7.5: Hydrostatics

If you dive deeper into a body of water, then you feel more pressure on your body due to the increased weight of the water above you. Hydrostatics is the study of water's behavior on a stationary, submerged object. It enables us to test whether a submarine will be crushed in the deep water, or whether a shark can survive at a certain depth.

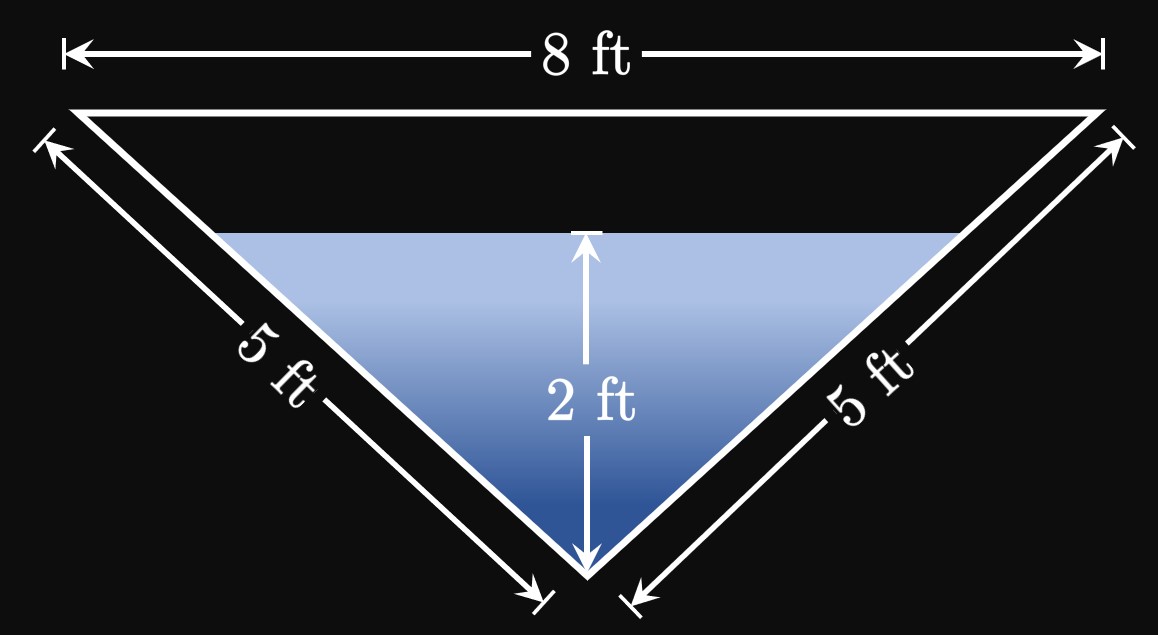

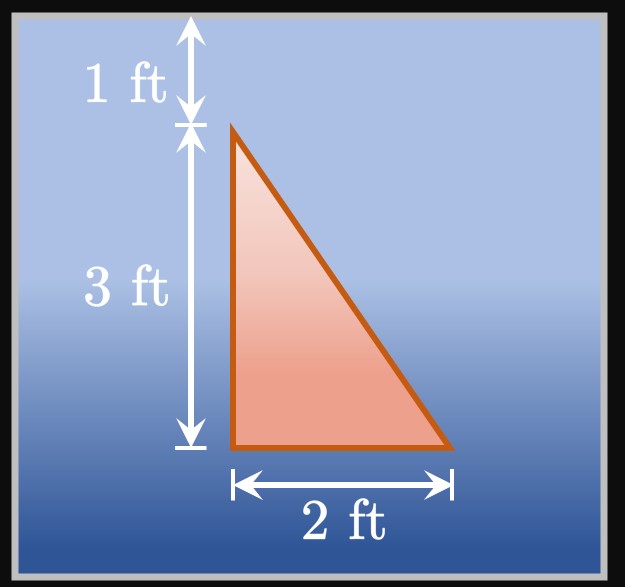

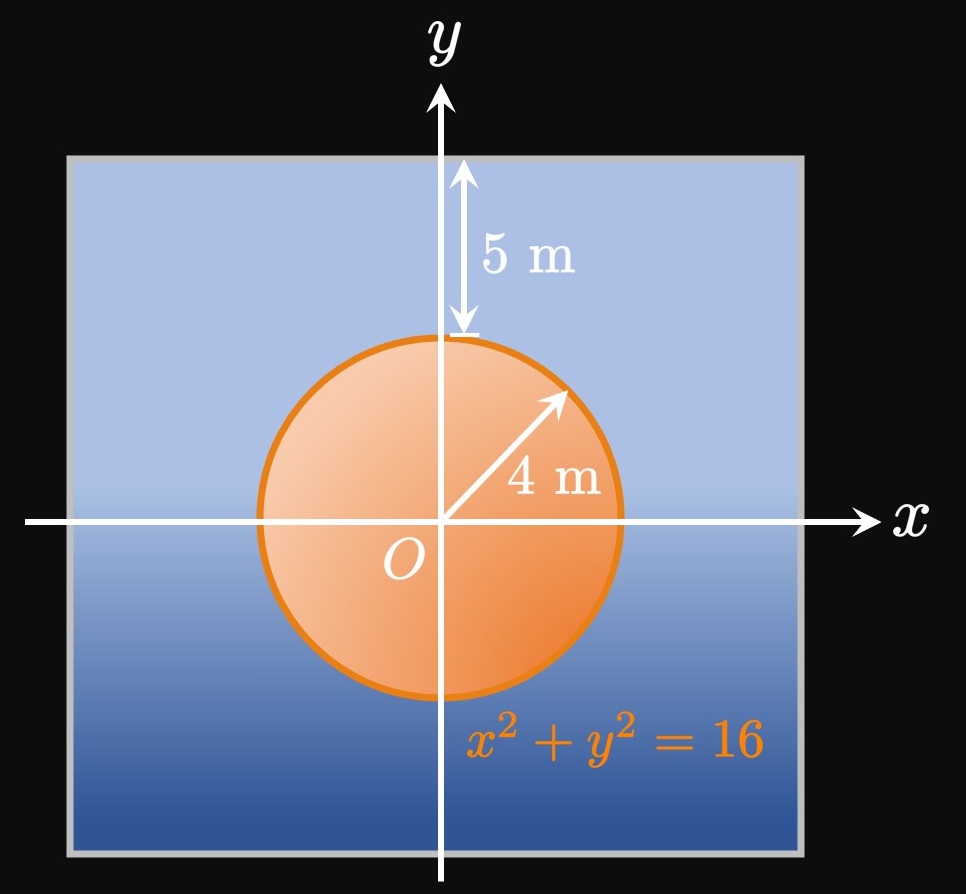

Suppose that a thin, stationary object with area \(A\) is submerged in a body of fluid of density \(\rho\) at a distance of \(h\) below the surface (Figure 1). The hydrostatic force that acts on this body equals the weight of the water above it. The volume of the water above the object is \(Ah,\) and its mass equals its density multiplied by its volume—namely, \(\rho Ah.\) Because weight is the product of mass and the acceleration due to gravity, \(g = 9.8 \undiv{m}{sec}^2\) \(= 32 \undiv{ft}{sec}^2,\) the hydrostatic force acting on the object is \begin{equation} F = \rho A g h \pd \label{eq:h-force} \end{equation} Pressure is defined by the force exerted on an object divided by its area. (A sharp knife exerts high pressure because its edge is so thin.) So the hydrostatic pressure that acts upon the submerged object is \(P = F/A,\) or \begin{equation} P = \rho g h \pd \label{eq:h-pressure} \end{equation} We use \(\eqref{eq:h-force}\) and \(\eqref{eq:h-pressure}\) for a thin object whose depth is uniform. But what if we submerge a bigger body whose depth can't be taken as uniform?

