5.3: Solids of Revolution

In Section 5.2 we calculated volumes of solids whose cross sections were known shapes. In this section we apply such methods to calculate the volume of a solid generated by rotating a region about an axis. Many three-dimensional shapes are generated by revolution, and their volumes can be computed using integration. Therefore, we discuss the following topics:

Disk Method

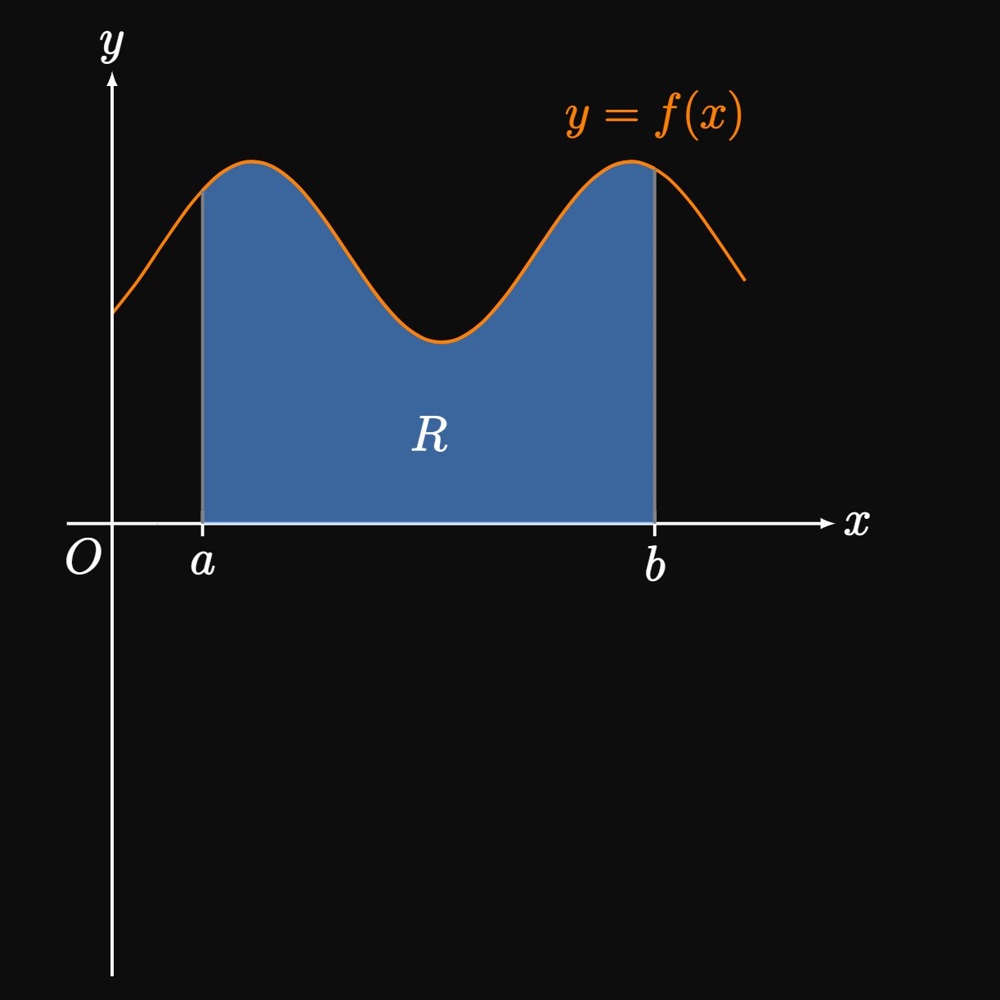

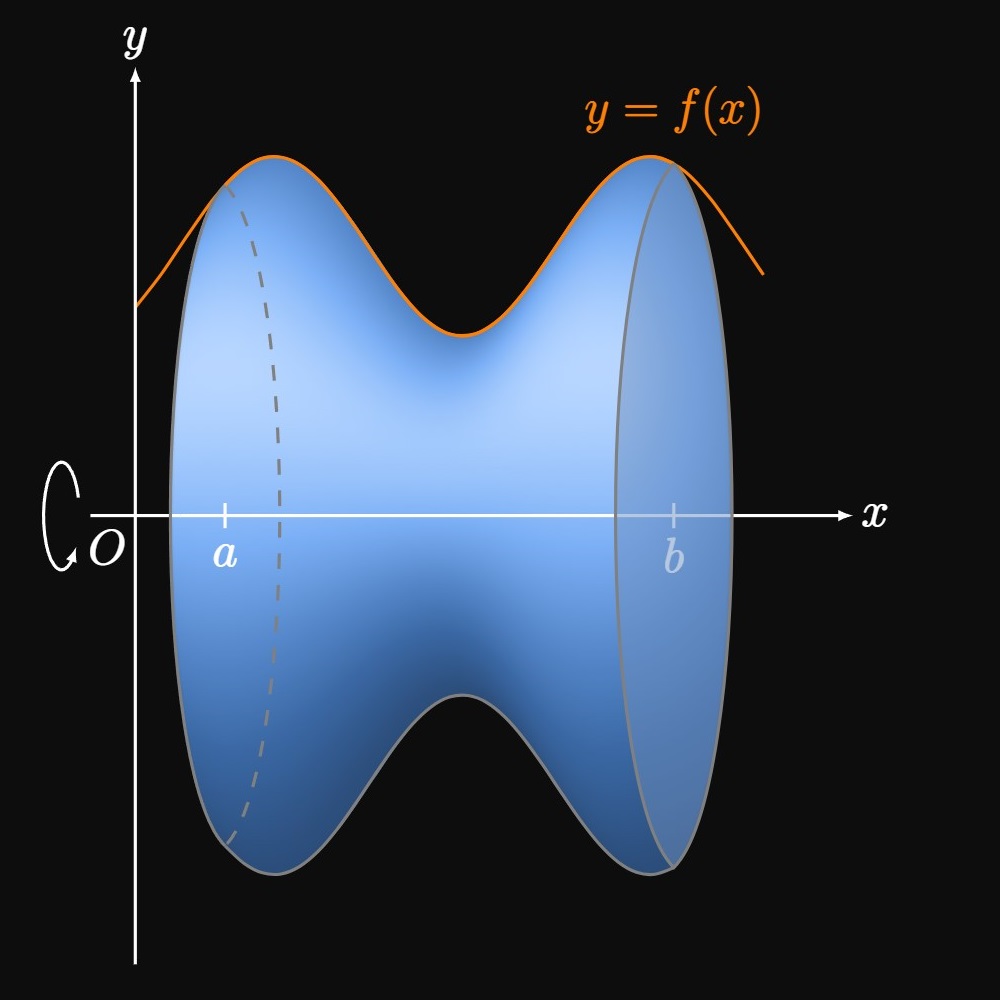

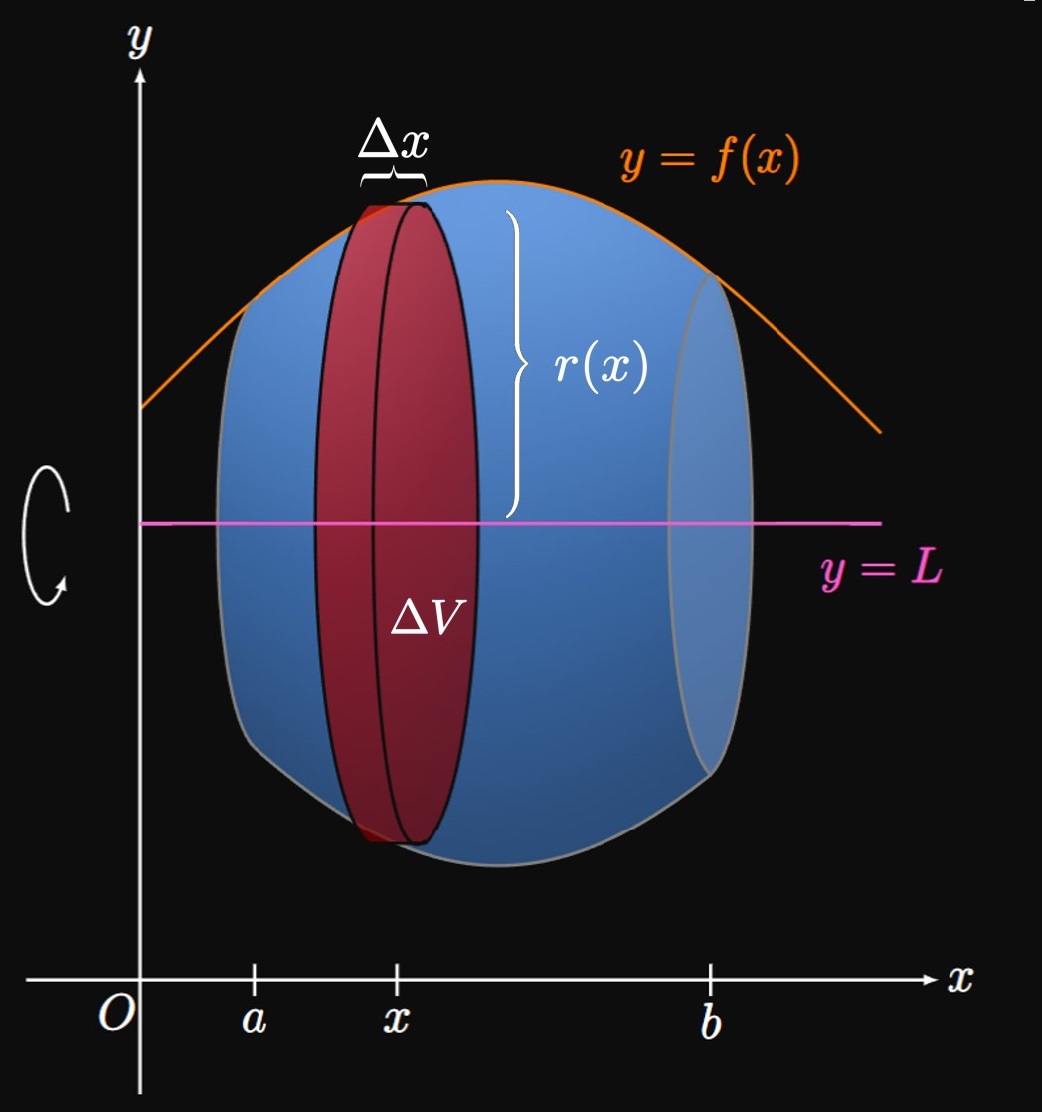

Let \(f\) be a continuous, positive function over \([a, b],\) and let \(R\) be the region under the curve \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b\) (Figure 1A). Suppose that we revolve \(R\) around the \(x\)-axis to produce a three-dimensional solid—called a solid of revolution (Figure 1B). Our objective is to calculate this solid's volume \(V.\)

