3.5: Indeterminate Forms and L'Hopital's Rule

In Section 1.2 we used algebraic manipulation to evaluate limits in the indeterminate form \(\indZero.\) In this section we present a systematic method to evaluate limits in any indeterminate form—that is, \(\indZero,\) \(\indInfty,\) \(0 \times \infty,\) \(\infty - \infty,\) \(0^0,\) \(1^\infty,\) or \(\infty^0.\) We discuss the following topics:

- L'Hôpital's Rule

- Relative Rates of Growth and Decay

- Indeterminate Form \(0 \times \infty\)

- Indeterminate Form \(\infty - \infty\)

- Indeterminate Forms with Exponents: \(0^0,\) \(1^\infty,\) and \(\infty^0\)

L'Hôpital's Rule

Limits in the forms \(\indZero\) and \(\indInfty\) are examples of indeterminate forms, meaning we require further analysis to calculate the limit. For example, \[\lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x^2 - 9}{x - 3}\] is of the indeterminate form \(\indZero\) since both \((x^2 - 9)\) and \((x - 3)\) tend to \(0\) as \(x\) approaches \(3.\) But we factor the numerator to get \[ \lim_{x \to 3} \frac{(x + 3)(x - 3)}{(x - 3)} = \lim_{x \to 3} (x + 3) = 6 \pd \] Algebraic manipulation allows us to evaluate this limit, but for other limits we don't have this resource. L'Hôpital's Rule, given below, provides us a remedy to evaluate such limits.

In words, we differentiate the numerator and denominator of the fraction whose limit is of an indeterminate form \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty,\) and reevaluate the limit. The notations \(\indZero\) and \(\indInfty\) are forms to model a quotient of limits, each of which tends to \(0\) or \(\infty.\) These expressions are meaningless on their own, so it's incorrect to state that a limit equals \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty.\) L'Hôpital's Rule also applies to one-sided limits and limits at infinity. The proof of L'Hôpital's Rule is presented in Appendix A.2.

As an example, consider \(\lim_{x \to 0} (\sin x/x).\) Using L'Hôpital's Rule, we differentiate the numerator and denominator to get \[ \ba \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\deriv{}{x} (\sin x)}{\deriv{}{x} (x)} &= \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\cos x}{1} = 1 \cma \ea \] which confirms the value obtained from Chapter 1.