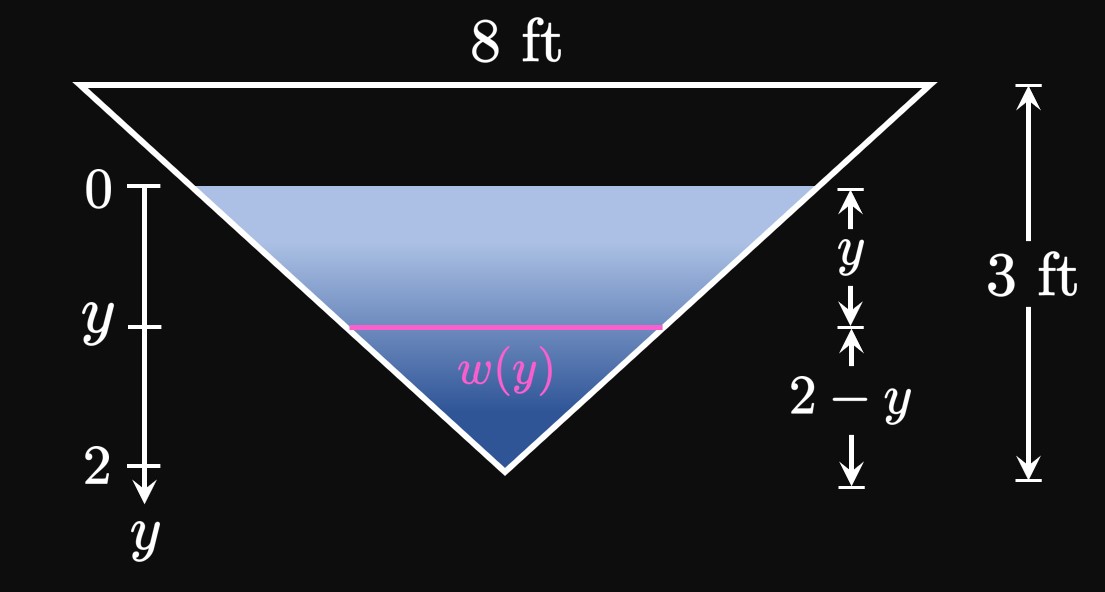

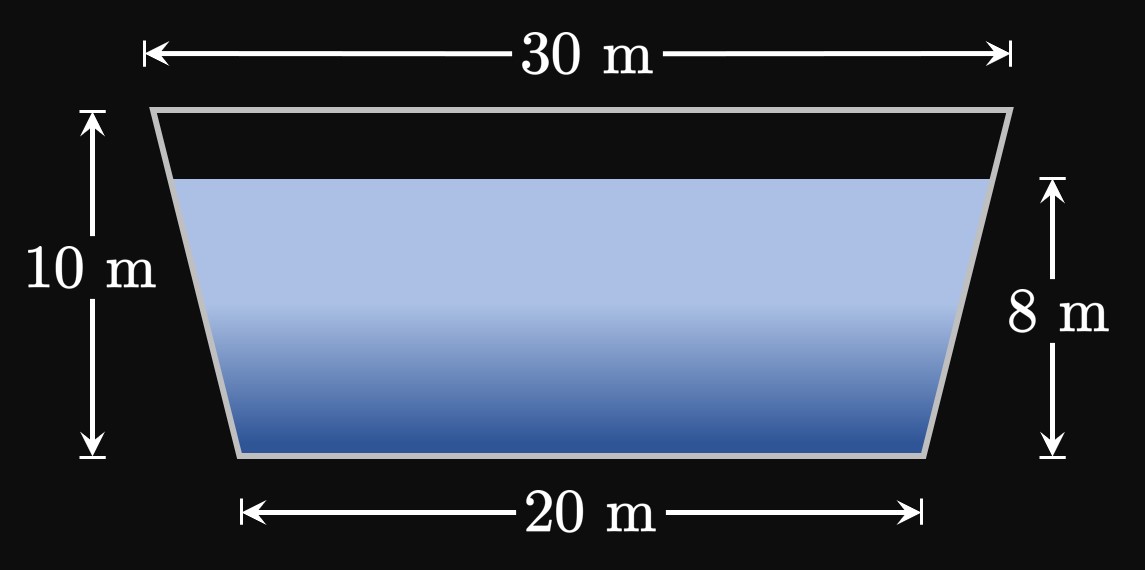

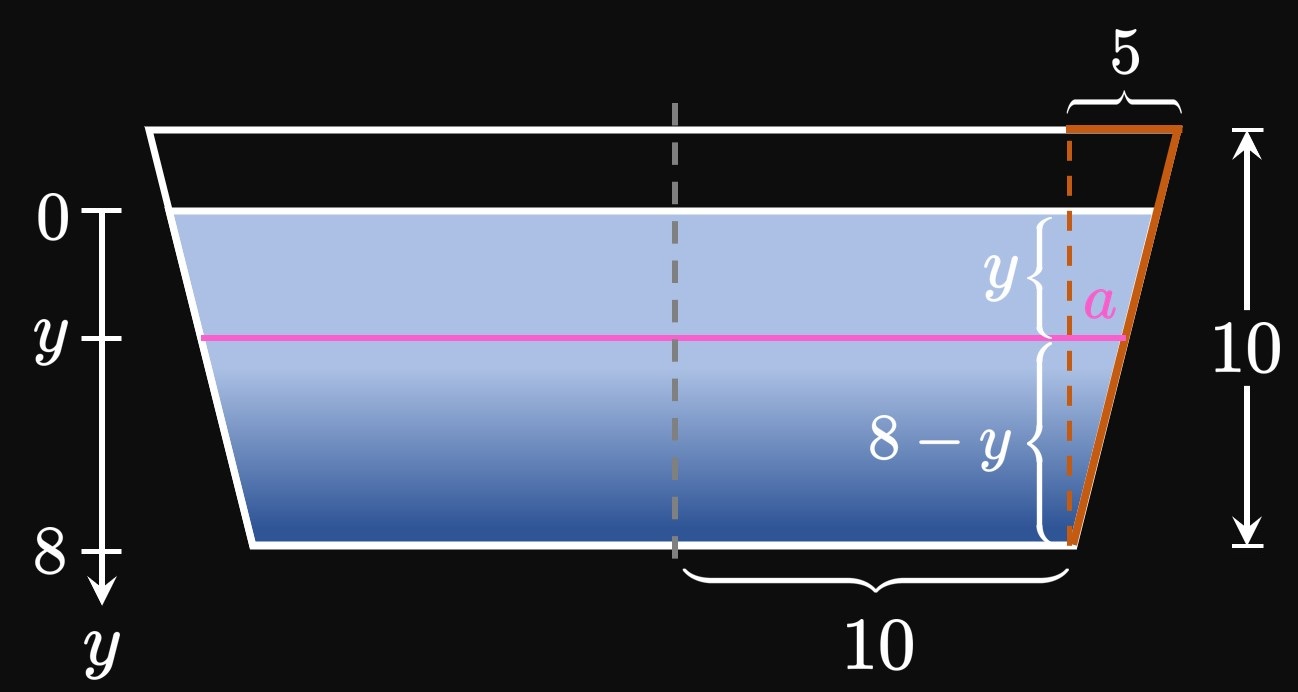

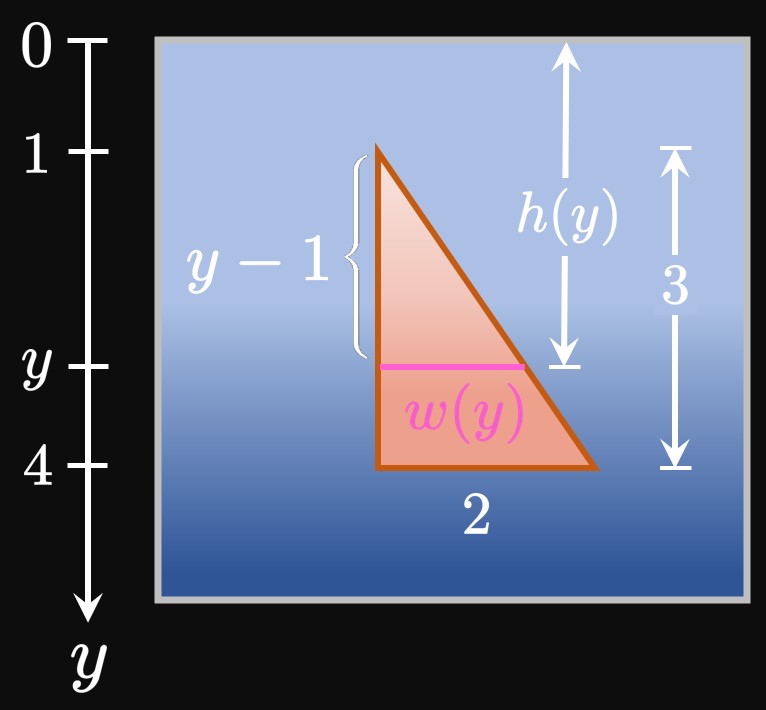

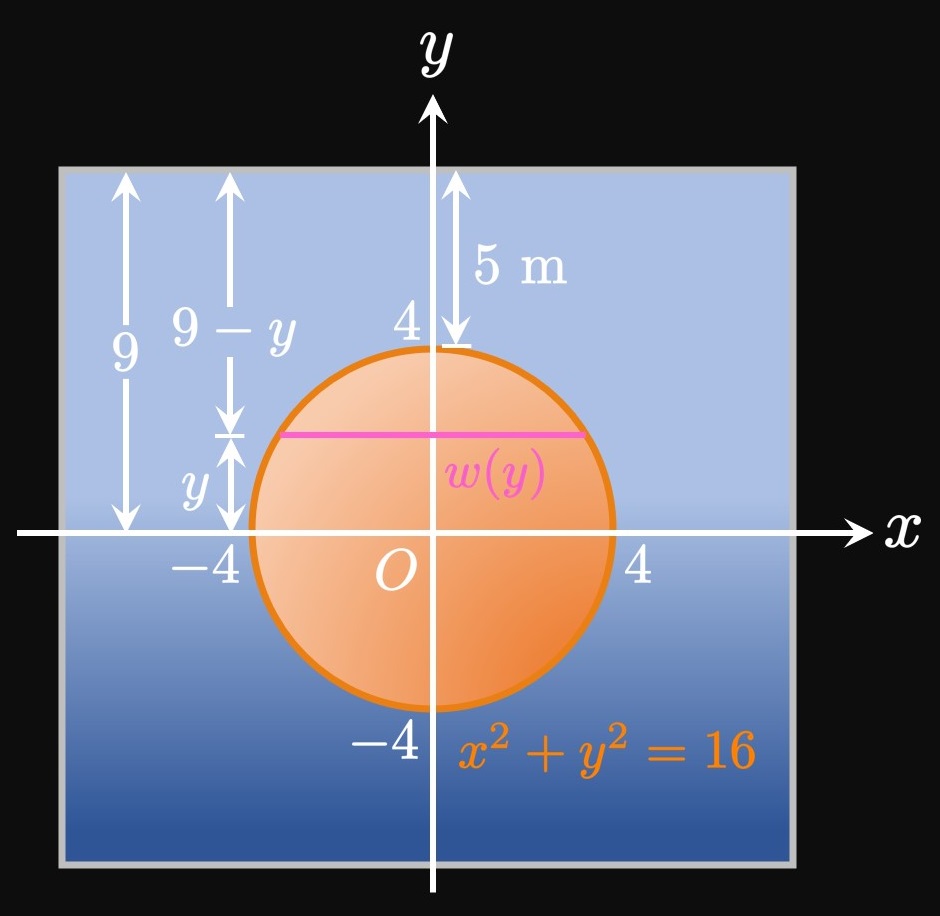

Let's generalize how to calculate the hydrostatic force of a vertical body, as in Figure 2. Suppose that the body is bounded between the lines \(y = a\) and \(y = b.\) We cut the body into \(n\) equal-height horizontal rectangles of endpoints \(a = y_0,\) \(y_1, \dots, y_{n - 1},\) \(y_n = b\) and equal height \(\Delta y.\) In the general subinterval \(\parbr{y_{i - 1}, y_i},\) we pick \(y_i^*\) to be a sample point. If \(w(y)\) is the approximating rectangle's width at \(y,\) then its area is \[A_i = w(y_i^*) \Delta y \pd\] Let \(h(y)\) be the rectangle's depth beneath the water's surface at some \(y.