Volume Calculation

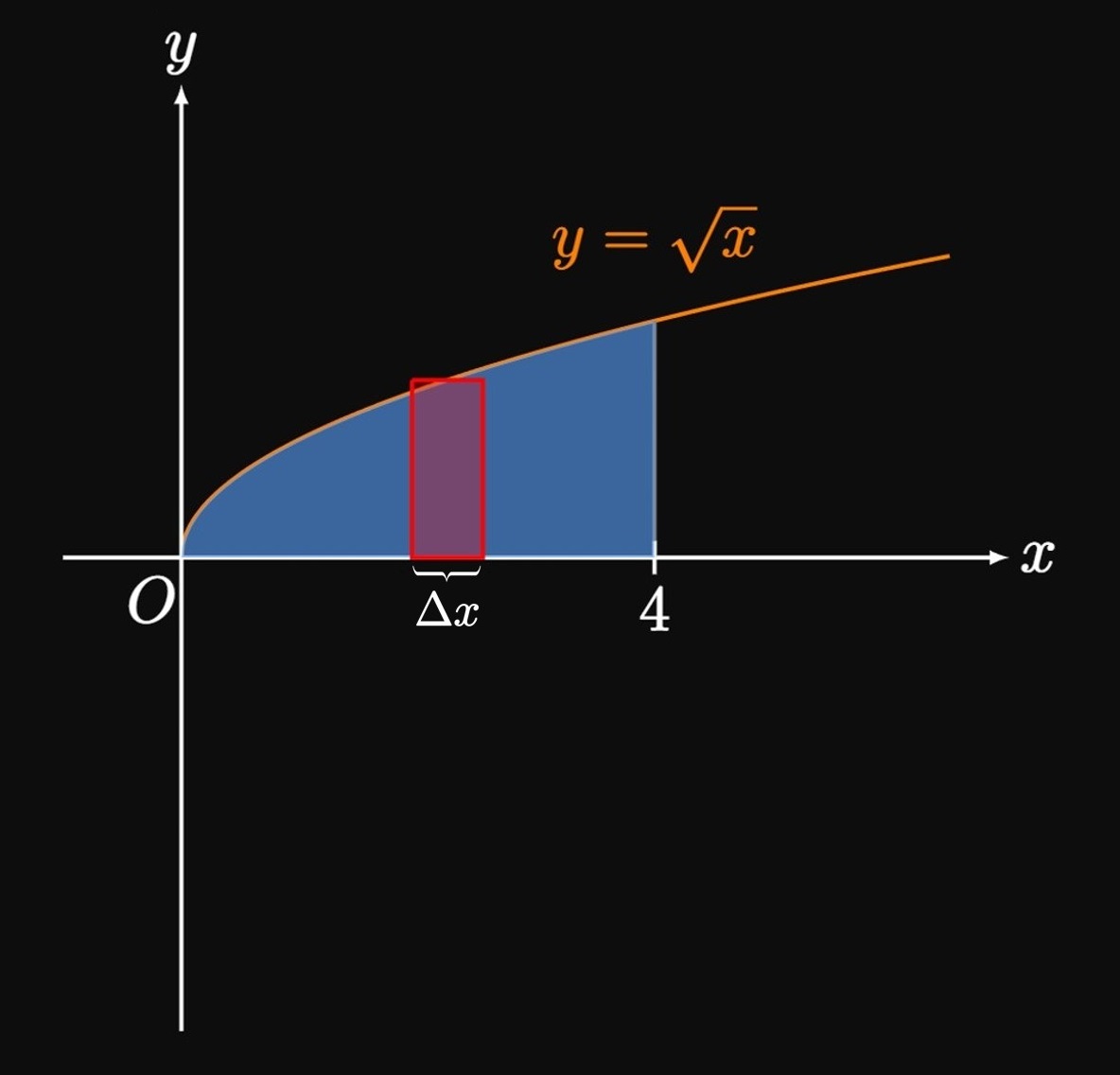

We cut the region \(R\) into \(n\) equal-width rectangles and rotate them about the \(x\)-axis.

The \(n\) subintervals in \([a, b]\) have endpoints \(a = x_0,\) \(x_1, \dots,\) \(x_{n - 1}, x_n = b.\)

Consider the point \(x_i^*\) in some subinterval \([x_{i - 1}, x_i].\)

An approximating rectangle in this subinterval therefore has base \(\Delta x = (b - a)/n\)

and height \(f(x_i^*)\)

(Figure 2).

If we rotate this rectangle about the \(x\)-axis,

then we obtain a cylinder—resembling a disk—of depth

\(\Delta x\) and radius \(f(x_i^*).\)

At \(x = x_i^*\) the cylinder's cross section perpendicular to the \(x\)-axis is a circle

of radius \(f(x_i^*);\) its area is therefore \(A(x_i^*) = \pi [f(x_i^*)]^2.\)

So the approximating cylinder's volume is

\[\Delta V = A \par{x_i^*} \Delta x = \pi [f(x_i^*)]^2 \Delta x \pd\]

(See Figure 3.)

