7.3: Consumer Surplus and Producer Surplus

In a market, producers and consumers are both driven by benefit. In economics, we need a way to measure how much each party benefits from the sale of an item at some price level. We do so through the following topics:

Consumer Surplus

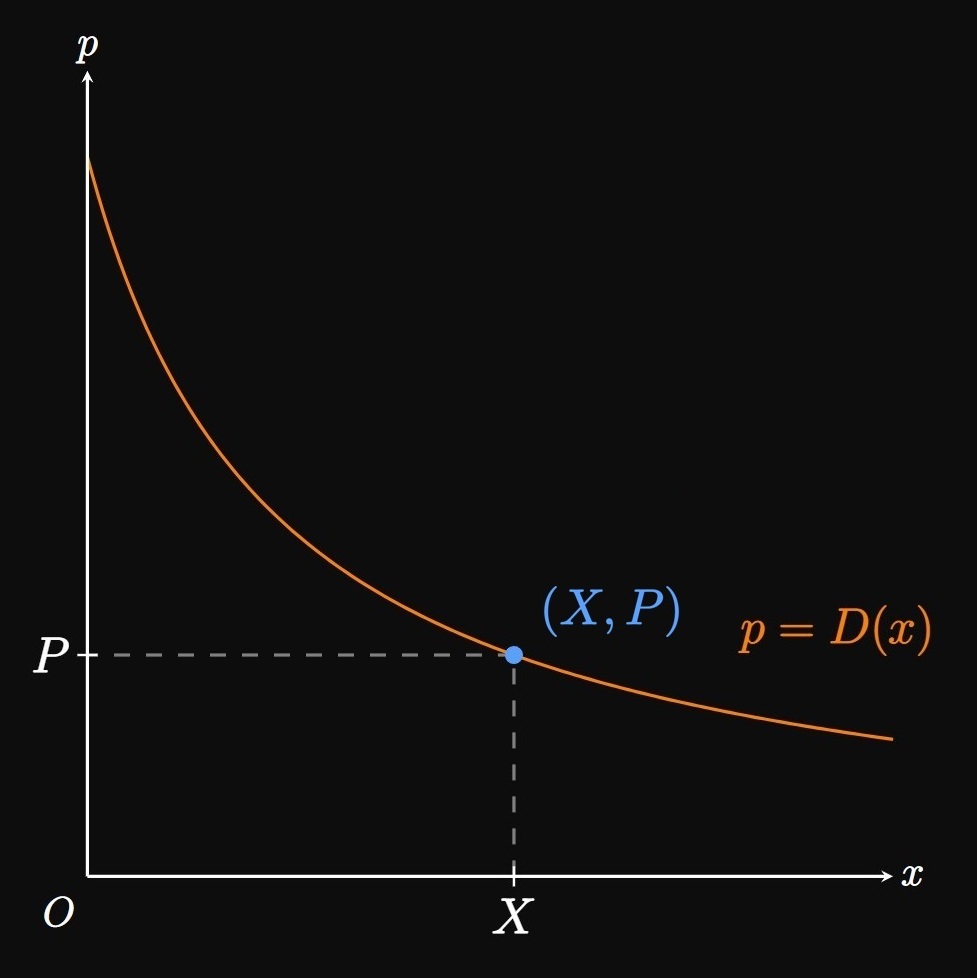

Demand Curves Recall, from Section 3.7, that an inverse relationship exists between price and the number of goods sold (by the Law of Demand). The demand function \(p = D(x)\) models the price per unit that a firm can charge to sell \(x\) units. Figure 1 shows a typical demand curve: We plot \(x\) on the horizontal axis, and we plot the good's price p on the vertical axis. The function \(D(x)\) is the price at which \(x\) units of a commodity are demanded. To sell \(X\) units of a good, a company must sell the product at \(P = D(X)\) dollars.

