subtraction} \end{align} Finally, the addition and subtraction identities for tangent are, respectively, \begin{align} \tan(\alpha + \beta) &= \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan \beta}{1 - \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \cma \eqlabel{eq:tan-addition} \nl \tan(\alpha - \beta) &= \frac{\tan \alpha - \tan \beta}{1 + \tan \alpha \tan \beta} \pd \eqlabel{eq:tan-subtraction} \end{align} The double-angle identities are \begin{align} \sin 2 \alpha &= 2 \sin \alpha \cos \alpha \cma \eqlabel{eq:sin-double-angle} \nl \cos 2 \alpha &= \cos^2 \alpha - \sin^2 \alpha \cma \eqlabel{eq:cos-double-angle} \nl \tan 2 \alpha &= \frac{2 \tan \alpha}{1 - \tan^2 \alpha} \pd \eqlabel{eq:tan-double-angle} \end{align} The double-angle identity for cosine can be reexpressed as follows: \begin{equation} \ba \cos 2 \alpha &= 2 \cos^2 \alpha - 1 \nl &= 1 - 2 \sin^2 \alpha \pd \ea \eqlabel{eq:cos-2-square} \end{equation}