Therefore, to approximate the entire volume \(V\) of the solid of revolution,

we rotate all \(n\) rectangles about the \(x\)-axis

and compute the sum of their volumes:

\[V \approx \sum_{i = 1}^n \pi [f(x_i^*)]^2 \Delta x \pd\]

If we let \(n \to \infty,\) then \(\Delta x \to 0\)

and so we inscribe infinitely many thin rectangles in region \(R.\)

Accordingly, the depth \(\Delta x\) of the disks shrinks to \(0.\)

We therefore assert that \(V\) is the limiting value of the sum

as \(n \to \infty \col\)

\[V = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i = 1}^n \pi [f(x_i^*)]^2 \Delta x \pd\]

(A visual representation of this limit is shown in Animation 1.)

This form is a Riemann sum for the function \(\pi [f(x)]^2,\)

so we see

\begin{equation}

V = \pi \int_a^b [f(x)]^2 \di x \pd \label{eq:disk-x}

\end{equation}

Because each approximating cylinder is a disk shape,

the use of \(\eqref{eq:disk-x}\) is called the Disk Method.

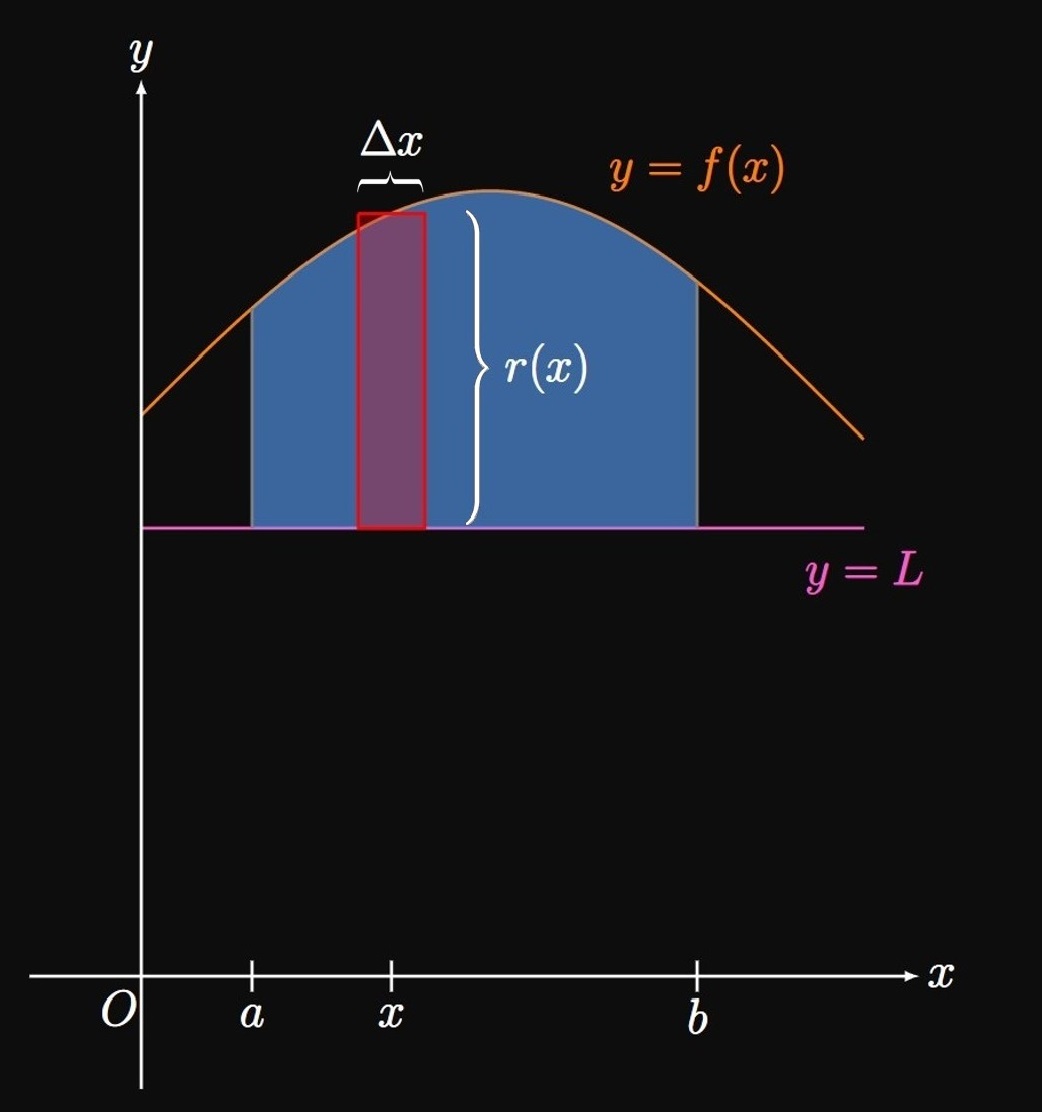

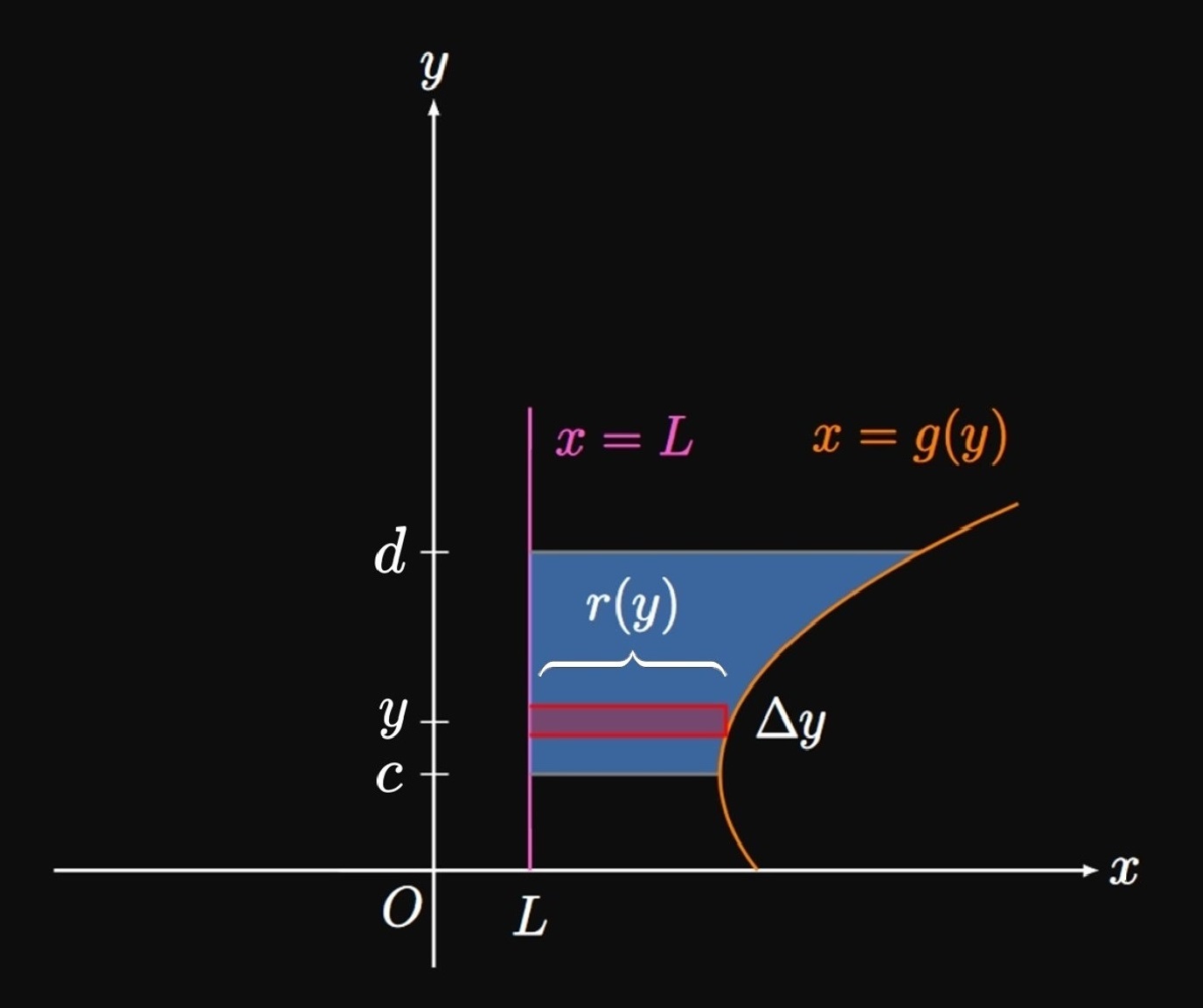

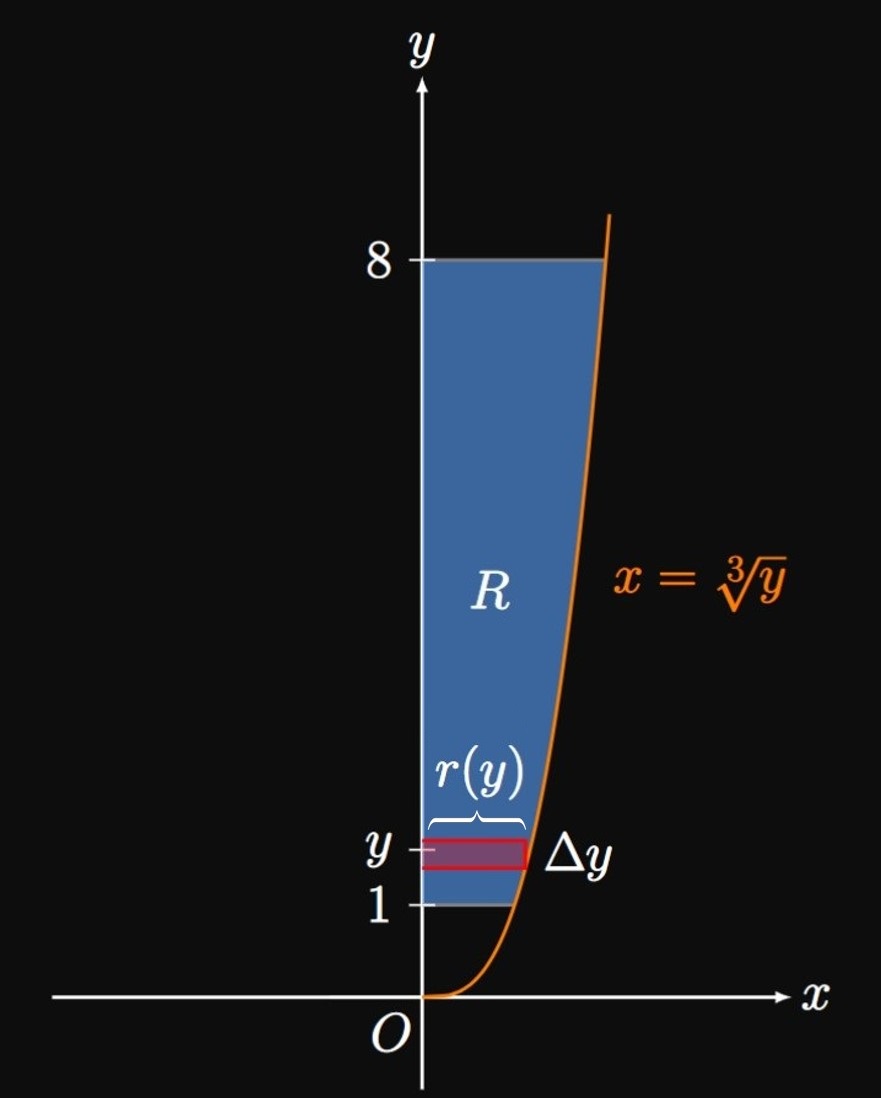

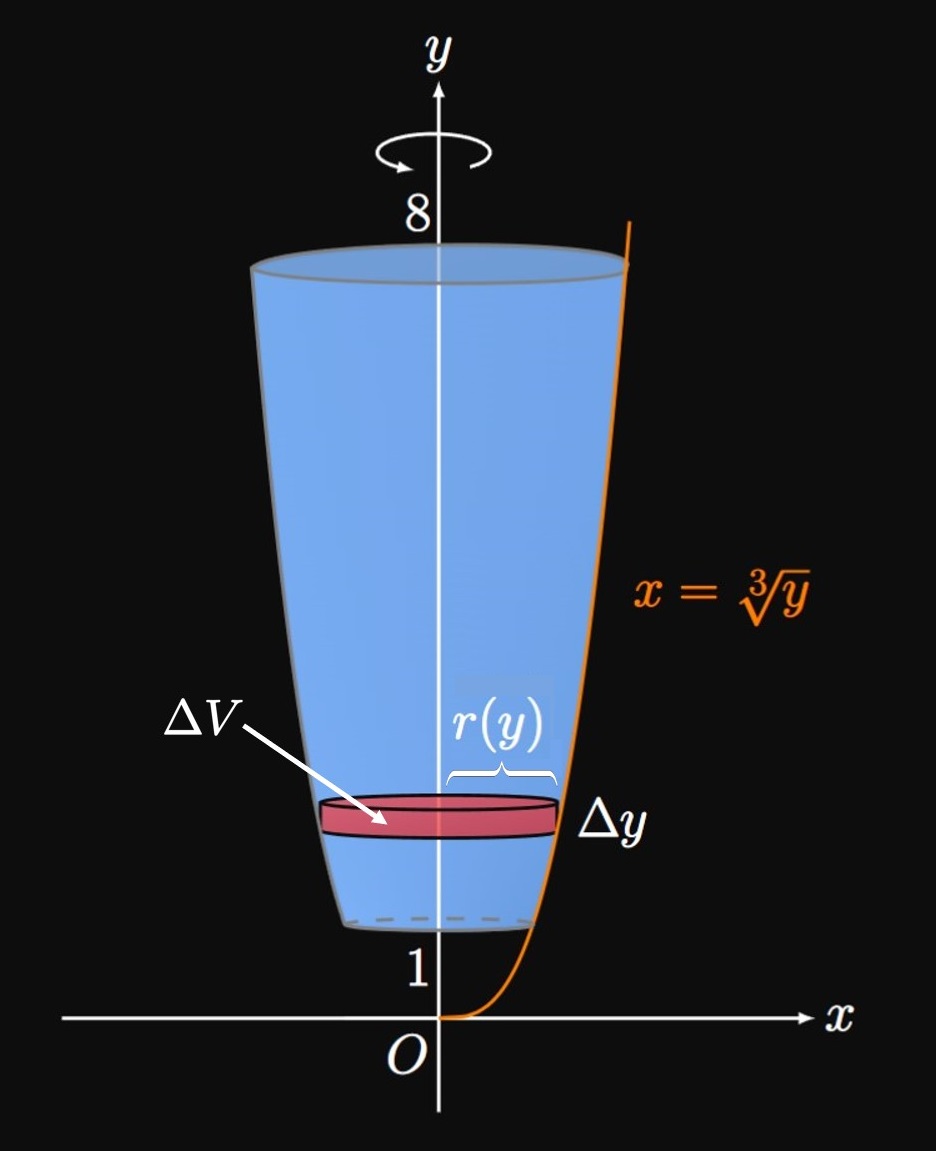

Disk Method with Other Axes Many solids of revolution are created by other axes of rotation—for example, by revolution of a region around some horizontal line \(y = L.