3.3: Using the First and Second Derivatives

When we analyze graphs, it is imperative that we be able to describe their properties. From algebra class, we categorized a graph either as increasing or decreasing over an interval. But calculus provides us one more property—concavity, which describes the change in a function's rate of change. Moreover, how do we test whether a function has a relative minimum or maximum? A function's first and second derivatives play vital roles in answering these questions. In this section we discuss the following topics:

Increasing and Decreasing

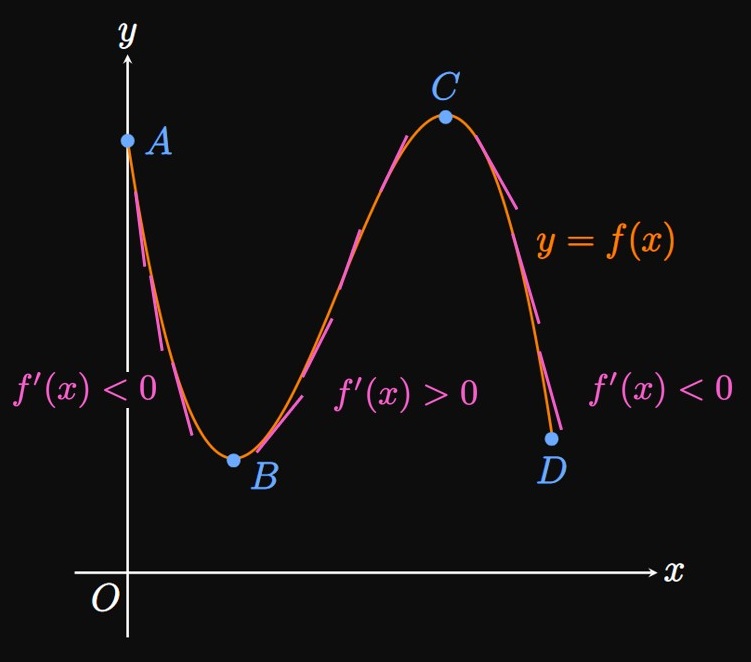

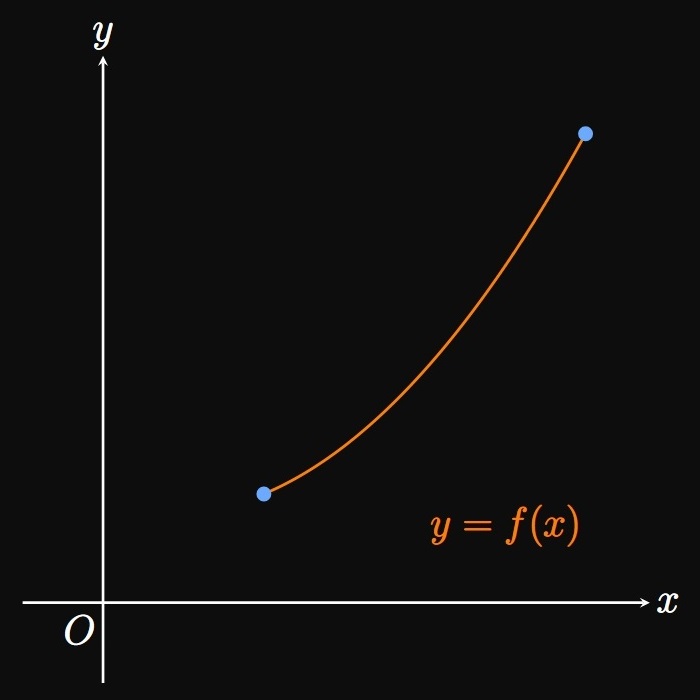

Let \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) be two numbers such that \(x_1 \lt x_2.\) If a function \(f\) is increasing over an interval, then \(f(x_1) \lt f(x_2)\) for \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) in that interval. Conversely, \(f\) is decreasing if \(f(x_1) \gt f(x_2).\) In Figure 1, the graph of \(y = f(x)\) is decreasing between points \(A\) and \(B,\) increasing between \(B\) and \(C,\) and decreasing between \(C\) and \(D.\) When \(f\) is increasing, we see that tangents to the curve have positive slope; thus, \(f' \gt 0.\) But when \(f\) is decreasing, the tangents have negative slope and so \(f' \lt 0.\) We therefore conclude the following: \(f\) is increasing if \(f' \gt 0\) and \(f\) is decreasing if \(f' \lt 0.\)

- If \(f' \gt 0\) on an interval, then \(f\) is increasing on that interval.

- If \(f' \lt 0\) on an interval, then \(f\) is decreasing on that interval.