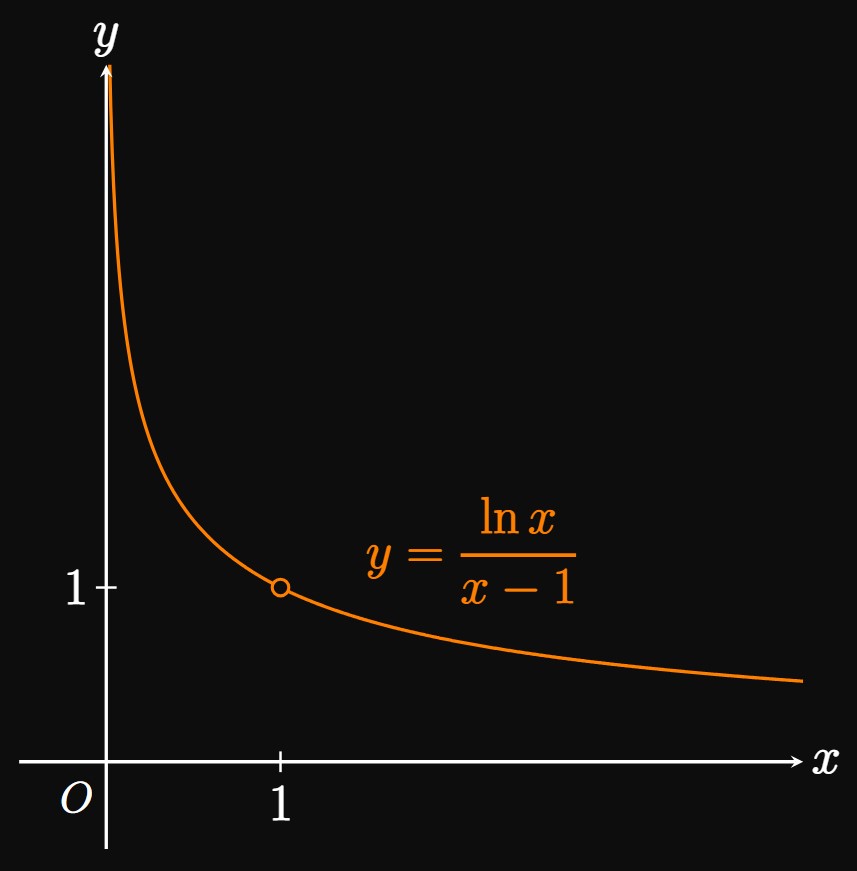

The functions \(\ln x\) and \((x - 1)\) both tend to \(0\) as \(x\) approaches \(1.\) Therefore, the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indZero.\) Since these functions are differentiable, we apply L'Hôpital's Rule: \[ \ba \lim_{x \to 1}\frac{\ln x}{x - 1} &= \lim_{x \to 1} \frac{\deriv{}{x} (\ln x)}{\deriv{}{x} (x - 1)} \nl &= \lim_{x \to 1} \frac{1/x}{1} \nl &= \frac{1/1}{1} \nl &= \boxed{1} \ea \] As shown in Figure 1, the graph of \(y = (\ln x)/(x - 1)\) has a removable discontinuity at \((1, 1).\)

You may need to use L'Hôpital's Rule multiple times before obtaining a definitive answer, as the resulting limit may still be in the indeterminate form \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty.\) The following example shows one of these scenarios.

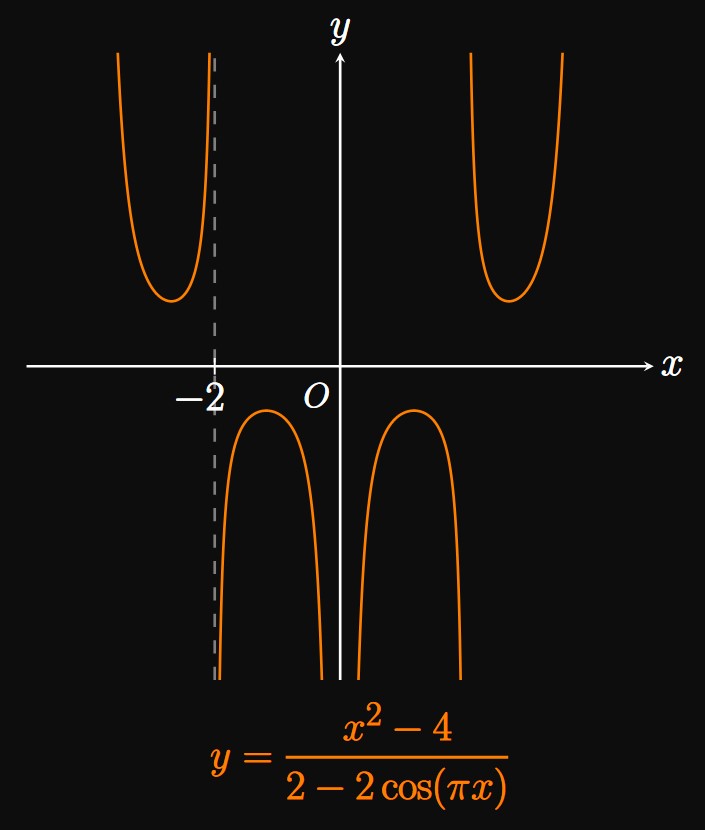

The numerator and denominator both approach \(0\) as \(x\) approaches \(-2,\) so the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indZero.\) Both functions are differentiable, so we apply L'Hôpital's Rule: \[ \ba \lim_{x \to -2} \frac{x^2 - 4}{2 - 2 \cos(\pi x)} &= \lim_{x \to -2} \frac{\deriv{}{x}(x^2 - 4)}{\deriv{}{x}[2 - 2 \cos (\pi x)]} \nl &= \lim_{x \to -2} \frac{2x}{2 \pi \sin (\pi x)} \pd \nl \ea \] At \(x = -2,\) the denominator is \(0\) and the numerator is nonzero. Thus, the graph of \(y = 2x/[2 \pi \sin(\pi x)]\) has a vertical asymptote at \(x = -2.\) The limit therefore does not exist. (See Figure 2.)

Relative Rates of Growth and Decay

One application of L'Hôpital's Rule involves the relative rates of growth or decay of various functions. Consider two positive functions: \(f\) and \(g.\) To determine which function grows faster, we consider the limit \[L = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \pd \] This quotient initiates a battle between \(f\) and \(g \col\) If \(f\) grows faster than \(g,\) then \(L\) approaches infinity. But if \(g\) grows faster than \(f,\) then \(L\) approaches \(0.\) Lastly, if \(f\) and \(g\) grow at the same rate, then \(L\) equals a nonzero constant.

- If \(L = \infty,\) then \(f\) grows faster than \(g.\)

- If \(L = 0,\) then \(g\) grows faster than \(f.\)

- If \(L\) is a nonzero value, then \(f\) and \(g\) grow at the same rate.

