3.8: Newton's Method

Whereas quadratic equations \(ax^2 + bx + c = 0\) have solutions given by the Quadratic Formula, other types of functions lack such a well-known formula (or any formula at all). How do we approximate the zeros of such a function? In this section we present Newton's Method, in which we use successive tangent lines to estimate the roots of functions.

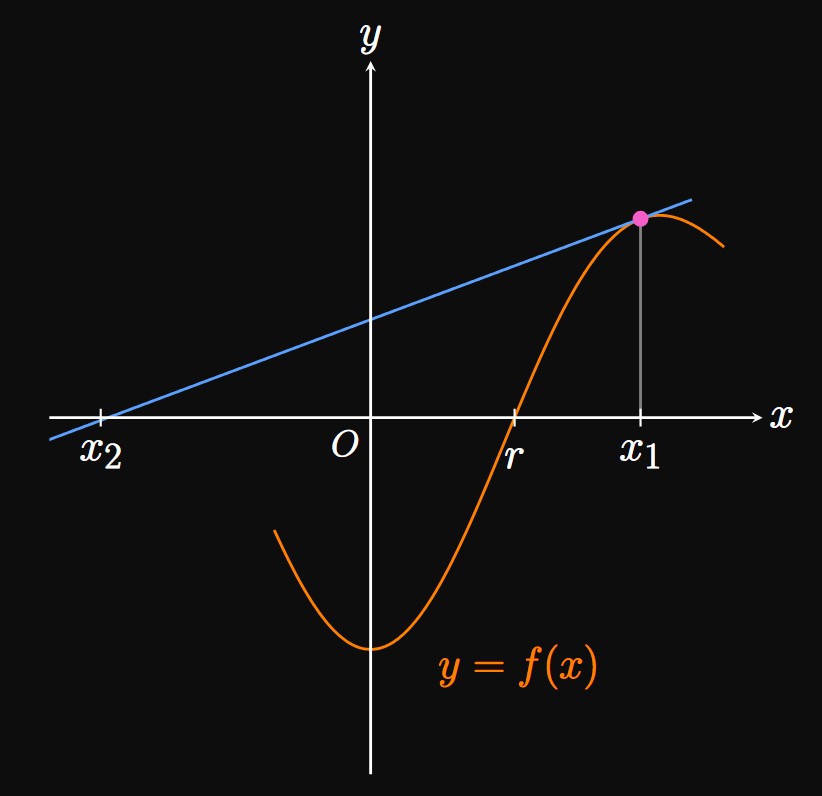

Suppose that a function \(f\) is differentiable on some interval containing a root \(r.\)

Our goal is to estimate the value of \(r\) in the equation \(f(r) = 0.\)

We first approximate the root to be some value \(x_1;\)

then we construct a tangent line \(\ell_1\) to \(f\) at \((x_1, f(x_1)).\)

The idea of Newton's Method is to approximate the curve's \(x\)-intercept

to be the tangent line's \(x\)-intercept, denoted \(x_2.\)

(Since \(\ell_1\) is a line, its \(x\)-intercept is simple to calculate.)

An equation of \(\ell_1\) is, by point-slope form,

\[y - f(x_1) = f'(x_1)(x - x_1) \pd\]

The coordinates of the \(x\)-intercept are \((x_2, 0),\)

which we substitute to get

\[

\ba

0 - f(x_1) &= f'(x_1) (x_2 - x_1) \nl

\implies x_2 &= x_1 - \frac{f(x_1)}{f'(x_1)} \cma

\ea

\]

assuming \(f'(x_1) \ne 0.\)

Thus, \(x_2\) is the next (usually more accurate) approximation of the root \(r.\)

(See Figure 1.)