PROOF Consider the interval \([x_1, x_2]\) with \(x_1 \lt x_2.\) We must prove that if \(f'(x) \gt 0\) in this interval, then \(f(x_1) \lt f(x_2)\) and so \(f\) is increasing. Then we aim to show that if \(f'(x) \lt 0\) in this interval, then \(f(x_1) \gt f(x_2),\) indicating that \(f\) is decreasing. We assume that \(f\) is continuous over \([x_1, x_2]\) and differentiable over \((x_1, x_2).\) Thus, the Mean Value Theorem (Section 3.2) guarantees a number \(c\) in \((x_1, x_2)\) such that \begin{equation} f(x_2) - f(x_1) = f'(c) (x_2 - x_1) \pd \label{eq:proof-f'-mvt} \end{equation} If \(f' \gt 0\) over \((x_1, x_2),\) then the right-hand side of \(\eqref{eq:proof-f'-mvt}\) becomes a product of positive numbers because \(f'(c) \gt 0\) and \(x_2 - x_1 \gt 0.\) Consequently, \[f(x_2) - f(x_1) \gt 0 \or f(x_1) \lt f(x_2) \cma\] so \(f\) is increasing on \([x_1, x_2].\) Hence, part (a) is proved. If \(f' \lt 0\) over \((x_1, x_2),\) then in \(\eqref{eq:proof-f'-mvt}\) \(f'(c) \lt 0,\) so the right-hand side is a negative quantity. Thus, \[f(x_2) - f(x_1) \lt 0 \or f(x_1) \gt f(x_2) \cma\] meaning \(f\) is decreasing over \([x_1, x_2].\) Part (b) is therefore proved. \[\qedproof\]

First-Derivative Test

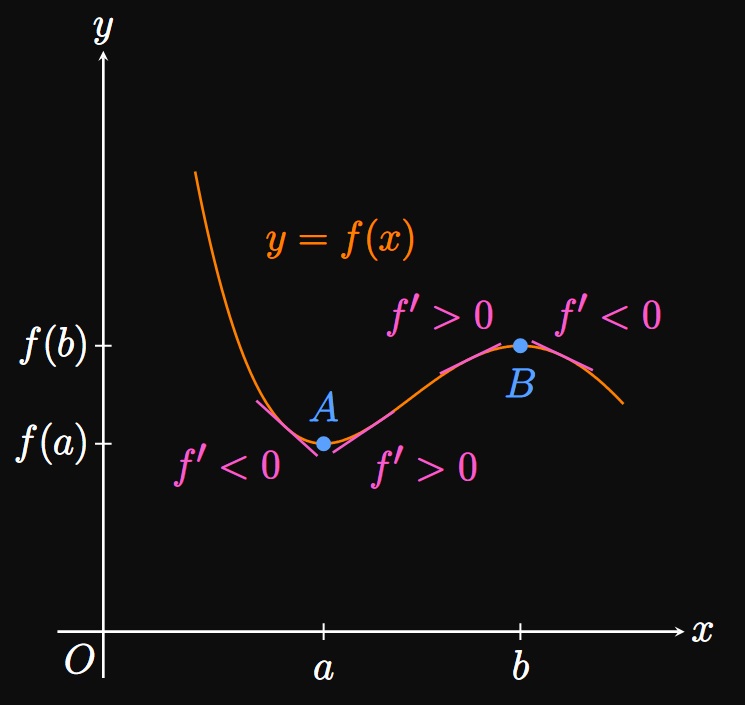

In Section 3.1 we learned to find a function's relative extrema by analyzing its critical numbers. Yet how do we test whether the function has a relative minimum or relative maximum at the critical number? In Figure 4 the function \(f\) has a relative minimum at \((a, f(a))\) and a relative maximum at \((b, f(b)).\) Observe that \(f\) is decreasing to the left of \(a\) and increasing to the right of \(a.\) Through our discussion of Increasing and Decreasing, \(f'\) therefore flips sign from negative to positive at \(a.\) Conversely, \(f\) is increasing to the left of \(b\) and decreasing to the right of \(b.\) Consequently, \(f'\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(b.\) These observations describe the First-Derivative Test, defined below.

- \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has no relative extremum at \(c\) if \(f'\) does not change sign at \(c.\)