We consider some ratio of \(f\) and \(g\) as \(x \to \infty\)—for example, \[L = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x^{1/5}}{\ln x} \cma \] which is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) Therefore, we apply L'Hôpital's Rule to get \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\frac{1}{5} x^{-4/5}}{1/x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{5}x^{1/5} \nl &= \infty \pd \ea \] Because \(L = \infty,\) \(f(x) = x^{1/5}\) grows faster than \(g(x) = \ln x.\) As \(x\) approaches infinity, \(f(x)\) tries to force \(f(x)/g(x)\) to infinity, while \(g(x)\) tries to make the quotient decay to \(0.\) Because the quotient \(f(x)/g(x)\) approaches infinity, \(f(x) = x^{1/5}\) overpowers \(g(x) = \ln x\) and therefore grows faster.

REMARK This analysis shows that \(f(x) = x^{1/5}\) eventually grows faster than \(g(x) = \ln x.\) It turns out that \(x^{1/5}\) surpasses \(\ln x\) when \(x \approx 332\cmaNum105.108.\) An untrained observer may plot these functions and incorrectly conclude that \(g(x) = \ln x\) grows faster as \(x \to \infty.\)

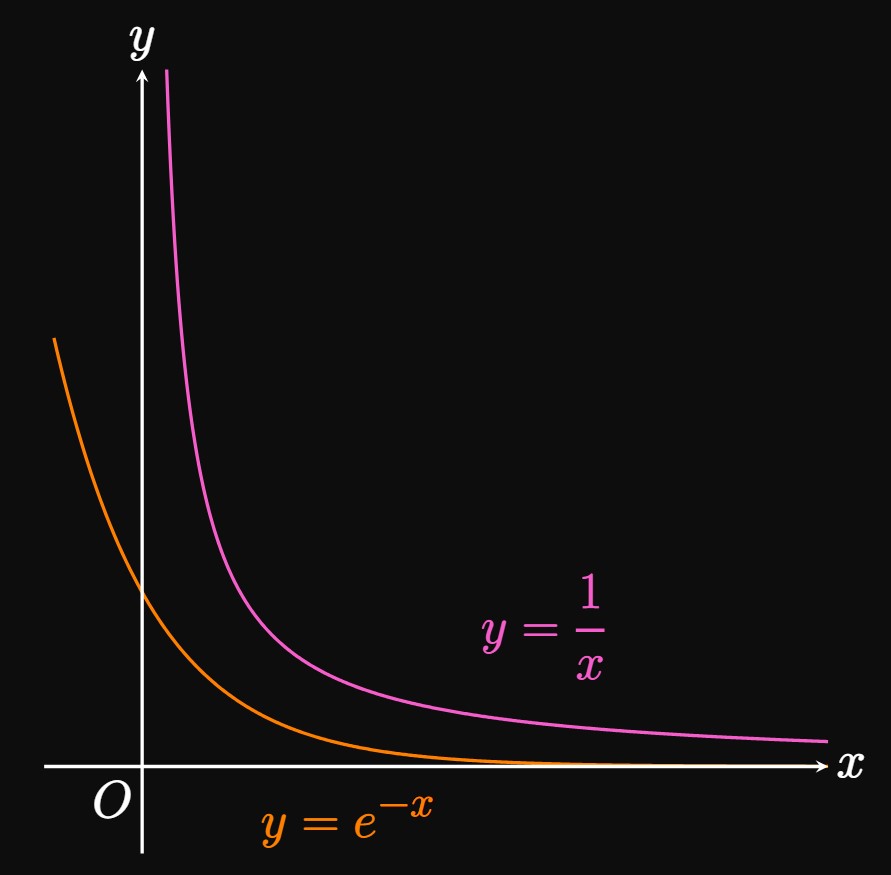

We consider some ratio of \(f\) and \(g\)—say, \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{e^{-x}}{1/x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x}{e^x} \cma \ea \] which is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) Then applying L'Hôpital's Rule gives \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\deriv{}{x}(x)}{\deriv{}{x} \par{e^x}} &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{e^x} = 0 \pd \ea \] Since \(L = 0,\) we conclude that \(f(x) = e^{-x}\) decays faster than \(g(x) = 1/x.\) (See Figure 3.)

Indeterminate Form \(0 \times \infty\)

There are several other types of indeterminate limits.

One such example is \(0 \times \infty,\)

which arises when one function approaches \(0\) and the other approaches \(\infty,\)

leading to a tug-of-war.

Generally, we resolve these limits by rewriting the product as a quotient

and applying L'Hôpital's Rule.

The following box describes this procedure.