\) Consider a region bounded by the curve \(y = f(x)\) and the line \(y = L\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b.\) Let \(r(x)\) be the distance from the function \(y = f(x)\) to the line \(y = L,\) as shown by an approximating rectangle of width \(\Delta x\) in Figure 6A. Then at some \(x,\) an approximating disk's radius is \(r(x)\) and so its volume is \[\Delta V = \pi [r(x)]^2 \Delta x \pd\] (See Figure 6B.) So the total volume \(V\) of the generated solid of revolution is \begin{equation} V = \pi \int_a^b [r(x)]^2 \di x \pd \label{eq:disk-r} \end{equation} We can also rotate regions about a vertical axis of revolution. In Figure 7A, a region is enclosed between the curve \(x = g(y),\) the vertical line \(x = L,\) and the lines \(y = c\) and \(y = d.\) At any \(y,\) an approximating rectangle in this region has base \(r(y)\) and height \(\Delta y.\) Thus, if we rotate the enclosed region about the line \(x = L,\) then an approximating disk has volume \[\Delta V = \pi [r(y)]^2 \Delta y \pd\] The total volume \(V\) of the solid is therefore \begin{equation} V = \pi \int_c^d [r(y)]^2 \di y \pd \label{eq:disk-r-y} \end{equation} (See Figure 7B.) Using \(\eqref{eq:disk-r}\) and \(\eqref{eq:disk-r-y},\) we're able to calculate the volumes of solids of revolution generated by revolving any region around a line that bounds the enclosed region.

