5.5: Work

The concept of work is fundamental to physics and engineering. It measures how much energy is transferred to an object due to a force applied over some distance. As you push a pencil across a table, or as Earth pushes down on an apple as it falls, work is being done. In each case, energy is being added to an object to make it move a certain distance.

Let's suppose that an object moves along a straight line with time, as modeled by the position function \(s(t).\) Newton's Second Law states that the net force (overall force) \(F\) applied to an object equals the product of its mass \(m\) and acceleration \(a\)—namely, \begin{equation} F = ma = m \derivOrder{s}{t}{2} \pd \label{eq:newton-2} \end{equation} In the International System of Units (SI), \(m\) is measured in kilograms and \(a\) is measured in meters per second squared. Then \(F\) is expressed in kilogram-meters per second squared, a unit we define as the newton \((\text N).\) Symbolically, \(1 \un N\) \(= 1 \undiv{kg m}{sec}^2.\) The work \(W\) done by a constant force \(F\) over a distance \(d\) is defined by \begin{equation} W = Fd \pd \label{eq:work-uniform} \end{equation} So if an object is pushed harder or moved farther, then more work is done because more energy is needed for the motion. The SI unit for work is a newton-meter, which we define as the joule \((\text J).\) Or if force is measured in pounds and distance is measured in feet, then work is expressed in foot-pounds \((\text{ft·lb}).\) Work is independent of time; the time required to move an object is irrelevant to how much energy is transferred to it.

Work with Variable Forces We use \(\eqref{eq:work-uniform}\) when \(F\) is constant over the distance \(d.\) But what is the work if \(F\) isn't uniform? Let's define the object's path to be the positive \(x\)-axis from \(x = a\) to \(x = b.\) At each \(x,\) suppose that a force \(F(x)\) acts on the object. We split the interval \([a, b]\) into \(n\) subintervals of endpoints \(a = x_0,\) \(x_1, \dots,\) \(x_{n - 1}, x_n = b\) and equal width \(\Delta x.\) Assuming \(n\) is big (meaning \(\Delta x\) is small), the force \(F(x)\) is almost constant in each subinterval through which the object moves. If \(x_i^*\) is a sample point in the general subinterval \([x_{i - 1}, x_i],\) then the work done on the object over this subinterval is approximated by \(\eqref{eq:work-uniform}\) to be \[W_i \approx F \par{x_i^*} \Delta x \pd\] Hence, the total work \(W\) is approximated by summing the work done over all \(n\) subintervals: \[W \approx \sum_{i = 1}^n F \par{x_i^*} \Delta x \pd\] As we make \(n\) larger, we sample more subintervals, in each of which \(F(x)\) changes very little. If we let \(n \to \infty,\) then our sum gives the exact value of \(W\)—that is, \[W = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i = 1}^n F \par{x_i^*} \Delta x \pd\] This Riemann sum represents the integral of \(F(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b,\) so we have \begin{equation} W = \int_a^b F(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:work} \end{equation} We use this formula if the force is expressed as a function of displacement. These models are abundant in physics, as shown by the following examples.

REMARK If the force is constant, then \(\eqref{eq:work}\) becomes \[W = F \int_a^b \di x = F x \intEval_a^b = F(b - a) \cma\] where \((b - a)\) is the distance \(d\) moved. This result is a special case that agrees with \(\eqref{eq:work-uniform}.\) Accordingly, \(\eqref{eq:work}\) is the more general formula for the work done.