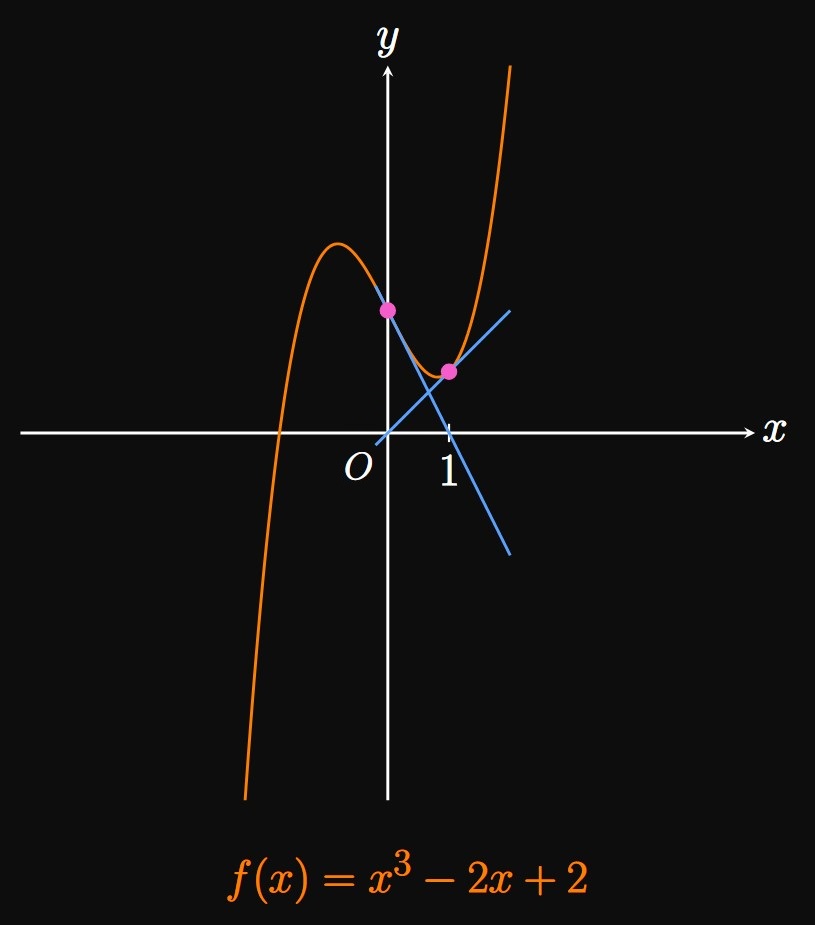

Again, at \((x_2, f(x_2))\)

we construct another tangent line \(\ell_2\) to \(f,\)

whose \(x\)-intercept \(x_3\) is (usually) a better estimate of \(r.\)

An equation of \(\ell_2\) is

\[y - f(x_2) = f'(x_2) (x - x_2) \pd\]

Substituting \((x_3, 0)\) produces

\[

\ba

0 - f(x_2) &= f'(x_2) (x_3 - x_2) \nl

\implies x_3 &= x_2 - \frac{f(x_2)}{f'(x_2)} \pd

\ea

\]

By repeating this process,

we usually attain increasingly accurate approximations of \(r.\)

In general, if the

\(\eqrefer{eq:newton-n}\) represents an iterative process because we use the same rule to attain \(x_{n + 1}\) from \(x_n.\) (Each application of Newton's Method is called an iteration.) Thus, it is easy to write a computer script or calculator program to execute Newton's Method.

To estimate a root to a desired accuracy threshold, we generally cease using Newton's Method if \(x_n\) and \(x_{n + 1}\) agree to the same desired number of decimal places. (It is unlikely that further iterations will change the approximation significantly.) The following example demonstrates this idea.

Failure

Unfortunately, Newton's Method does not always work.

If the approximations \(x_1,\) \(x_2, \dots\)

do not converge to \(r,\)

then Newton's Method is said to fail.

Obviously, if \(f'(x_n) = 0\) and \(f(x_n) \ne 0,\)

then Newton's Method is invalid because the tangent line does not cross the \(x\)-axis.

Newton's Method may also fail if a function has multiple roots,

since successive iterations may converge to a different root than the desired root.

Generally, the method fails or converges very slowly if we pick \(x_1\)

such that \(f'(x_1)\) is close to \(0.\)

In any of these cases, we should select a better starting approximation \(x_1.\)