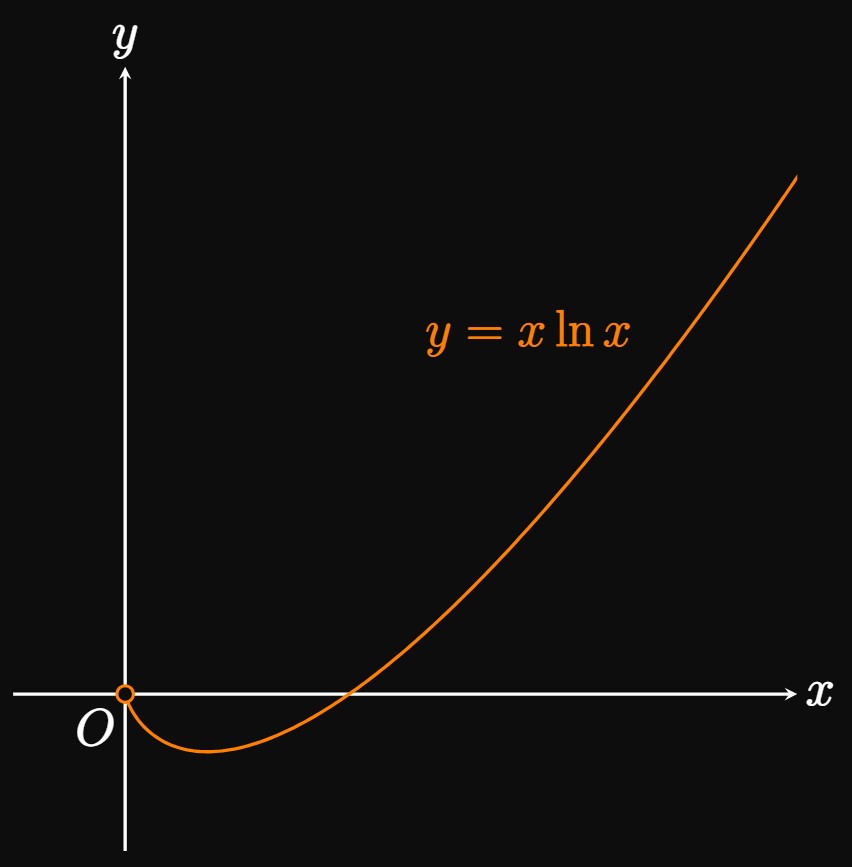

As \(x \to 0^+,\) \(x \to 0\) and \(\ln x \to -\infty.\) Thus, the limit \[L = \lim_{x \to 0^+} (x \ln x)\] is in the indeterminate form \(0 \times \infty.\) A battle exists between \(x\) and \(\ln x \col\) As \(x \to 0^+,\) the term \(x\) tries to force the product \(x \ln x\) to \(0,\) while \(\ln x\) tries to push the product to negative infinity. To analyze the limit, we rewrite the product \(x \ln x\) as some quotient—for example, \[L = \lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{\ln x}{1/x} \cma \] which is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) By L'Hôpital's Rule, \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{\deriv{}{x} (\ln x)}{\deriv{}{x} (1/x)} \nl &= \lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{1/x}{-1/x^2} \nl &= \lim_{x \to 0^+} (-x) \nl &= \boxed{0} \ea \] Thus, as \(x \to 0^+,\) the term \(x\) overpowers \(\ln x\) and forces the product \(x \ln x\) to \(0.\) The graph of \(y = x \ln x\) is shown in Figure 4.

REMARK If we choose to rewrite the limit as \[L = \lim_{x \to 0^+} \frac{x}{1/(\ln x)} \cma\] then the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indZero.\) Applying L'Hôpital's Rule would yield the same result, \(L = 0,\) through a slightly more cumbersome differentiation process.