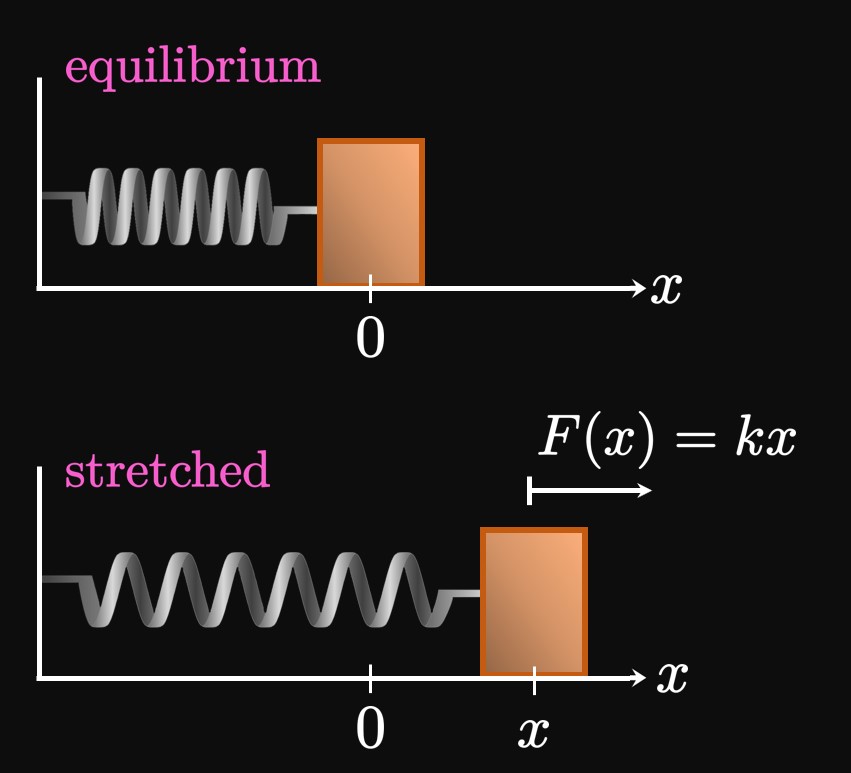

Springs

A spring's hardness is measured by the spring constant, \(k.\)