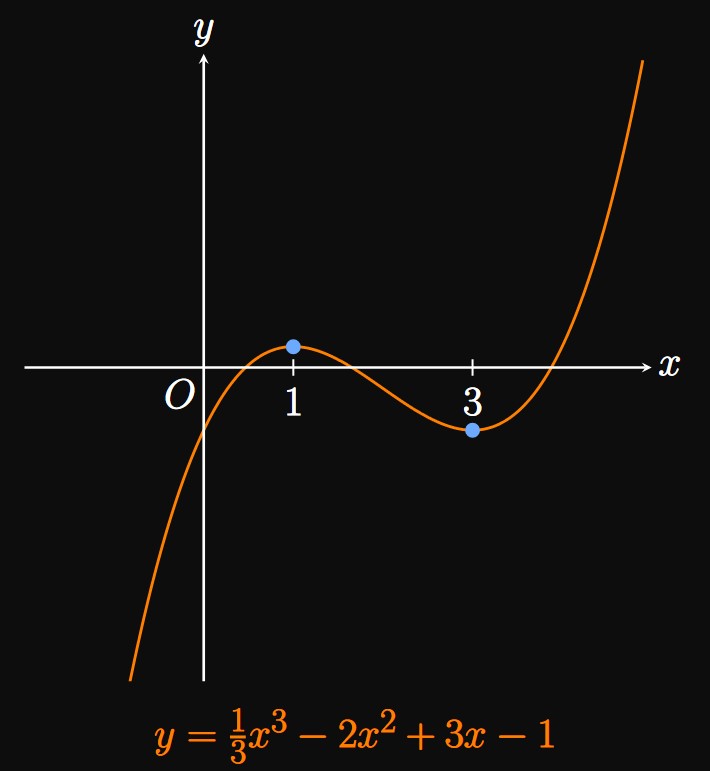

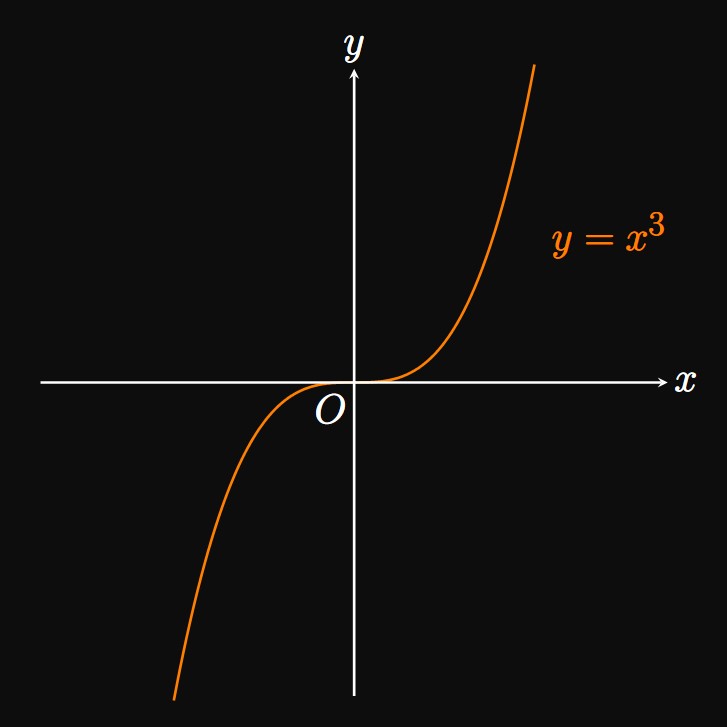

The First-Derivative Test can also prove the nonexistence of a relative extremum. For example, the derivative of \(g(x) = x^3\) is \(g'(x) = 3x^2.\) Note that \(g'(0) = 0,\) but \(g'\) does not change sign at \(0\) because \(g'(x) = 3x^2\) is strictly nonnegative. Accordingly, the First-Derivative Test asserts that \(g(x) = x^3\) does not have a relative extremum at \(x = 0.\) (See Figure 5.)