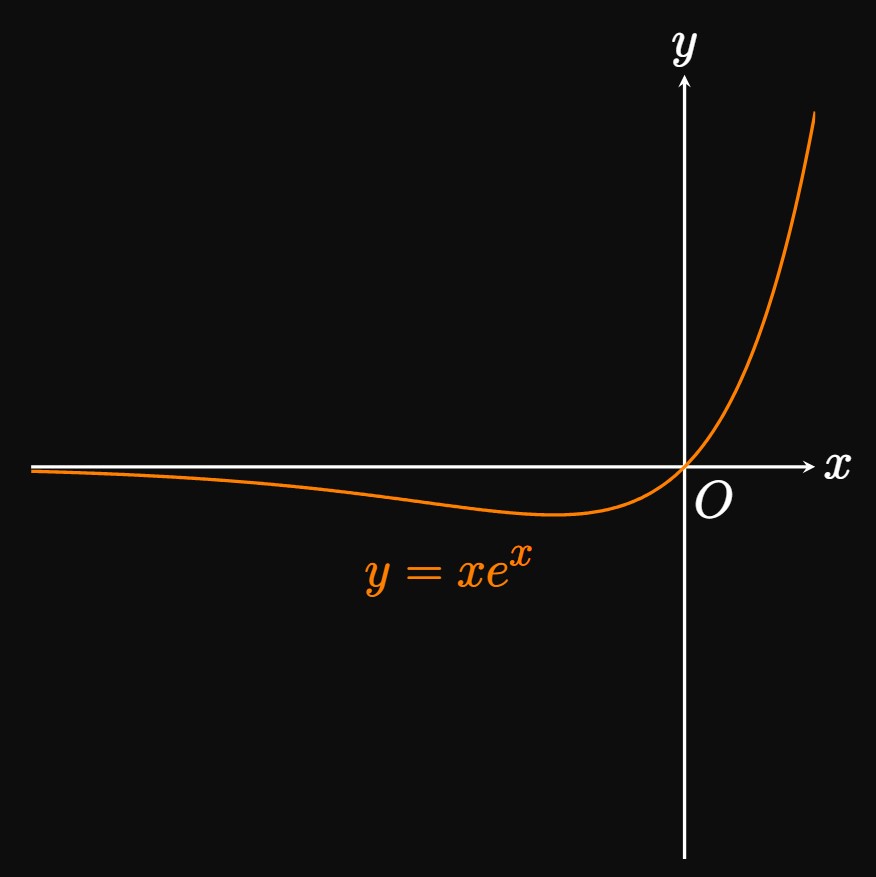

The limit is in the indeterminate form \(0 \times \infty,\) so we rewrite the expression as a quotient: \[ \lim_{x \to -\infty} xe^{x} = \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{x}{1/e^x} \cma \] which is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) Then by L'Hôpital's Rule, the limit is \[ \ba \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{\deriv{}{x}(x)}{\deriv{}{x} (1/e^x)} &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{1}{-1/e^x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} -e^x \nl &= \boxed{0} \ea \] The graph of \(y = x e^x\) is shown in Figure 5.

A Bad Quotient If we choose the quotient \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{e^x}{1/x},\] which is in the indeterminate form \(\indZero,\) then L'Hôpital's Rule gives \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{e^x}{-1/x^2} \pd \] Further applications of L'Hôpital's Rule then give \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{e^x}{2/x^3} \cma \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{e^x}{-6/x^4} \cma \dots \cma\] leading nowhere because repeated iterations are still in the indeterminate form \(\indZero.\) In this problem only one choice, writing the quotient in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty,\) provides an answer.

Indeterminate Form \(\infty - \infty\)

If two functions \(p\) and \(q\) satisfy \[\lim_{x \to a} p(x) = \infty \and \lim_{x \to a} q(x) = \infty \cma \] then \(L = \lim_{x \to a} [p(x) - q(x)]\) is in the indeterminate form \(\infty - \infty.\) Because \(p\) and \(q\) may have different growth rates, it is unclear what occurs to their difference, \(p(x) - q(x),\) as \(x \to a.\) The following box describes the method for resolving these limits.