\) If each of the \(n\) rectangles is thin, then the hydrostatic pressure acting on an approximating rectangle is, by \(\eqref{eq:h-pressure},\) roughly \[P_i \approx \rho g h(y_i^*) \pd\] (We assume that each rectangle's depth is uniform.) Then by \(\eqref{eq:h-force},\) the hydrostatic force acting on the rectangle is roughly \[F_i = P_i A_i \approx \rho g h(y_i^*) w(y_i^*) \Delta y \pd\] Summing the hydrostatic forces of all \(n\) rectangles gives a total hydrostatic force of approximately \[F \approx \sum_{i = 1}^n F_i = \sum_{i = 1}^n \rho g h(y_i^*) w(y_i^*) \Delta y \pd\] If we make \(n\) larger, then the rectangles become thinner and so better model the vertical body. Thus, by increasing \(n\) the calculation of the total hydrostatic force increases in accuracy. In other words, \(F\) is the limiting value of the sum as \(n \to \infty \col\) \[F = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i = 1}^n \rho g h(y_i^*) w(y_i^*) \Delta y \pd\] This is a Riemann sum for the function \(\rho g h(y) w(y)\) from \(y = a\) to \(y = b,\) so we attain \begin{equation} F = \rho g \int_a^b h(y) w(y) \di y \pd \label{eq:force-h-body-constants} \end{equation}

Units The International System of Units (SI) is the international standard for measurement. The SI unit for force is the newton, whose symbol is \(\un N.\) One newton is equivalent to a kilogram-meter per second squared; that is, \(1 \un N\) \(= 1 \undiv{kg m}{sec}^2.\) Additionally, water has a density of \(\rho =\) \(1000 \undiv{kg}{m}^3.\) To simplify \(\eqref{eq:force-h-body-constants},\) let's write \(\rho g\) as one number \(\gamma\) (gamma), called the specific weight. In the SI system, \(\gamma = 9.8 \times 1000\) \(= 9800 \undiv{N}{m}^3.\) In the imperial system, \(\gamma = 62.5 \undiv{lb}{ft}^3.\) Hence, we present only a single formula for the hydrostatic force: \begin{equation} F = \gamma \int_a^b h(y) w(y) \di y \pd \label{eq:force-h-body} \end{equation}

For a stationary thin object of area \(A\) that lies a distance \(h\) below the water's surface, the hydrostatic force acting on the object is \begin{equation} F = \rho A g h \cma \eqlabel{eq:h-force} \end{equation} and the hydrostatic pressure is \begin{equation} P = \rho g h \pd \eqlabel{eq:h-pressure} \end{equation} Suppose that a stationary body (whose depth cannot be considered uniform) lies in water between the horizontal lines \(y = a\) and \(y = b.\) At some \(y,\) if \(w(y)\) is the body's width and \(h(y)\) is its depth beneath the surface, then the hydrostatic force acting on the body is \begin{equation} F = \gamma \int_a^b h(y) w(y) \di y \cma \eqlabel{eq:force-h-body} \end{equation} where \(\gamma = 9800\) in SI units and \(\gamma = 62.5\) in imperial units.