(A stiff spring has a large \(k,\) whereas a loose spring has a small

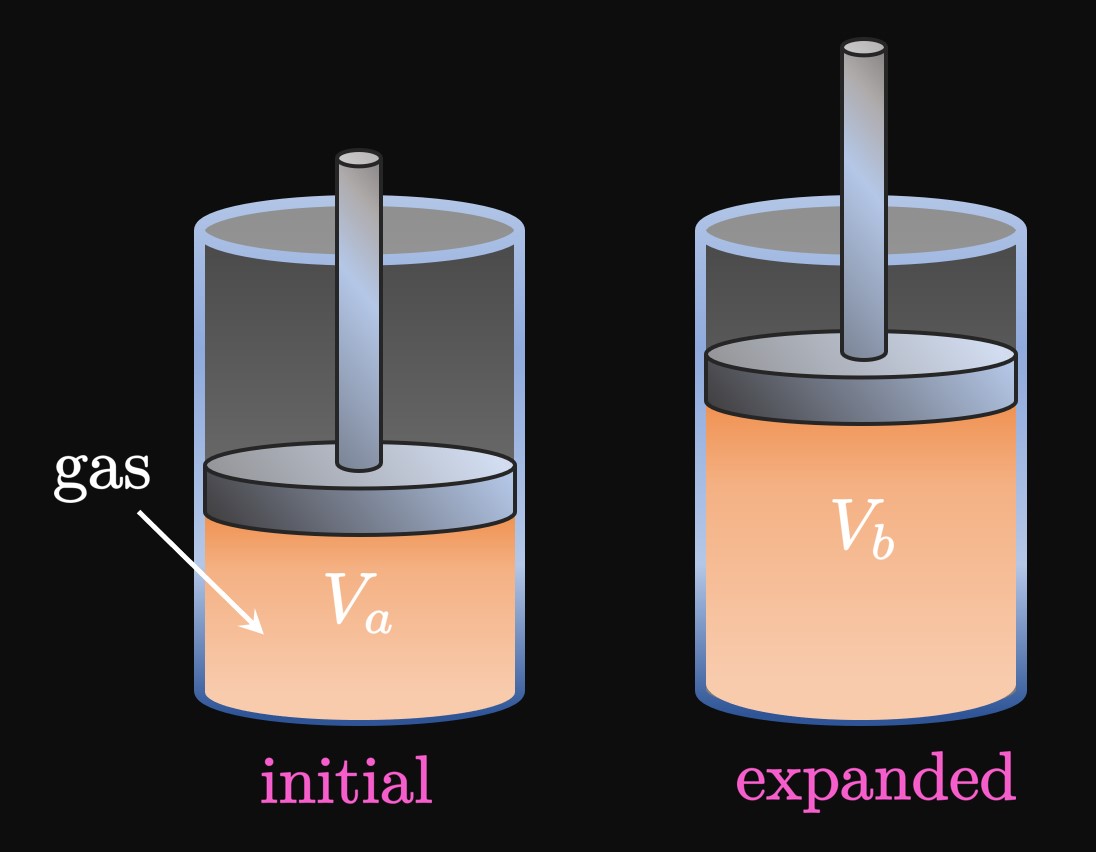

Gases A gas is a substance that expands freely and has no fixed shape. Examples of common gases are oxygen, carbon dioxide, and methane. Consider a sample of gas enclosed by a container and sealed above by a piston (Figure 2). As the gas expands in volume, the piston is pushed outward—a motion that requires work to be done by the gas. We define pressure \(P\) as force \(F\) per area \(A;\) namely, \(P = F/A.\) Boyle's Law states that a gas's pressure varies inversely with its volume \(V.\) Mathematically, if \(C\) is a constant of proportionality, then \[P = \frac{C}{V} \pd\] The gas therefore exerts a force of \[F = PA = \frac{C}{V} A \pd\] When the gas has a volume of \(V_i,\) the work done to expand the piston by a distance \(\Delta x\) is approximately \[W_i \approx F_i \Delta x = \par{\frac{C}{V_i} A} \Delta x = \frac{C}{V_i} \Delta V \pd\] Thus, the work done by the gas as its volume increases from \(V_a\) to \(V_b\) is \begin{equation} W = \int_{V_a}^{V_b} \frac{C}{V} \di V \pd \label{eq:work-gas} \end{equation}

Each portion of the cable is at a different height, meaning different amounts of work are required to lift different parts of the cable. (More work is needed to hoist the bottom part of the cable, whereas the top of the cable is closer to the building's top and therefore requires less work to raise.) It is difficult to attain a force function. When this occurs, it is a good idea to break the problem up into smaller bits. Our strategy is to consider horizontal segments of the cable and calculate the work needed to lift each one up the building. We'll then sum these works to calculate the total work \(W\) needed to lift the entire cable.

We position the \(y\)-axis to face downward

such that \(y = 0\) is the cable's top end

and \(y = 50\) is its bottom end.

(See Figure 3.)

Let's divide \([0, 50]\) into \(n\) subintervals

with endpoints \(y_0, y_1,\) \(\dots, y_n\) and equal length \(\Delta y.\)

In the general subinterval \([y_{i - 1}, y_i],\)

let \(y_i^*\) be a sample point.

All points in this subinterval are lifted up by roughly the same distance \(y_i^*.\)

Since the cable weighs \(200 \un{lb}\) and is \(50 \un{ft}\) long,

its linear density is \(200/50\) \(= 4 \undiv{lb}{ft}.\)