Washer Method

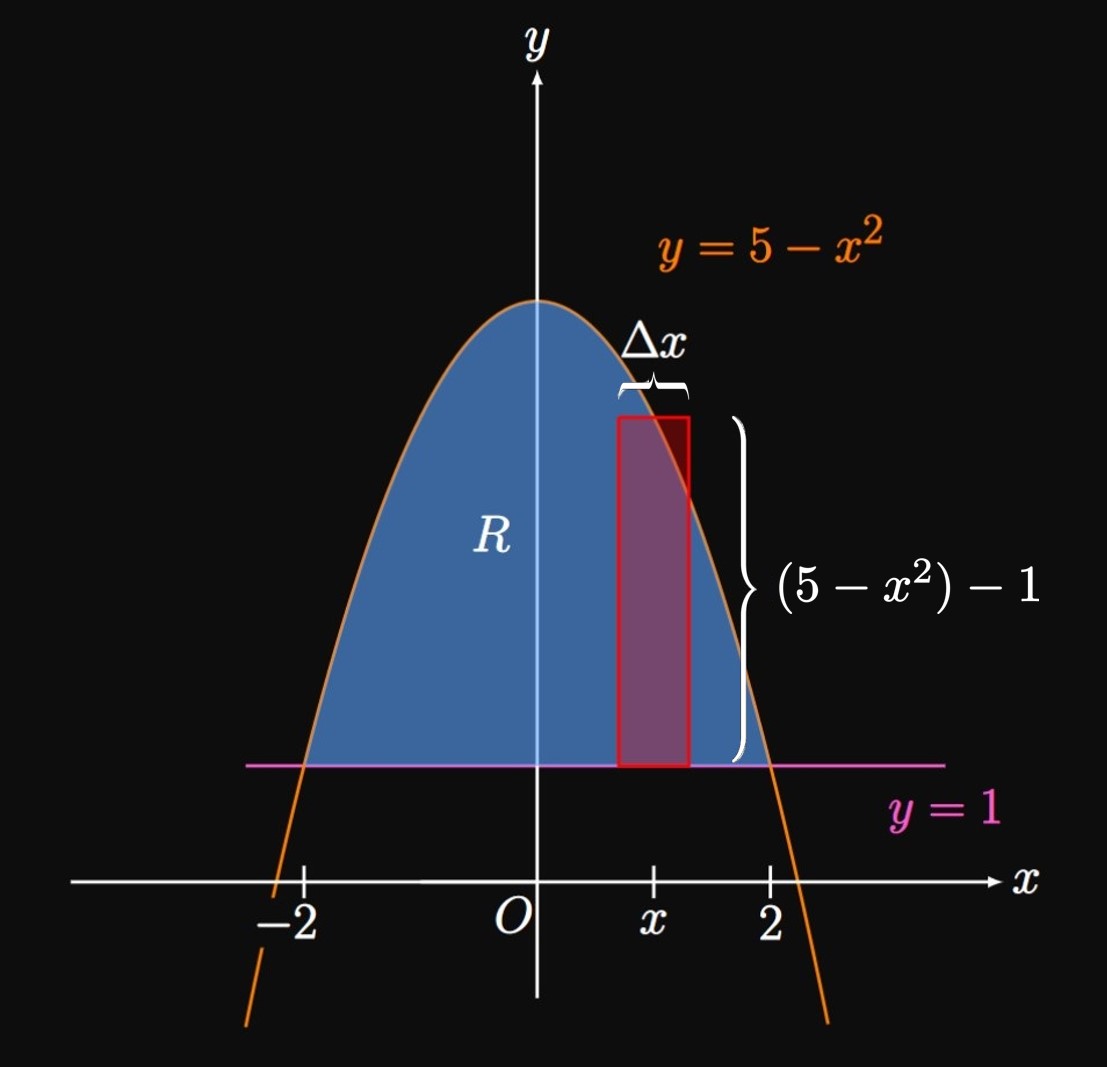

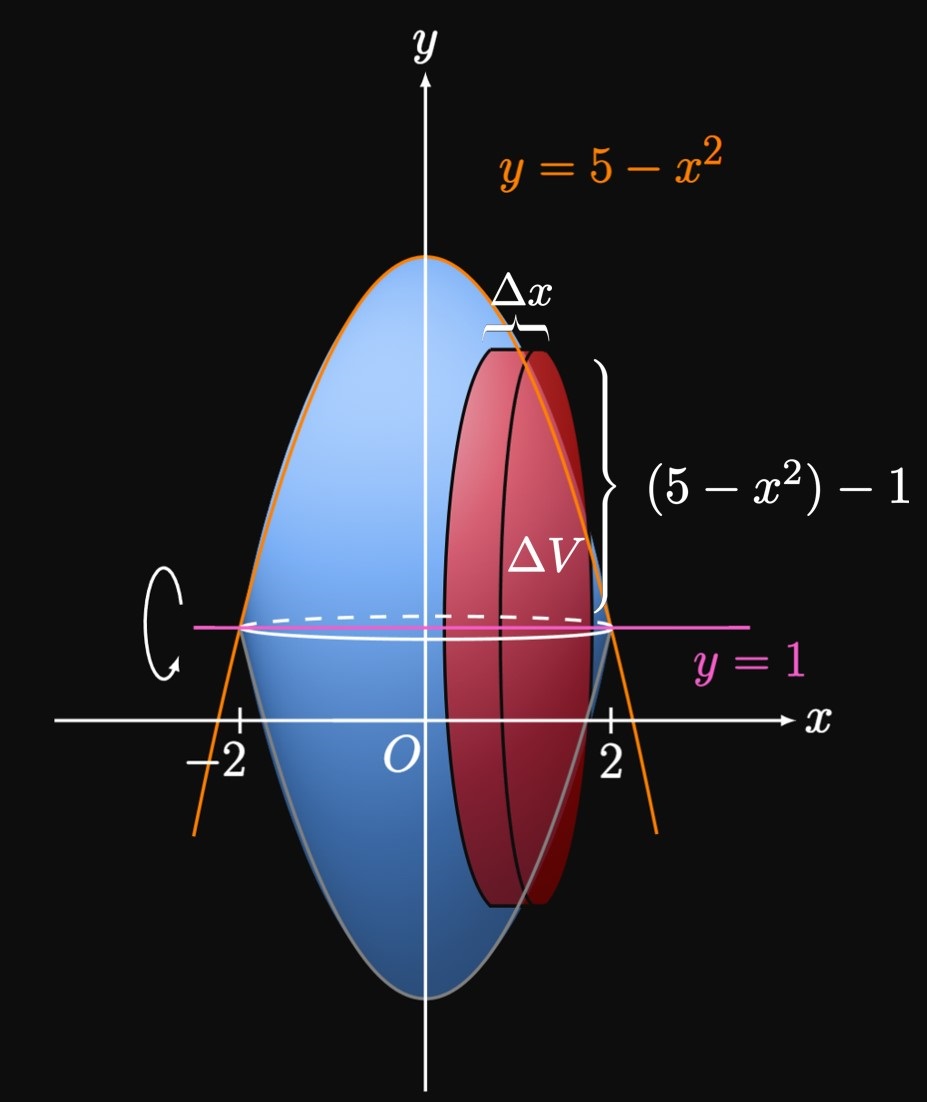

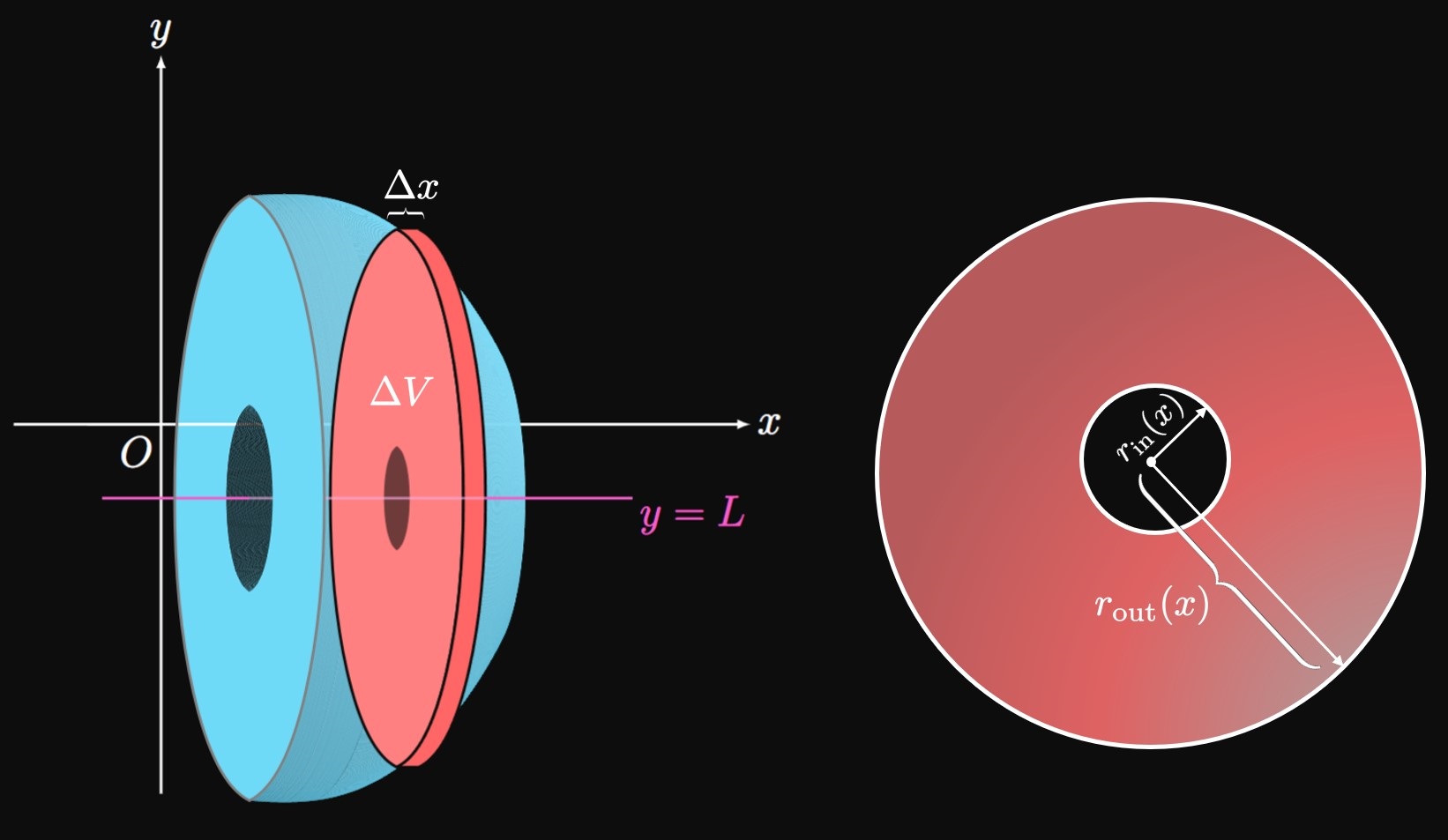

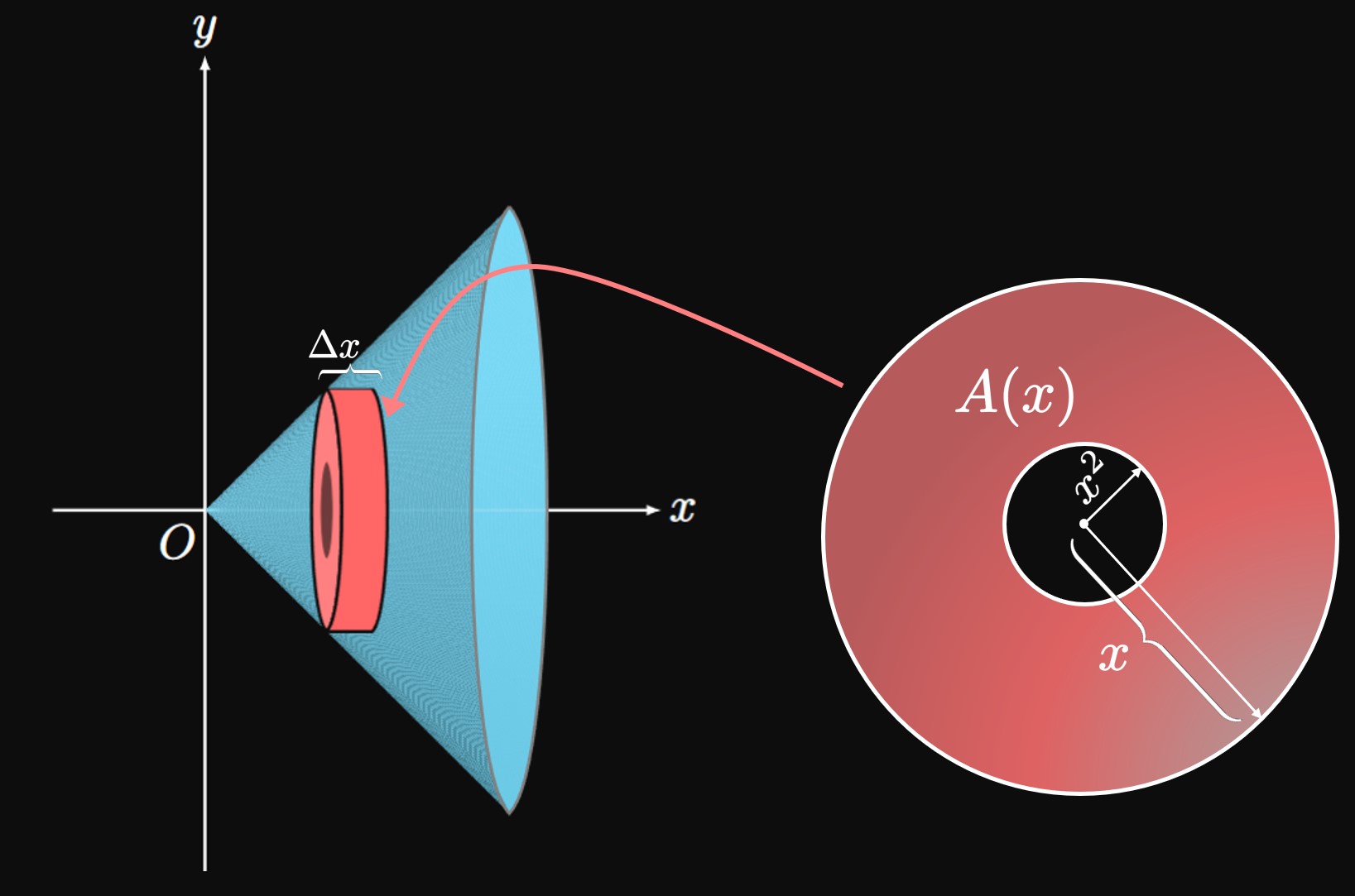

We use the Disk Method when there is no gap between a region and the axis of revolution. But when the axis of revolution doesn't lie adjacent to the region, we use the Washer Method. In Figure 12, consider the region enclosed by the curves \(y = f(x)\) and \(y = g(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b.\) At \(x\) we have drawn an approximating rectangle of width \(\Delta x.\) From the line \(y = L,\) the distance to the top of this rectangle is \(\out r(x)\) and the distance to the bottom of the rectangle is \(\inn r(x).\) Upon rotating this rectangle about the line \(y = L,\) we attain a washer—a disk with a hollow center. A washer's cross-sectional area is therefore given by subtracting the area of the inner circle from the area of the outer circle. The outer circle has radius \(\out r(x),\) and the inner circle has radius \(\inn r(x).\) So its area is \[A(x) = \pi \parbr{\out r(x)}^2 - \pi \parbr{\inn r(x)}^2 \pd\] An approximating washer shown in Figure 13 therefore has volume \[\Delta V = \pi \par{\parbr{\out r(x)}^2 - \parbr{\inn r(x)}^2} \Delta x \pd\] The entire volume \(V\) of the solid is therefore given by integrating \(A(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b,\) from which we get \begin{equation} V = \pi \int_a^b \par{\parbr{\out r(x)}^2 - \parbr{\inn r(x)}^2} \di x \pd \label{eq:washer-x} \end{equation} Note that the integral \(\pi \int_a^b \parbr{\inn r(x)}^2 \di x\) is the volume of the hole in the solid, which we subtracted from the volume involving the outer radius.