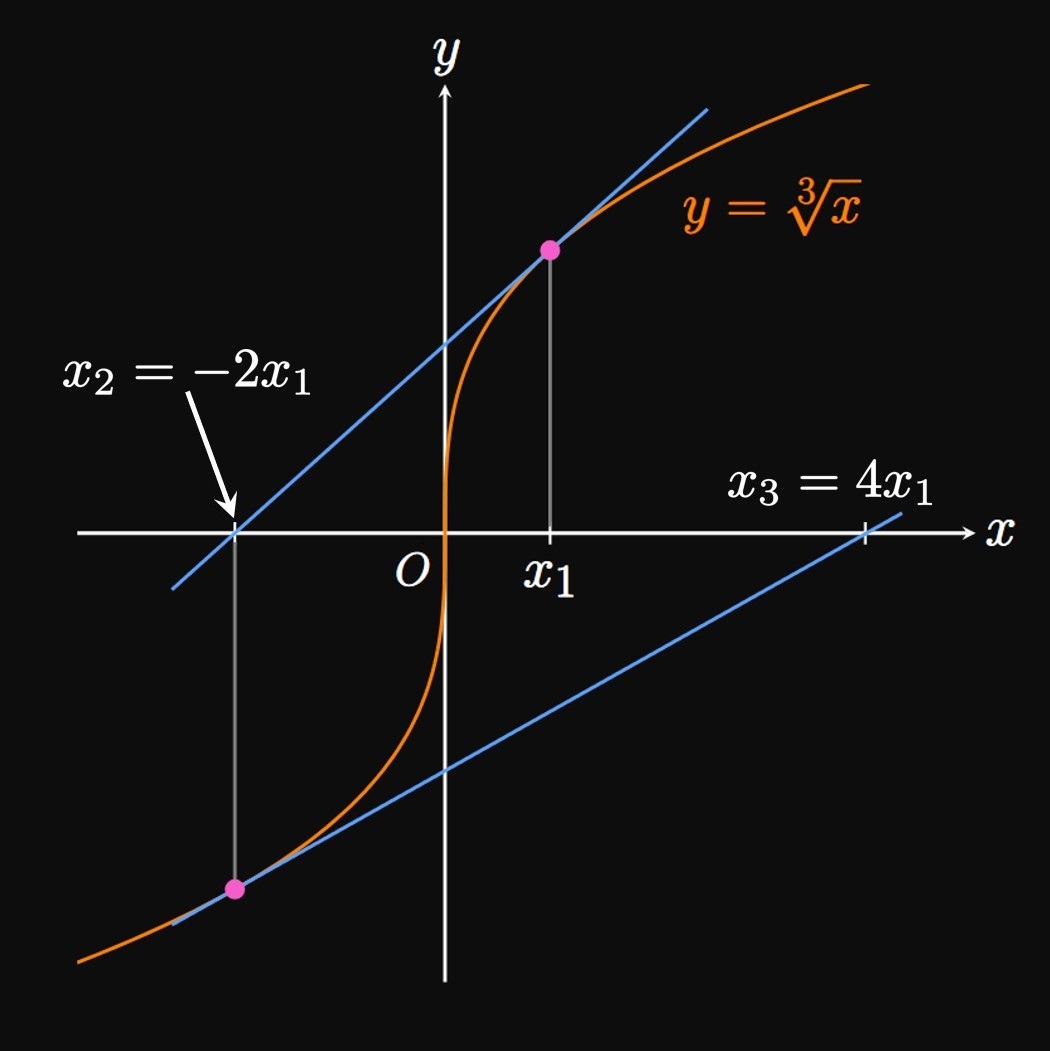

In Figure 3

the choice of \(x_1\) makes \(f'(x_1)\) close to \(0,\)

so the tangent line has a large range and therefore poorly models the behavior of \(f.\)

Accordingly, \(x_2\) is a worse approximation than \(x_1\) in estimating the root \(r.\)

(In fact, \(x_2\) is such a poor approximation that it falls outside the domain of

Newton's Method enables us to approximate a root of a function by using successive tangent lines, an iterative process. If \(f\) is differentiable on some interval containing a root \(r,\) and we take the starting approximation \(r \approx x_1\) and general approximation \(r \approx x_n,\) then Newton's Method enables us to approximate \(r\) using \begin{equation} x_{n + 1} = x_n - \frac{f(x_n)}{f'(x_n)} \pd \eqlabel{eq:newton-n} \end{equation} Newton's Method is said to converge to a root \(r\) if \(x_n \to r\) as \(n \to \infty\)—that is, if the approximations get closer and closer to the true value of \(r.\) In general, we can cease the iterative process if \(x_n\) and \(x_{n + 1}\) both agree to a desired number of decimal places. But Newton's Method fails if the approximations do not approach \(r;\) failure may occur in the following scenarios:

- If \(f'(x_n) = 0,\) then the tangent line does not cross the \(x\)-axis.

- If a function has multiple roots, then Newton's Method may converge to a different root.

- If \(f'(x_1)\) is close to \(0,\) then the tangent line poorly models the behavior of \(f,\) leading to an approximation that may be a worse estimate for \(r.\)

In any of these cases, try using a better choice of \(x_1.\)