| Interval of \(x\) | \(g'(x) = 6x(x - 1)\) |

| \((-\infty, 0)\) | \(+\) |

| \((0, 1)\) | \(-\) |

| \((1, \infty)\) | \(+\) |

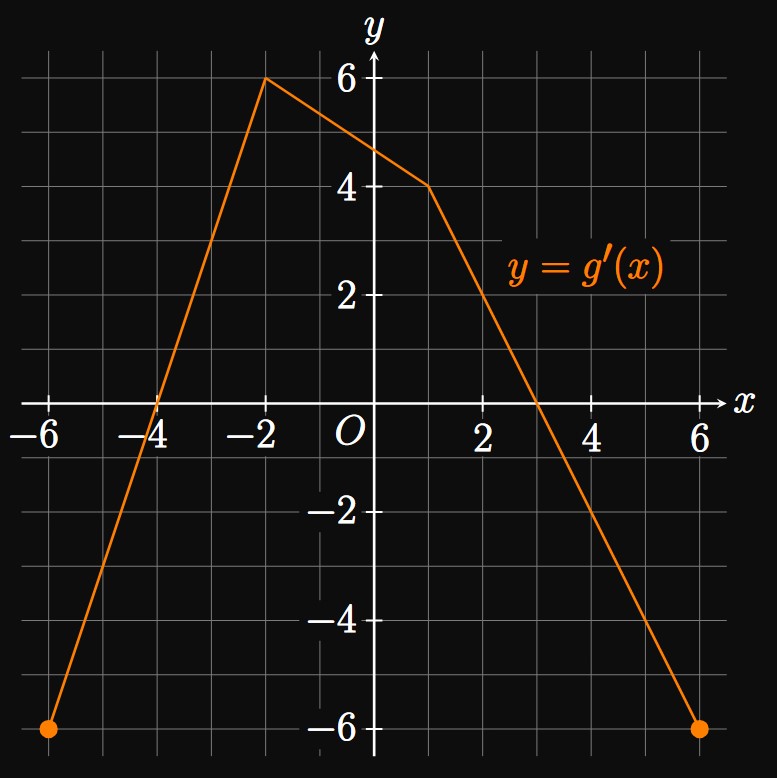

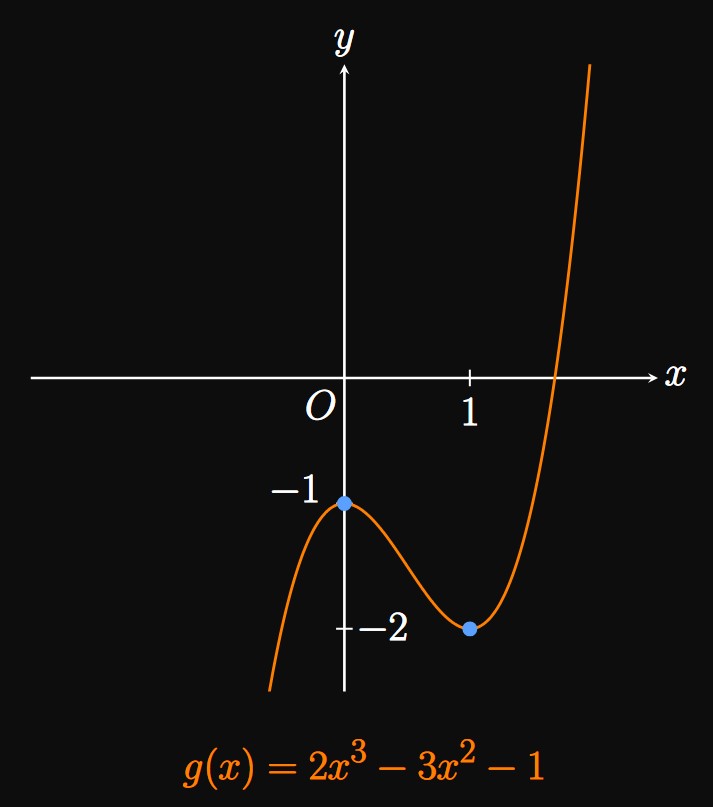

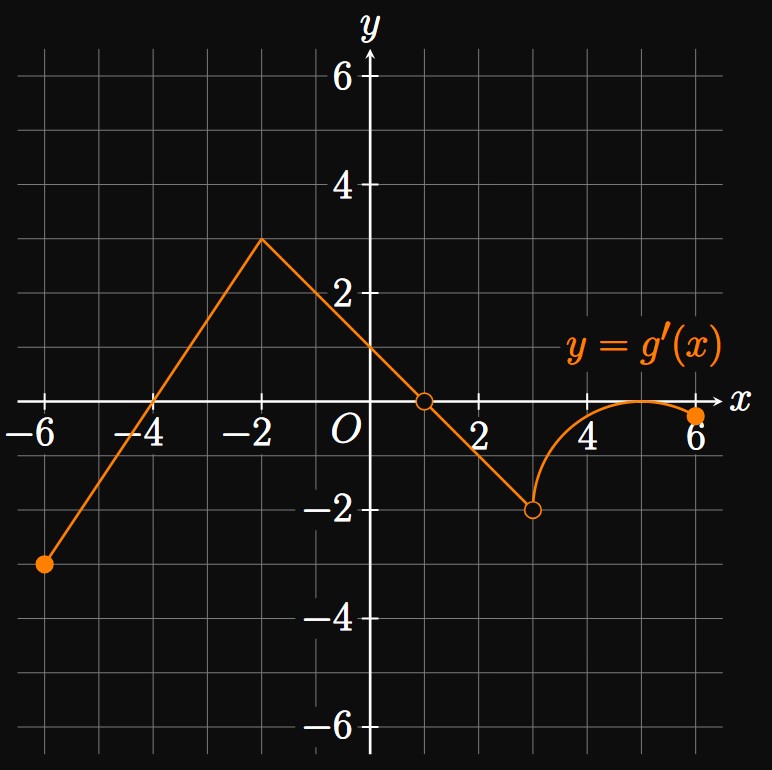

A number \(c\) is a critical number of \(g\) if it's in the domain of \(g\) and if \(g'(c) = 0\) or \(g'(c)\) is undefined. From Figure 7, \(g'(x) = 0\) when \(x = -4\) and \(x = 5.\) Also, \(g'(x)\) is undefined at \(x = 1\) and \(x = 3,\) but both numbers are in the domain of \(g\) because \(g\) is given to be continuous on \([-6, 6].\) Therefore, the critical numbers of \(g\) are \(-4,\) \(1,\) \(3,\) and \(5.\) The following table shows the sign of \(g'\) for intervals bounded by these values.

