2.6: Differentiating Logarithmic Functions

In Section 2.5 we used Implicit Differentiation to attain the derivatives of all six inverse trigonometric functions. In this section we build on this idea by investigating the derivatives of logarithmic functions, as well as their applications. In this section we discuss the following topics:

Derivatives of Logarithmic Functions

In Section 2.2 we defined the number \(e \approx 2.718\) such that \(\textderiv{}{x}(e^x) = e^x.\) The inverse function of the exponential function is the logarithmic function. That is, if \(g(x) = b^x,\) where \(b\) is positive and \(b \ne 1,\) then \(\inv g(x)\) \(= \log_b x.\) The inverse function of \(e^x\) is called the natural logarithm (abbreviated by the symbol \(\ln\)), a logarithm whose base is the number \(e.\) That is, \[g(x) = e^x \iffArrow \inv g(x) = \ln x \pd\]

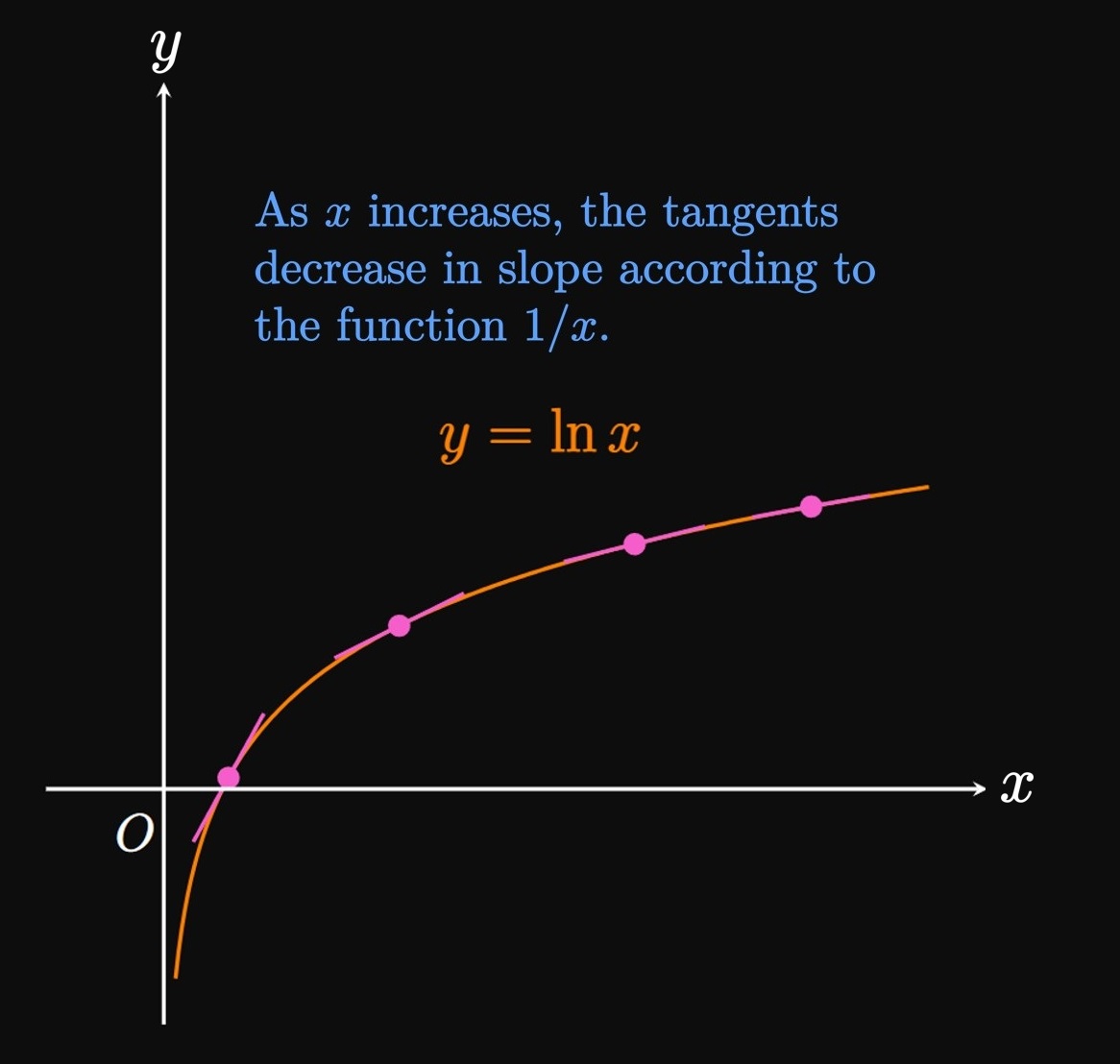

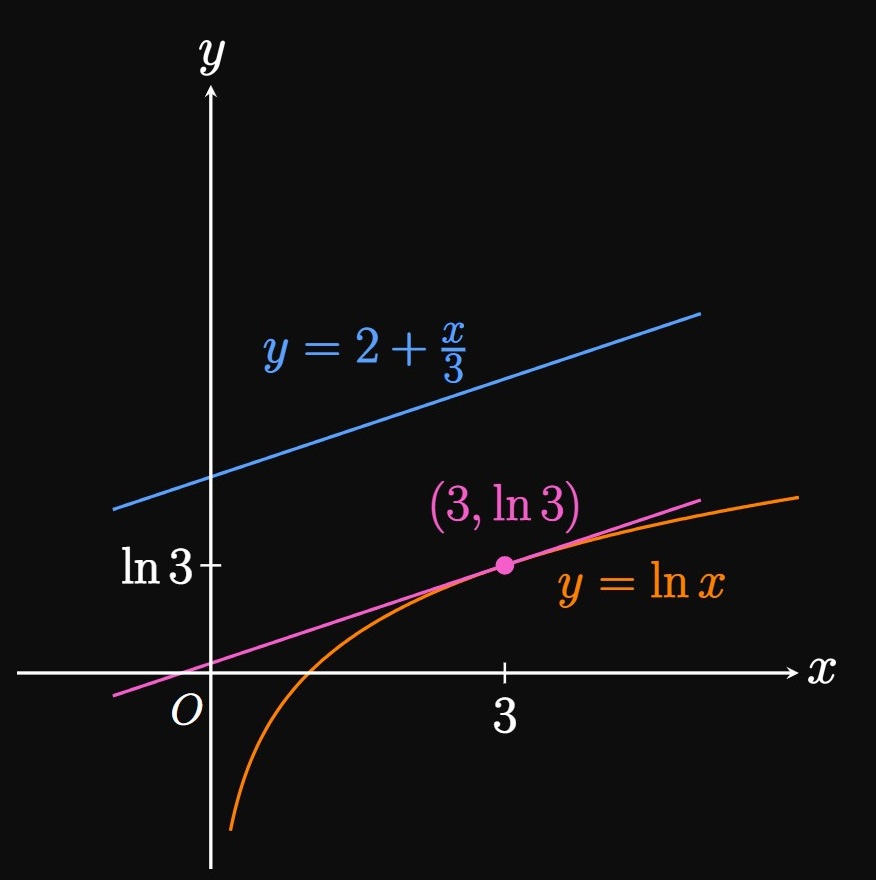

Letting \(y = \ln x,\) it follows that \(x = e^y.\) Performing Implicit Differentiation, we get \[ 1 = e^y \deriv{y}{x} \so \deriv{y}{x} = \frac{1}{e^y} \pd \] But since \(x = e^y,\) we have \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} \par{\ln x} = \frac{1}{x} \pd \label{eq:deriv-ln-x} \end{equation} It is astonishing that the rate of change of the natural logarithm, defined using the irrational number \(e \approx 2.718,\) turns out to be such a clean result—the reciprocal function. \(\eqrefer{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) is extremely useful and is central to many operations we will perform in future chapters. This result is intuitive because \(y = \ln x\) slows in growth as \(x\) increases; \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) corroborates this observation by asserting that the curve's tangents decrease to \(0\) as \(x \to \infty\) (Figure 1). Paradoxically, although its tangents decrease to \(0\) as \(x\) grows, the function \(\ln x\) grows to infinity as \(x\) approaches infinity—that is, \(\lim_{x \to \infty} \ln x = \infty.\)