The weight of the

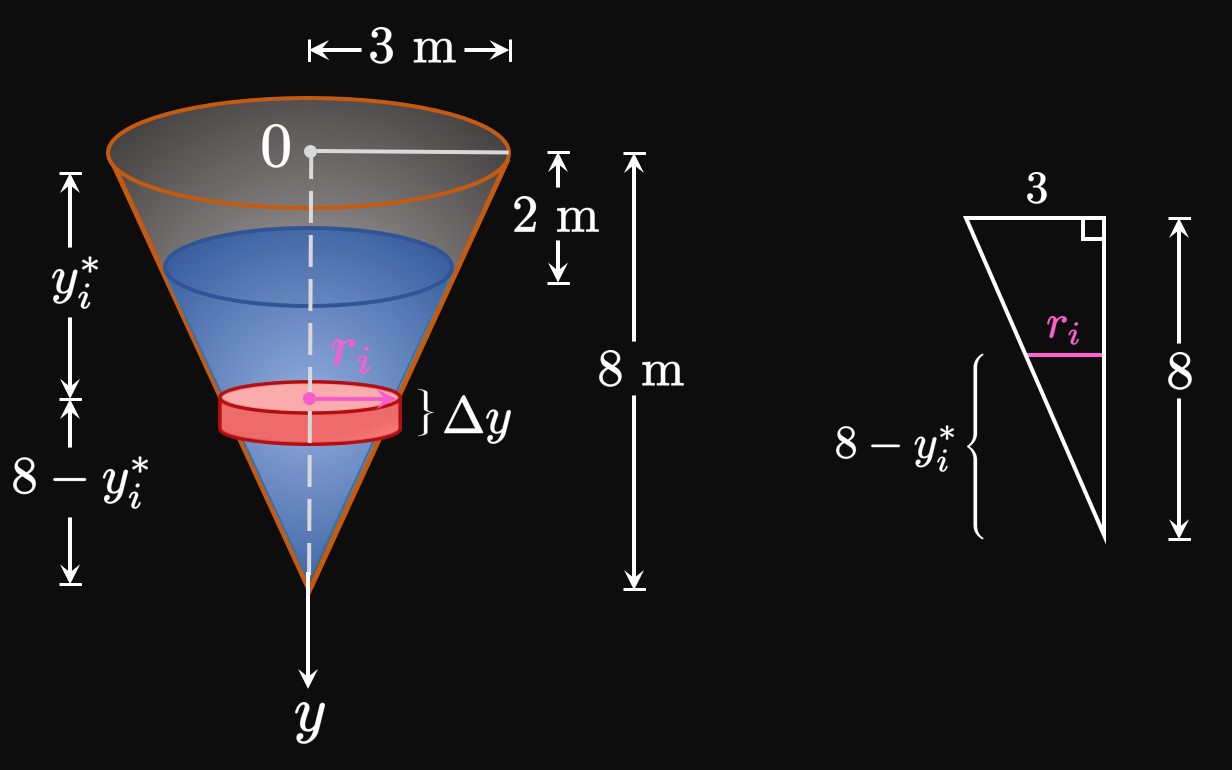

To pump all the water out, we must lift all the water to the top of the tank. But the water is scattered across different depths; the water near the top is easier to pump out than the water at the bottom. Hence, our strategy is to divide the water into layers and calculate the work needed to raise each layer to the top. We then sum these values to attain the total work \(W\) required to empty the entire tank.

Let's position the \(y\)-axis to face downward such that \(y = 0\) is the level of the cone's top.

Then the water extends from \(y = 2\) to \(y = 8.\)

We split the interval \([2, 8]\) into \(n\) subintervals

\(y_0, y_1,\) \(\dots, y_n\) and equal width \(\Delta y.\)

Let \(y_i^*\) be a sample point in the general subinterval \([y_{i - 1}, y_i].\)

Consider pumping out the \(i\)th layer, which we approximate to be a cylinder of volume

\[V_i \approx \pi r_i^2 \Delta y \pd\]

By similar triangles (Figure 4), we see

\[\frac{r_i}{8 - y_i^*} = \frac{3}{8} \so r_i = \frac{3}{8} \par{8 - y_i^*} \pd\]

Accordingly, the mass of the

Work measures how much energy is added to an object to make it move some distance. If a constant force \(F\) is applied over a distance \(d,\) then the work done is \begin{equation} W = Fd \pd \eqlabel{eq:work-uniform} \end{equation} The SI unit for work is the joule \((\text J);\) if force is measured in pounds and distance is measured in feet, then work is expressed in foot-pounds \((\text{ft·lb}).\) Work is independent of time. If a variable force \(F(x)\) acts on an object as it is moved from \(x = a\) to \(x = b,\) then the work done on the object is \begin{equation} W = \int_a^b F(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:work} \end{equation} Hooke's Law gives a force function for a spring to be \begin{equation} F(x) = kx \cma \eqlabel{eq:hooke-law} \end{equation} where \(k\) is the spring constant and \(x\) is the distance from equilibrium. A gas's pressure \(P\) and volume \(V\) are related by Boyle's Law: \[P = \frac{C}{V} \cma\] where \(C\) is a constant of proportionality. The work done by the gas as its volume increases from \(V_a\) to \(V_b\) is \begin{equation} W = \int_{V_a}^{V_b} \frac{C}{V} \di V \pd \eqlabel{eq:work-gas} \end{equation}