| Interval of \(x\) | \(g'(x)\) |

| \([-6, -4)\) | \(-\) |

| \((-4, 1)\) | \(+\) |

| \((1, 3)\) | \(-\) |

| \((3, 5)\) | \(-\) |

| \((5, 6]\) | \(-\) |

- a relative minimum at \(x = -4\) because the sign of \(g'\) flips from negative to positive at \(x = -4.\)

- a relative maximum at \(x = 1\) because the sign of \(g'\) flips from positive to negative at \(x = 1.\)

- no extrema at \(x = 3\) or \(x = 5\) because \(g'\) does not change sign at those points.

Concavity

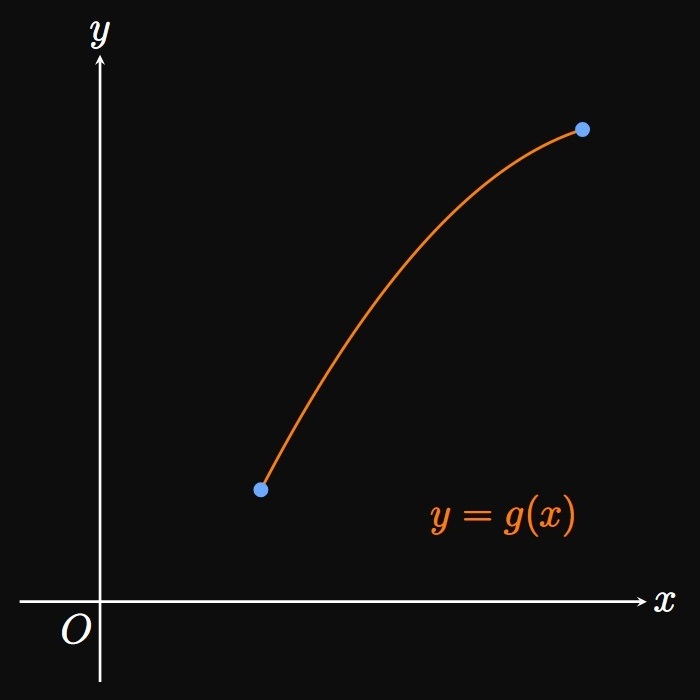

We can determine whether a function is increasing or decreasing over an interval.