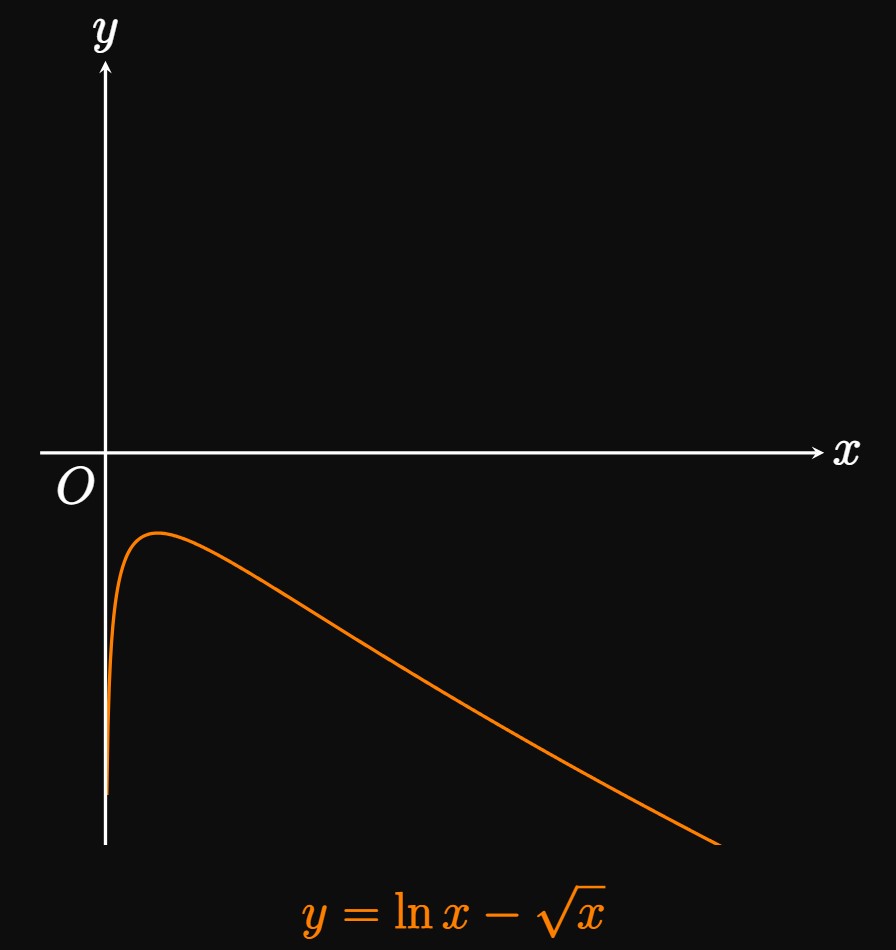

As \(x\) approaches infinity, both \(\ln x\) and \(\sqrt x\) approach infinity. Thus, the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\infty - \infty.\) Our goal is to manipulate the difference to be a product: Factoring out \(\sqrt x\) shows \[\lim_{x \to \infty} \par{\ln x - \sqrt x \,} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \sqrt x \left(\frac{\ln x}{\sqrt x} - 1 \right) \pd\] L'Hôpital's Rule gives \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ln x}{\sqrt x} &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1/x}{\dfrac{1 \strut}{2 \sqrt x}} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2 \sqrt x}{x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{2}{\sqrt x} \nl &= 0 \pd \ea \] Thus, as \(x \to \infty,\) \[\left(\frac{\ln x}{\sqrt x} - 1 \right) \to -1 \pd\] Because \(\sqrt x \to \infty\) as \(x \to \infty,\) we must have \[\lim_{x \to \infty} \sqrt x \left(\frac{\ln x}{\sqrt x} - 1 \right) = \boxed{-\infty}\] The graph of \(y = \ln x - \sqrt x\) is shown in Figure 6.

REMARK If we choose to factor out \(\ln x,\) then the limit becomes \[\lim_{x \to \infty} \ln x \left(1 - \frac{\sqrt x}{\ln x} \right) \pd\] As \(x \to \infty,\) L'Hôpital's Rule shows \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\sqrt x}{\ln x} &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\dfrac{1 \strut}{2 \sqrt x}}{1/x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x}{2 \sqrt x} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\sqrt x}{2} \nl &= \infty \pd \ea \] As \(x \to \infty,\) \[\ln x \to \infty \and \par{1 - \frac{\sqrt x}{\ln x}} \to - \infty \pd \] The product of \(\infty\) and \(-\infty\) is \(-\infty,\) so this approach yields the same answer.

Indeterminate Forms with Exponents: \(0^0,\) \(1^\infty,\) and \(\infty^0\)

Indeterminate forms with exponents are \[\andThree{0^0}{1^\infty}{\infty^0} \pd\] Unlike the indeterminate forms \(0 \times \infty\) and \(\infty - \infty,\) we cannot manipulate expressions into the indeterminate forms \(\indZero\) and \(\indInfty\) by factorization. Instead, the strategy revolves around logarithms, as described by the following steps.

- Let \(y = [p(x)]^{q(x)}.\) It then follows that \[\ln y = q(x) \ln[p(x)] \pd \]

- Evaluate the limit \[L = \lim_{x \to a} \ln y \pd \] You may need to manipulate \(L\) into the indeterminate form \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty\) and use L'Hôpital's Rule.

- Conclude that \[\lim_{x \to a} y = e^L \pd\]