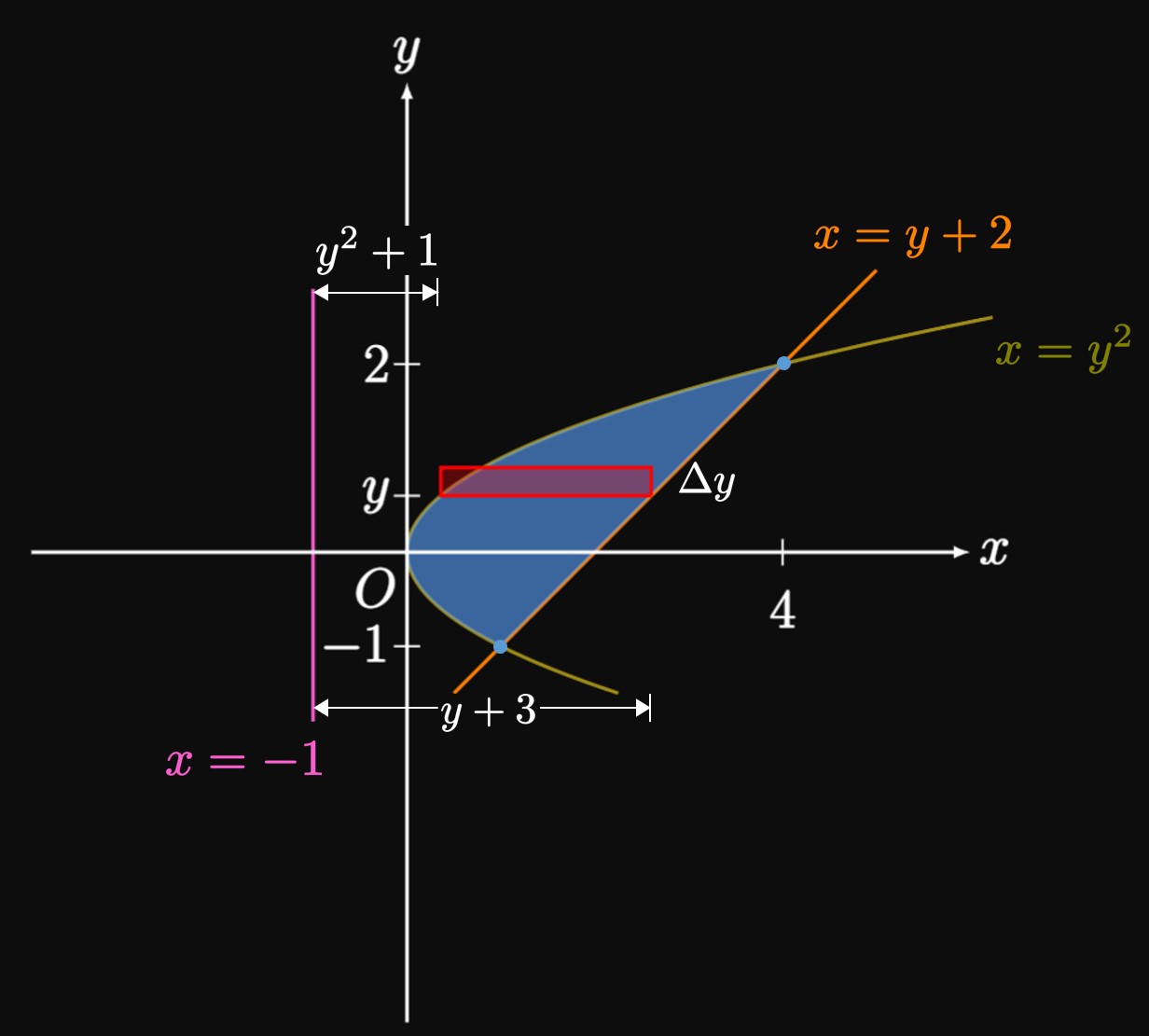

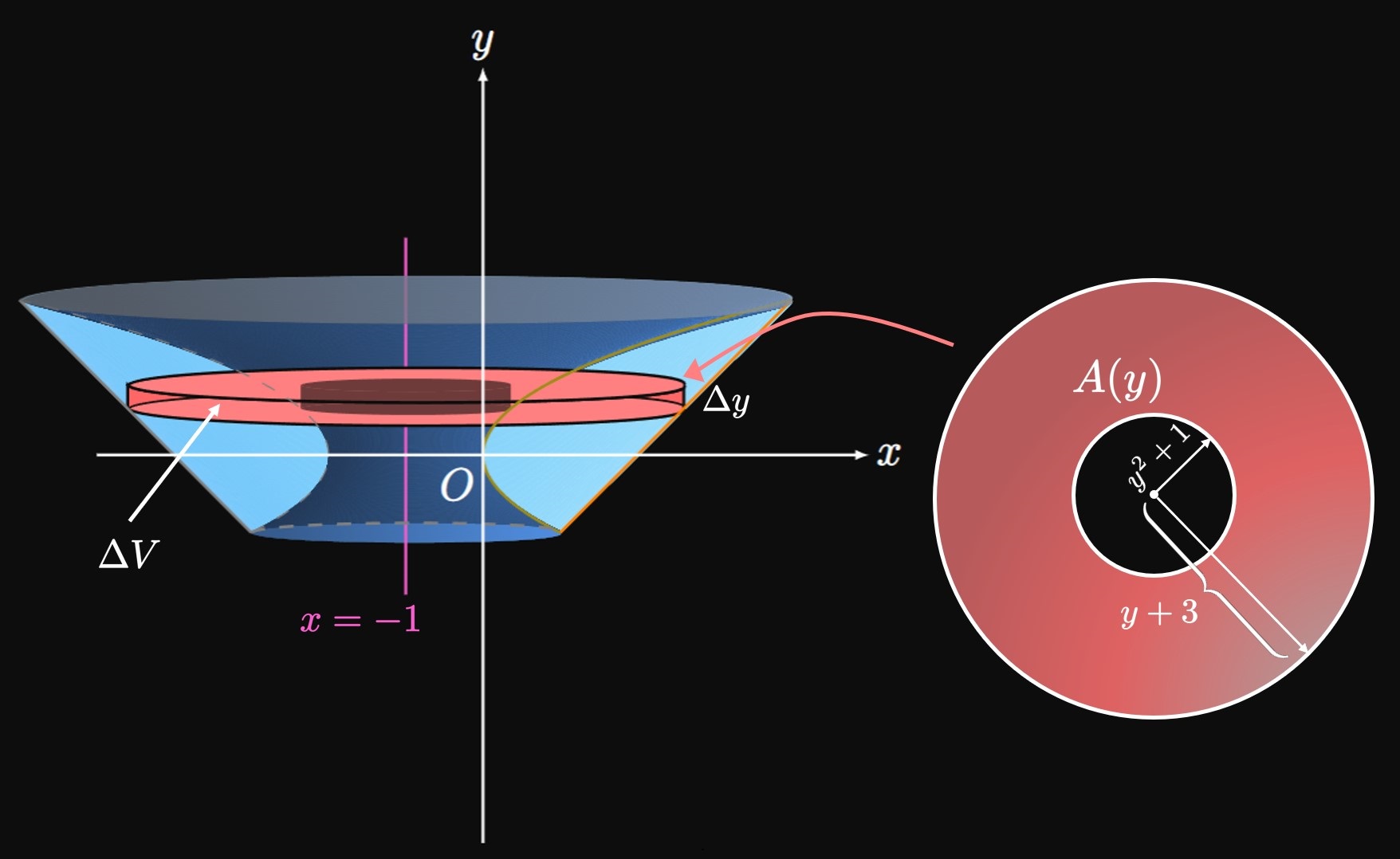

Using the same logic, if we can determine expressions for \(\out r(y)\) and \(\inn r(y),\) then we can compute the volume of a solid formed by rotating a region bounded between \(y = c\) and \(y = d\) about a vertical line. We employ a nearly identical formula to \(\eqref{eq:washer-x}\)—namely, \begin{equation} V = \pi \int_c^d \par{\parbr{\out r(y)}^2 - \parbr{\inn r(y)}^2} \di y \pd \label{eq:washer-y} \end{equation}

CAUTION The volume of a solid of revolution can never be negative. Hence, \(\eqref{eq:washer-x}\) and \(\eqref{eq:washer-y}\) should never return negative values, regardless of the quadrant in which the region or solid lies. Note that the integrand is \(\out r^2 - \inn r^2,\) not \(\par{\out r - \inn r}^2.\) In other words, we integrate a difference of squares, not the square of a difference.

We now develop a list of steps that enable us to calculate the volume of a solid formed by rotating a region \(R\) about a horizontal line or about a vertical line. Generally, in the former case we integrate with respect to \(x,\) whereas in the latter case we integrate with respect to \(y.\)

- Sketch the bounded region \(R\) and calculate the points of intersection \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\) Draw a vertical approximating rectangle.

- At any \(x,\) determine the distance \(\inn r(x)\) from \(y = L\) to the rectangle's closest horizontal side. Then find the distance \(\out r(x)\) from \(y = L\) to the rectangle's farthest horizontal side.

- Use \(\eqref{eq:washer-x}\) with the bounds \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\)

- Sketch the bounded region \(R\) and calculate the points of intersection \(y = c\) and \(y = d.\) Draw a horizontal approximating rectangle.

- At any \(y,\) determine the distance \(\inn r(y)\) from \(x = L\) to the rectangle's closest vertical side. Then find the distance \(\out r(y)\) from \(x = L\) to the rectangle's farthest vertical side.

- Use \(\eqref{eq:washer-y}\) with the bounds \(y = c\) and \(y = d.\)

Disk Method We use the Disk Method to compute the volume of a solid of revolution generated by rotating a region about a line. This method is only applicable if there is no gap between the region and the line about which we rotate the region. Let \(f\) be a positive, continuous function on \([a, b].