But we delve one step deeper to consider concavity.

In Figure 8A and Figure 8B,

both functions \(f\) and \(g\) are increasing,

but they are bent differently:

We call \(f\) concave upward

(or simply concave up)

and \(g\) concave downward

(or concave down).

The word concave means curving inward;

it's easy to remember the phrase cave in.

The graph of \(f\) appears to bend inward when viewed from above,

whereas the graph of \(g\) looks to arch inward if we view it from below.

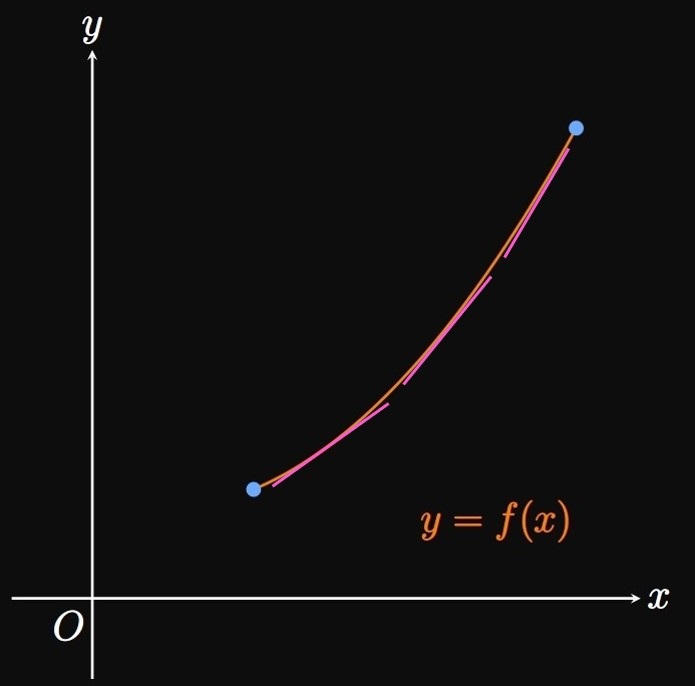

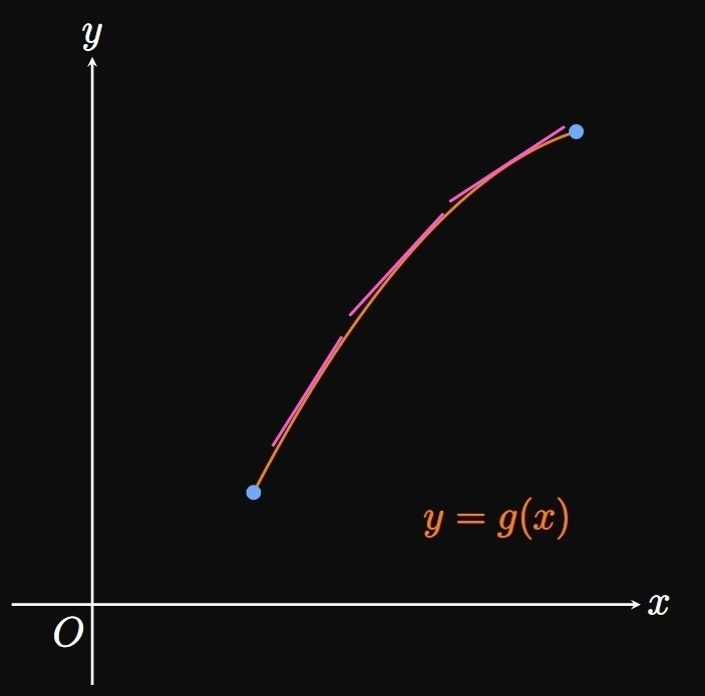

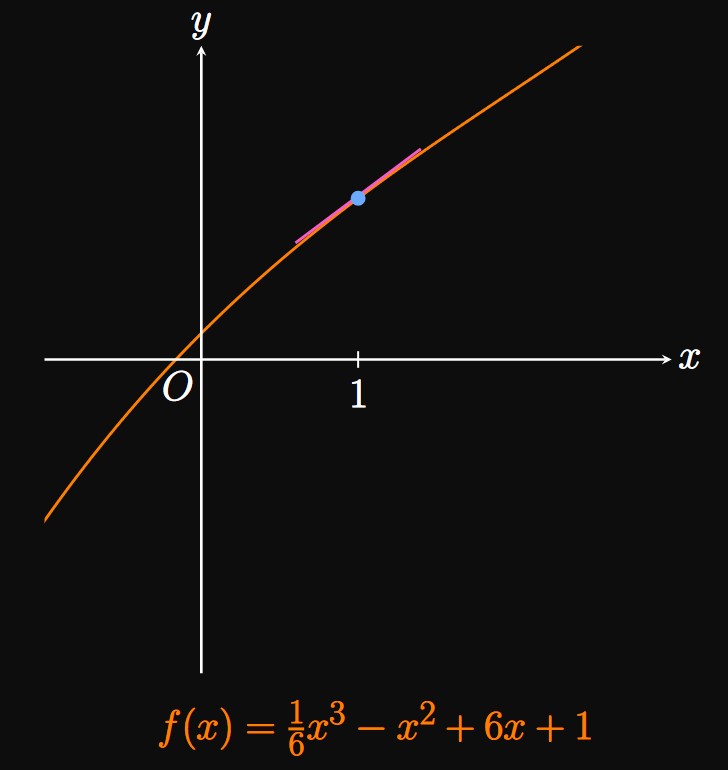

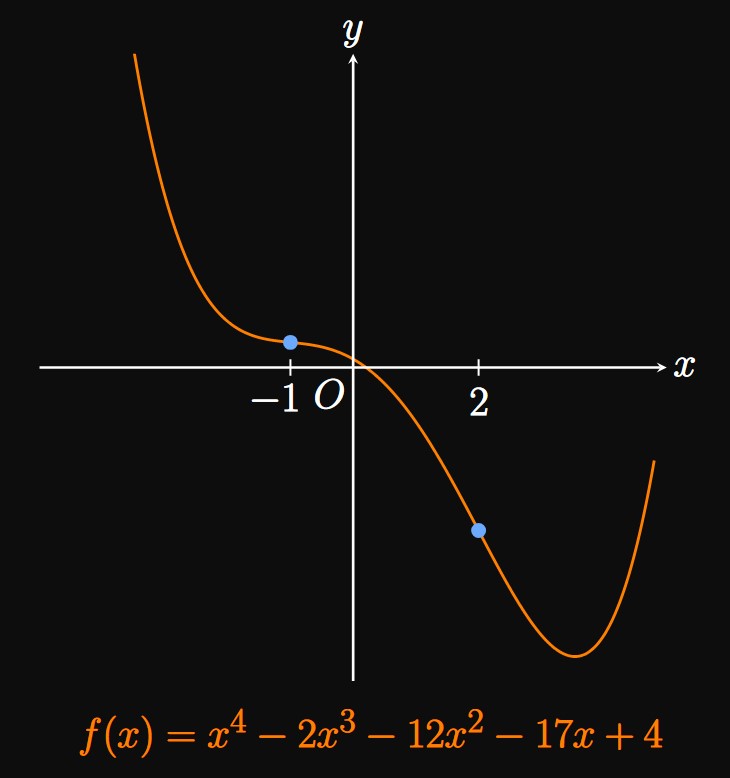

If we draw tangents to the graph of \(f,\) whose graph is concave up, then we see that the graph lies above all the tangents (Figure 9A). Thus, the rate of change of \(f\) is increasing. In other words, the derivative \(f'\) is an increasing function; accordingly, the second derivative \(f''\) is positive. By contrast, drawing tangents to the graph of \(g\) (whose graph is concave down) shows that the graph lies below all the tangents (Figure 9B). Because the slopes of the tangents are decreasing, \(g'\) is a decreasing function and so \(g''\) is negative.

- If \(f''(x) \gt 0\) for all \(x\) in an interval, then the graph of \(f\) is concave up on that interval.

- If \(f''(x) \lt 0\) for all \(x\) in an interval, then the graph of \(f\) is concave down on that interval.