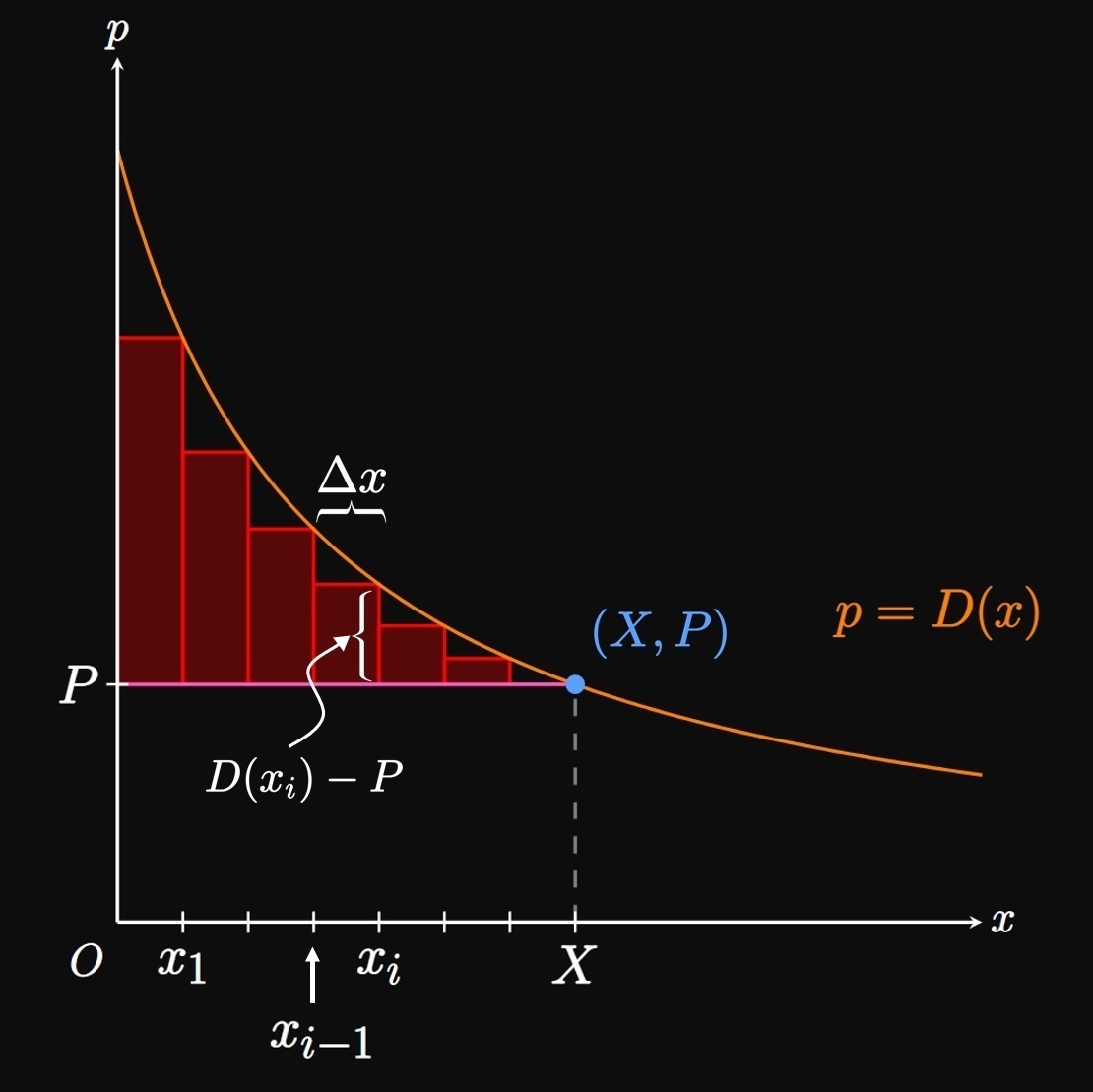

But some consumers are willing to pay more for a product; these shoppers are therefore pleased to pay less. Consumer surplus measures this level of benefit among all customers. To calculate consumer surplus, we divide the interval \([0, X]\) into \(n\) subintervals of endpoints \(0 = x_0,\) \(x_1, \dots,\) \(x_{n - 1}, x_n = X\) and equal width \(\Delta x = X/n.\) Imagine that each subinterval represents a group of \(\Delta x\) items sold. In a general subinterval \([x_{i - 1}, x_i],\) we inscribe a rectangle at the right endpoint \(x_i^* = x_i.\) Observe that \(x_{i - 1}\) units are sold if the price is \(D(x_{i - 1})\) dollars. Yet to increase sales to \(x_i\) units, the price must be lowered to \(D(x_i)\) dollars. Each consumer who was willing to pay \(D(x_i)\) dollars (instead of \(P\) dollars) saved \(D(x_i) - P\) dollars. Hence, the total savings in the subinterval \([x_{i - 1}, x_i]\) is approximately \[(\text{savings per unit}) \, (\text{number of units}) = \parbr{D(x_i) - P} \Delta x \pd\] This product is the area of an approximating rectangle in Figure 2. Adding the savings across all \(n\) subintervals, we attain the following estimate for consumer surplus: \[s_C = \sum_{i = 1}^n \parbr{D(x_i) - P} \Delta x \pd\] This expression is a Riemann sum for the function \(D(x) - P.\) As we increase \(n,\) we sample more groups of units sold. Letting \(n \to \infty,\) \(\Delta x \to 0\) and so we attain the definite integral \begin{equation} s_C = \int_0^X \parbr{D(x) - P} \di x \pd \label{eq:s-c} \end{equation} Accordingly, the consumer surplus \(s_C\) is the area bounded under the demand curve \(p = D(x)\) and above the line \(p = P.\) (See Figure 3.)

Producer Surplus

Supply Functions A supply function \(p = S(x)\) gives the price \(p\) at which \(x\) units of a good are supplied. Whereas the Law of Demand models an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, the Law of Supply asserts that a direct relationship exists between price and quantity supplied. For example, few companies are interested in manufacturing and selling a phone for just \(\$100.\) But if the phone's market price is \($900,\) then many more companies are attracted to the market, meaning the quantity of phones supplied increases. Figure 5 shows a typical supply curve, in which \(X\) units of a good are supplied if the good is sold at \(P\) dollars.