\) The volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded by \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b\) about the \(x\)-axis is given by \begin{equation} V = \pi \int_a^b [f(x)]^2 \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:disk-x} \end{equation} More generally, let function \(r\) be the distance from the axis of revolution (the line around which we revolve a region) to a point on the graph. We use the Disk Method through the following formulas: \begin{alignat}{2} V &= \pi \int_a^b [r(x)]^2 \di x \cma \lspace &&[\textrm{Horizontal Axis of Revolution}] \eqlabel{eq:disk-r} \nl V &= \pi \int_c^d [r(y)]^2 \di y \pd \lspace &&[\textrm{Vertical Axis of Revolution}] \eqlabel{eq:disk-r-y} \nl \end{alignat}

Washer Method If a gap exists between an enclosed region and the axis of revolution, then the Washer Method permits us to calculate the volume of the solid of revolution. If \(\out r\) is the outer distance from the axis of revolution and \(\inn r\) is the inner distance from the axis of revolution, then we use the Washer Method through the following formulas: \begin{alignat}{2} V &= \pi \int_a^b \par{\parbr{\out r(x)}^2 - \parbr{\inn r(x)}^2} \di x \cma \lspace &&[\textrm{Horizontal Axis of Revolution}] \eqlabel{eq:washer-x} \nl V &= \pi \int_c^d \par{\parbr{\out r(y)}^2 - \parbr{\inn r(y)}^2} \di y \pd \lspace &&[\textrm{Vertical Axis of Revolution}] \eqlabel{eq:washer-y} \nl \end{alignat} If region \(R\) is bounded between two functions \(y = f(x)\) and \(y = g(x),\) then the following steps enable you to calculate the volume of the solid of revolution generated by rotating \(R\) about a horizontal line \(y = L \col\)

- Sketch the bounded region \(R\) and calculate the points of intersection \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\) Draw a vertical approximating rectangle.

- At any \(x,\) determine the distance \(\inn r(x)\) from \(y = L\) to the rectangle's closest horizontal side. Then find the distance \(\out r(x)\) from \(y = L\) to the rectangle's farthest horizontal side.

- Use \(\eqref{eq:washer-x}\) with the bounds \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\)

If region \(R\) is bounded between two functions \(x = f(y)\) and \(x = g(y),\) then the following steps enable you to calculate the volume of the solid of revolution generated by rotating \(R\) about a vertical line \(x = L \col\)

- Sketch the bounded region \(R\) and calculate the points of intersection \(y = c\) and \(y = d.\) Draw a horizontal approximating rectangle.

- At any \(y,\) determine the distance \(\inn r(y)\) from \(x = L\) to the rectangle's closest vertical side. Then find the distance \(\out r(y)\) from \(x = L\) to the rectangle's farthest vertical side.

- Use \(\eqref{eq:washer-y}\) with the bounds \(y = c\) and \(y = d.\)