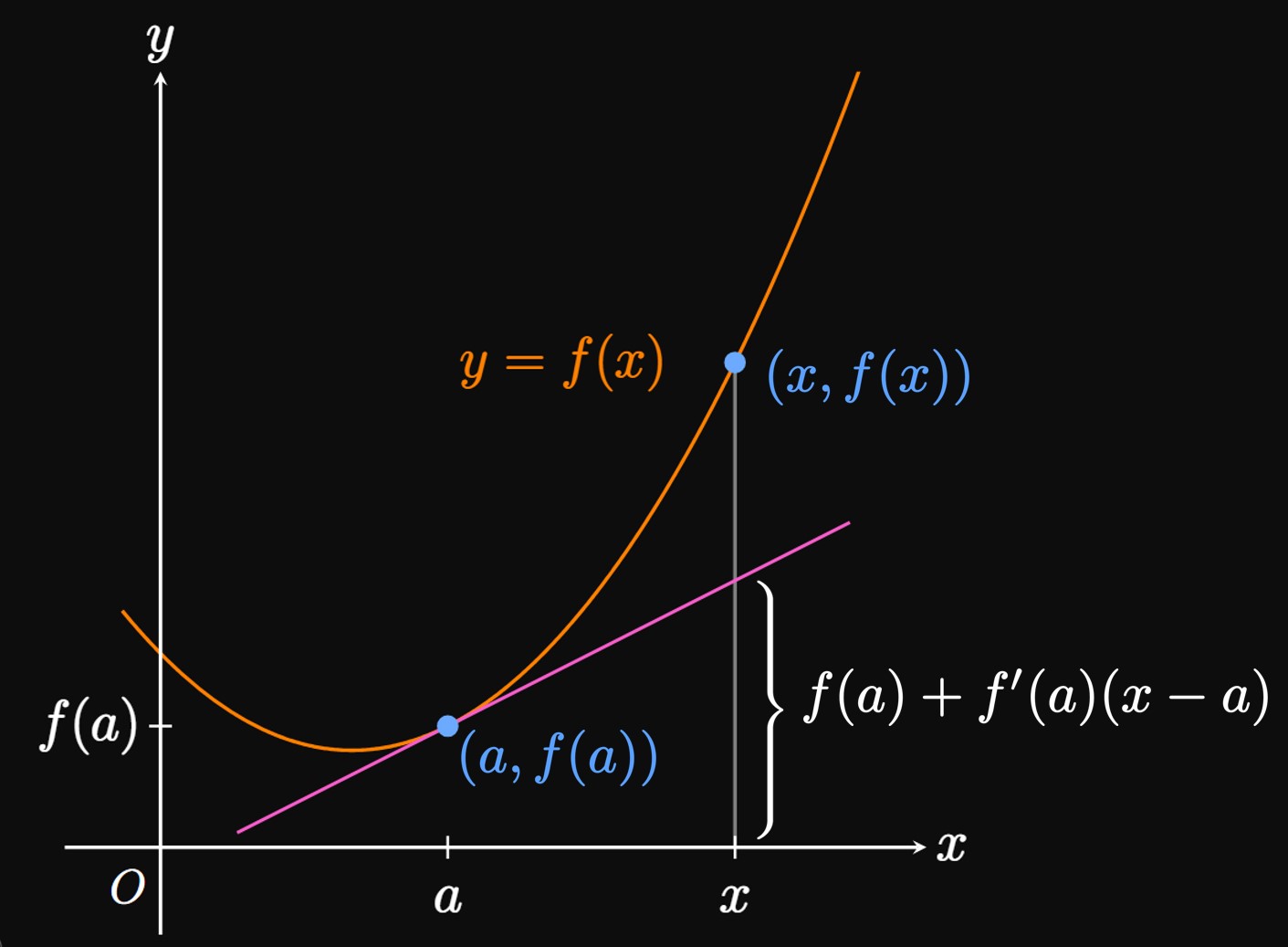

PROOF

To prove part (a) of the Concavity Test,

we begin by letting \(a\) be any number on an interval \(I.\)

An equation of the tangent line to \(y = f(x)\) at \((a, f(a))\) is

\[y - f(a) = f'(a) (x - a) \pd\]

(See Figure 10.)

At some \(x \gt a,\) the \(y\)-value of the tangent line is \(f(a) + f'(a) (x - a),\)

so the goal is to show that the curve is above the tangent line—that is,

\[f(x) \gt f(a) + f'(a) (x - a) \pd\]

By the Mean Value Theorem, there is a number \(c\) in \((a, x)\) such that

\begin{align}

f'(c) &= \frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x - a} \nonum \nl

\implies f(x) &= f(a) + f'(c) (x - a) \pd \label{eq:mvt-I}

\end{align}

Since \(f'' \gt 0\) on \(I,\) it follows that \(f'\) is increasing on \(I.\)

Accordingly, \(f'(c) \gt f'(a)\) (since

A point at which the graph of \(f\) changes concavity—from concave up to concave down or from concave down to concave up—is called an inflection point. For example, in Example 6 the graph of \(f\) switches from concave down to concave up at \(x = 2.\) Thus, \(x = 2\) is the location of an inflection point of \(f.\) An easy way to estimate the location of an inflection point of \(f\) is to identify a point at which \(f\) crosses its tangent.

Second-Derivative Test

Another application of second derivatives is the Second-Derivative Test, shown below. This test is an alternative to the First-Derivative Test.

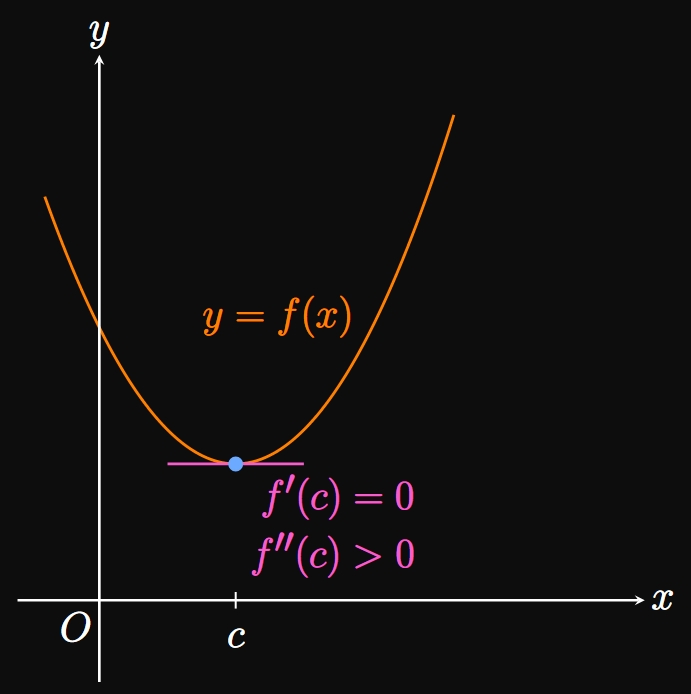

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \gt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(x = c.\)