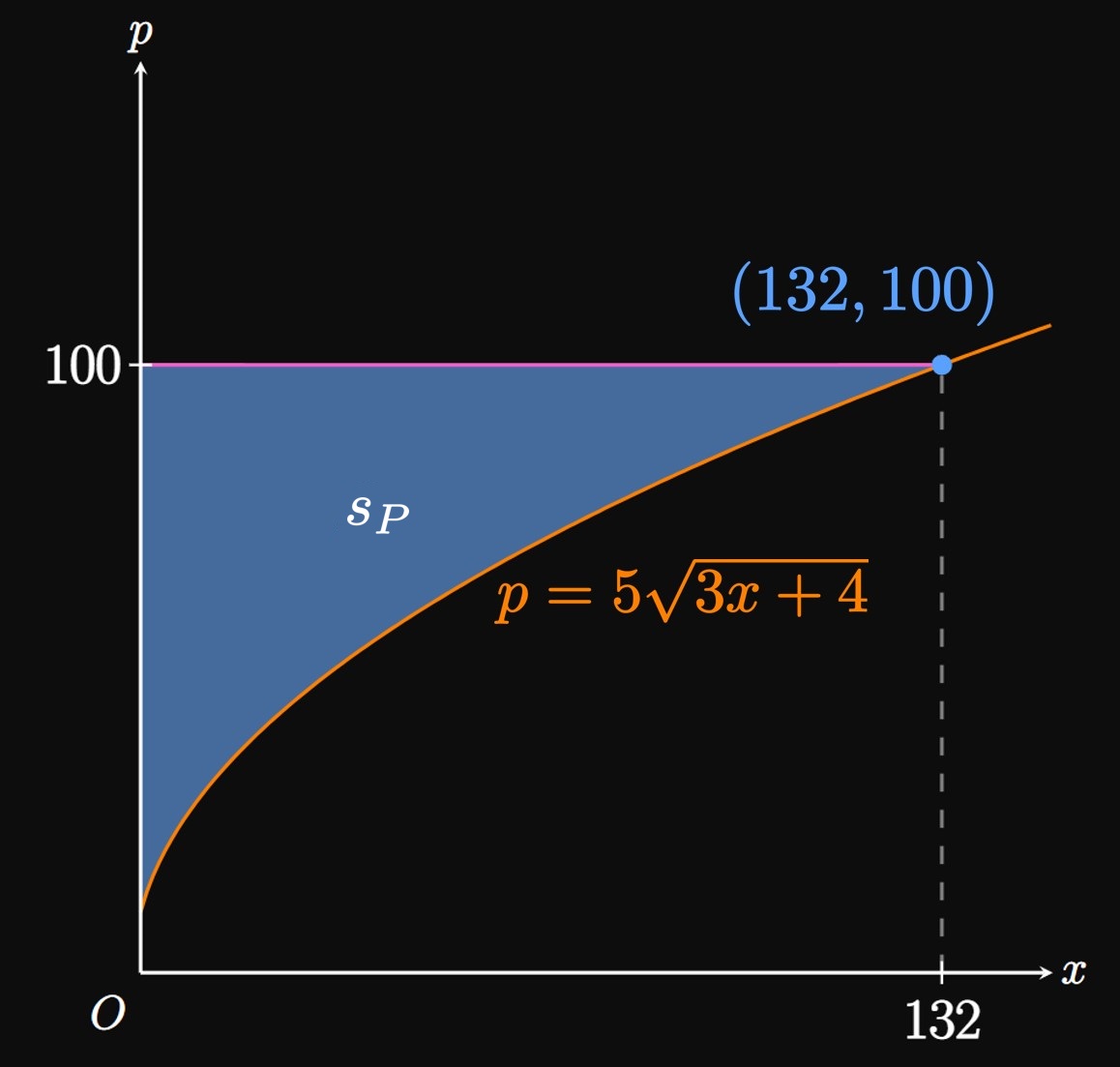

Similar to the idea in Consumer Surplus, a company may be willing to sell goods for cheaper than the market price \(P.\) Producer surplus can be interpreted as the benefit to a firm by selling units at a higher price \(P.\) We split the interval \([0, X]\) into \(n\) equally sized subintervals of size \(\Delta x = X/n.\) A firm is willing to sell \(x_{i - 1}\) units at a price of \(S(x_{i - 1})\) dollars, but will only sell \(\Delta x\) more products if the price is raised to \(S(x_{i})\) dollars. By selling the product at \(P\) dollars instead of \(S(x_{i})\) dollars, the firm gains \(P - S(x_i)\) per unit. So the firm's gain from selling \(\Delta x\) units is approximately \[(\text{gain per unit}) \, (\text{number of units}) = \parbr{P - S(x_i)} \Delta x \pd\] Let's add the gain over the \(n\) equally sized subintervals in \([0, X];\) doing so, the producer surplus is approximated by \[s_P = \sum_{i = 1}^n \parbr{P - S(x_i)} \Delta x \pd\] If we let \(n \to \infty,\) then this sum becomes the definite integral \begin{equation} s_P = \int_0^X \parbr{P - S(x)} \di x \pd \label{eq:p-surplus} \end{equation} Hence, producer surplus is the area bounded below by the supply curve and above by the line \(p = P\) (Figure 6).

Consumer Surplus We use a demand function, often a decreasing function, to model the price \(p\) at which \(x\) units of a good are demanded. Consumer surplus is a measure of total benefit to consumers by paying \(P\) dollars for a good. If \(D(x)\) is a demand function and \(P\) is an item's market price, then consumer surplus is given by \begin{equation} s_C = \int_0^X \parbr{D(x) - P} \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:s-c} \end{equation}

Producer Surplus According to the Law of Supply, a direct relationship exists between an item's market price and the number of units supplied. A supply function models the price \(p\) at which \(x\) units of a good are supplied. Producer surplus is a measure of benefit to a company by selling goods at \(P\) dollars—similar to the notion of profit. If \(S(x)\) is a supply function and \(P\) is an item's market price, then producer surplus is given by \begin{equation} s_P = \int_0^X \parbr{P - S(x)} \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:p-surplus} \end{equation}