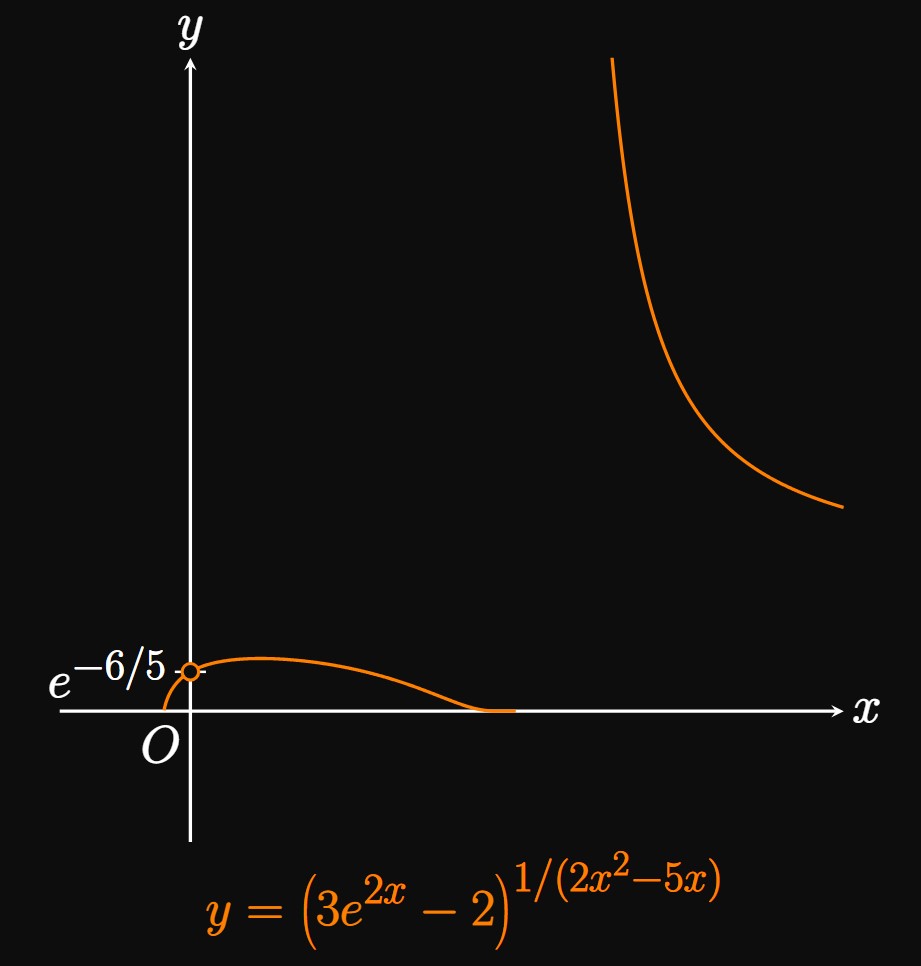

As \(x \to 0^-,\) \[\par{3e^{2x} - 2} \to 1 \and \frac{1}{2x^2 - 5x} \to \infty \pd\] This limit is therefore in the indeterminate form \(1^\infty.\) We first let \[y = \par{3e^{2x} - 2}^{1/({2x^2 - 5x})} \pd \] Taking the natural logarithm of both sides, we get \[ \ba \ln y &= \ln \left[ \left( 3e^{2x} - 2 \right)^{1/({2x^2 - 5x})} \right] \nl &= \frac{1}{2x^2 - 5x} \ln \left( 3e^{2x} - 2 \right) \pd \ea \] Now \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to 0^-} \ln y \nl &= \lim_{x \to 0^-} \frac{1}{2x^2 - 5x} \ln \left( 3e^{2x} - 2 \right) \nl &= \lim_{x \to 0^-} \frac{\ln \left( 3e^{2x} - 2 \right)}{2x^2 - 5x} \pd \ea \] This limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indZero,\) so L'Hôpital's Rule gives \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to 0^-} \frac{\dfrac{6e^{2x}}{3e^{2x} - 2 \strut}}{4x - 5} \nlLong &= \frac{\dfrac{6 e^0}{3e^0 - 2 \strut}}{4(0) - 5} \nlLong &= -\frac{6}{5} \pd \ea \] Because \(L = -6/5,\) \[\lim_{x \to 0^-} \par{3e^{2x} - 2}^{1/({2x^2 - 5x})} = e^L = \boxed{e^{-6/5}}\] (See Figure 7.)