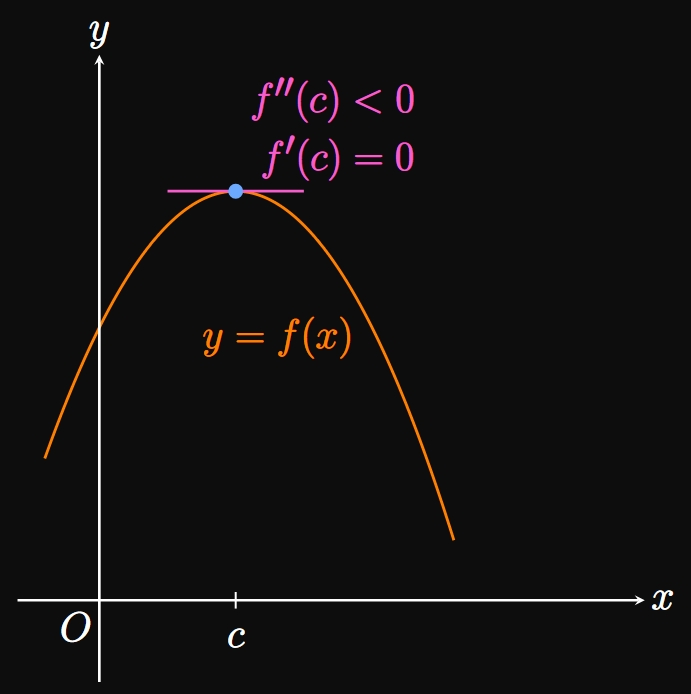

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \lt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(x = c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) = 0\) or \(f''(c)\) does not exist, then the test is inconclusive.

In part (a), because \(f''(c) \gt 0,\) \(f\) is concave up at \(c.\) Accordingly, the graph of \(f\) must be above the tangent at \(c,\) so \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(c.\) (See Figure 14A.) Conversely, in part (b) \(f''(c) \lt 0,\) meaning \(f\) is concave down at \(c.\) So the graph of \(f\) lies below the tangent at \(c;\) accordingly, \(c\) must be a relative maximum of \(f,\) as in Figure 14B. Part (c) states that \(f\) can have either a relative minimum, relative maximum, or neither at the critical number \(c\) if \(f''(c)\) equals \(0\) or does not exist.

PROOF To prove part (a) of the Second-Derivative Test, we consider the behavior of \(f\) on either side of the critical number \(c.\) We assume that \(f''\) is positive on some neighborhood around \(c\)—say, on \((a, b),\) where \(a \lt c \lt b.\) We consider two subintervals: \((a, c)\) and \((c, b).\) In the first case, let \(x \in (a, c).\) By the Mean Value Theorem for \(f'\) on \([x, c],\) a number \(k\) exists in \((x, c)\) such that \[f'(c) - f'(x) = f''(k) (c - x) \pd\] But we assume \(f''\) is positive on \((a, b),\) and \(a \lt x \lt k \lt c,\) so \(f''(k) \gt 0.\) In addition, \((c - x)\) is positive, so we must have \[f'(c) - f'(x) \gt 0 \pd\] But \(c\) is a critical number, so \(f'(c) = 0.\) Accordingly, we attain \[-f'(x) \gt 0 \or f'(x) \lt 0 \pd\] Thus, \(f\) is decreasing on the left of \(c.\) Applying the same logic to the subinterval \((c, b),\) let \(x \in (c, b).\) Then the Mean Value Theorem for \(f'\) on \([c, x]\) guarantees a number \(k \in (c, x)\) such that \[f'(x) - f'(c) = f''(k) (x - c) \pd\] But \(c \lt k \lt x \lt b,\) so \(f''(k) \gt 0.\) Also, \((x - c) \gt 0,\) so \[f'(x) - f'(c) \gt 0 \pd\] With \(f'(c) = 0,\) we have \[f'(x) \gt 0 \cma\] meaning \(f\) is increasing on the right of \(c.\) By the First-Derivative Test, because \(f'\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(c,\) \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(c.\) Proving part (b) is nearly identical, requiring a beginning assumption of \(f'' \lt 0\) on \((a, b).\) To show that part (c) is true, it suffices to give examples showing different behaviors when \(f''(c) = 0.\) An example is \(f(x) = x^3\) and \(g(x) = x^4,\) which both are twice-differentiable and have a critical number of \(0.\) Although \(f''(0) = 0\) and \(g''(0) = 0,\) \(f\) has no relative extremum at \(0,\) whereas \(g\) has a relative minimum at \(0.\) Therefore, no consistent conclusion exists if \(f''(c) = 0.\) \[\qedproof\]

Increasing and Decreasing The function \(f',\) the first derivative of \(f,\) signifies whether \(f\) is increasing or decreasing over an interval.

- If \(f' \gt 0\) on an interval, then \(f\) is increasing on that interval.

- If \(f' \lt 0\) on an interval, then \(f\) is decreasing on that interval.

First-Derivative Test The First-Derivative Test enables us to determine whether a function has a relative maximum, a relative minimum, or neither at a critical number. If \(c\) is a critical number of \(f,\) then

- \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has no relative extremum at \(c\) if \(f'\) does not change sign at \(c.\)

Concavity We use the second derivative \(f''\) to determine the concavity of the graph of \(f.\) The graph of \(f\) is concave up over an interval if the graph lies above its tangents on that interval. Conversely, the graph is concave down if the graph lies below its tangents.

- If \(f''(x) \gt 0\) for all \(x\) in an interval, then the graph of \(f\) is concave up on that interval.

- If \(f''(x) \lt 0\) for all \(x\) in an interval, then the graph of \(f\) is concave down on that interval.

The function \(f\) has an inflection point at \(x = a\) if the graph of \(f\) switches concavity at \(x = a.\)

Second-Derivative Test The Second-Derivative Test enables us to classify critical points of \(f\) as corresponding to relative minima or relative maxima. It is an alternative to the First-Derivative Test.

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \gt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(x = c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \lt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(x = c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) = 0\) or \(f''(c)\) does not exist, then the test is inconclusive.