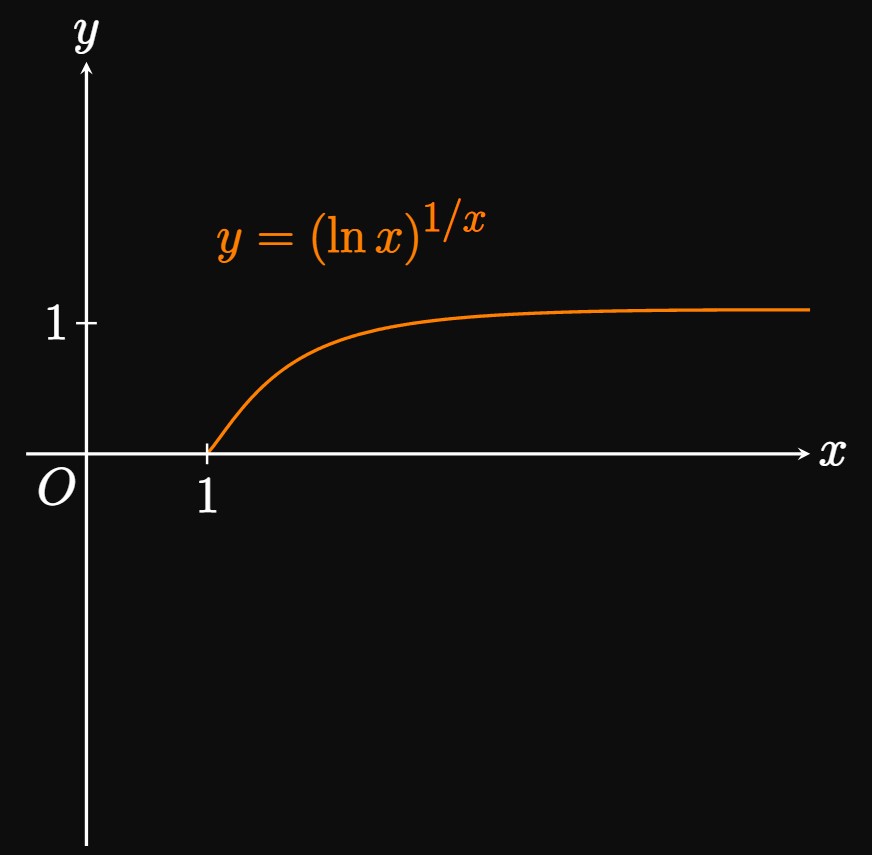

As \(x \to \infty,\) \[\ln x \to \infty \and \frac{1}{x} \to 0 \cma\] so the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\infty^0.\) We first let \[y = \left(\ln x \right)^{1/x} \pd \] Taking the natural logarithm of both sides produces \[\ln y = \frac{1}{x} \ln \left(\ln x \right) \pd\] Then \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \ln y \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x} \ln \left(\ln x \right) \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ln(\ln x)}{x} \pd \ea \] This limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty,\) so applying L'Hôpital's Rule gives \[ \ba L &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\dfrac{1}{x\ln x \strut}}{1} \nl &= 0 \pd \ea \] Since \(L = 0,\) we have \[\lim_{x \to \infty} (\ln x)^{1/x} = e^L = e^0 = \boxed{1} \] As shown in Figure 8, the graph of \(y = (\ln x)^{1/x}\) has a horizontal asymptote of \(y = 1.\)

L'Hôpital's Rule

Let \(f\) and \(g\) be differentiable and \(g'(x) \ne 0\) on some neighborhood around \(a\) (except possibly at

Relative Rates of Growth and Decay Let \(f\) and \(g\) be differentiable, nonzero functions. To assess whether \(f\) or \(g\) grows faster as \(x \to \infty,\) take a ratio of the two functions, \[L = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \pd \] The following conclusions arise:

- If \(L = \infty,\) then \(f\) grows faster than \(g.\)

- If \(L = 0,\) then \(g\) grows faster than \(f.\)

- If \(L\) is a nonzero value, then \(f\) and \(g\) grow at the same rate.

Indeterminate Form \(0 \times \infty\) Let \(p\) and \(q\) be differentiable, nonzero functions. If \[L = \lim_{x \to a}[p(x) q(x)]\] is in the indeterminate form \(0 \times \infty,\) then force \(L\) into the indeterminate form \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty\) by rewriting it as \[ \lim_{x \to a} \frac{p(x)}{1/q(x)} \or \lim_{x \to a} \frac{q(x)}{1/p(x)} \pd \] Decide which form is easier to evaluate using L'Hôpital's Rule. (In some instances only one form leads to an answer.)

Indeterminate Form \(\infty - \infty\) If \(p\) and \(q\) are differentiable, nonzero functions such that \[ L = \lim_{x \to a} [p(x) - q(x)] \] is in the indeterminate form \(\infty - \infty,\) then rewrite \(L\) as the limit of a product by factoring, rationalizing, or combining fractions. Then apply L'Hôpital's Rule if needed.

Indeterminate Forms with Exponents: \(0^0,\) \(1^\infty,\) and \(\infty^0\) Suppose \[\lim_{x \to a} [p(x)]^{q(x)}\] is in the indeterminate form \(0^0, 1^{\infty},\) or \(\infty^0.\)

- Let \(y = [p(x)]^{q(x)}.\) It then follows that \[\ln y = q(x) \ln[p(x)] \pd \]

- Evaluate the limit \[L = \lim_{x \to a} \ln y \pd \] You may need to manipulate \(L\) into the indeterminate form \(\indZero\) or \(\indInfty\) and use L'Hôpital's Rule.

- Conclude that \[\lim_{x \to a} y = e^L \pd\]