Differentiating Logarithms of Any Base \(\eqrefer{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) gives the derivative of a logarithmic function whose base is \(e.\) But if the base is any positive number \(b \ne 1,\) then the Change of Base Formula for Logarithms (from Section 0.9) gives \[\log_b x = \frac{\ln x}{\ln b} \pd\] Since \(b\) is a constant, \(\ln b\) is a constant. Thus, \[\deriv{}{x} \par{\log_b x} = \frac{1}{\ln b} \cdot \deriv{}{x} \par{\ln x} \pd\] Then using \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) gives \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} \par{\log_b x} = \frac{1}{x \ln b} \pd \label{eq:deriv-log-b} \end{equation} Observe that \(\eqref{eq:deriv-log-b}\) agrees with \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) because \(\ln b = 1\) if \(b = e.\) This explains why we use the number \(e\) in calculus—so that the derivatives of \(e^x\) and \(\ln x\) are convenient to use.

The result of Example 4 is an extension of \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln-x}\) and should be remembered: \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} (\ln \abs x) = \frac{1}{x} \pd \label{eq:deriv-ln|x|} \end{equation} In Chapter 4 we'll need the natural logarithm to be defined for all nonzero values, so \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln|x|}\) will be important.

Logarithmic Differentiation

To differentiate an expression that contains many powers, products, and quotients, it's often tedious to use just the differentiation rules we have learned so far. But logarithms transform products and quotients into sums and differences, and they convert powers into multiples. Thus, Logarithmic Differentiation is an easier method for differentiating combinations of powers, multiples, and quotients. Let's refresh ourselves on logarithm laws, shown below.

- \(\ln(ab) = \ln a + \ln b.\)

- \(\ds \ln \par{\frac{a}{b}} = \ln a - \ln b.\)

- \(\ln \par{a^p} = p \ln a.\)

- Take the natural logarithm of both sides to get \begin{equation} \label{eq:step-1} \ln y = \ln[f(x)] \pd \end{equation} Use logarithm laws to expand \(\ln[f(x)]\) into a sum or difference of logarithms. If \(f(x) \lt 0\) for some values of \(x,\) then write \(\ln \abs y = \ln \abs{f(x)}\) and use \(\eqref{eq:deriv-ln|x|}.\)

- Differentiate both sides of \(\eqrefer{eq:step-1}\) implicitly; the resulting left-hand expression is \((1/y) \, \textderiv{y}{x}.\)

- Solve for \(\textDeriv{y}{x}\) by multiplying both sides by \(y = f(x).\)

Both the base and power are variable, so we cannot use the Power Rule. Instead, there are two viable options—using Logarithmic Differentiation or converting the base to be \(e.\)

Method 1

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides of \(y = x^{\sqrt[3] x}\) gives

\[

\ba

\ln y &= \ln \par{x^{\sqrt[3] x}} \nl

&= \sqrt[3] x \, \ln x \nl

&= x^{1/3} \ln x \pd

\ea

\]

Performing Implicit Differentiation, we have

\[

\ba

\frac{1}{y} \deriv{y}{x} &= \par{\tfrac{1}{3} x^{-2/3}} \ln x + x^{1/3} \par{\frac{1}{x}} \nl

&= \frac{\ln x}{3 x^{2/3}} + \frac{1}{x^{2/3}} \nl

&= \frac{\ln x + 3}{3 x^{2/3}} \pd

\ea

\]

Solving for \(\textderiv{y}{x}\)

(and remembering

Method 2 Note that \[x^{\sqrt[3] x} = \par{e^{\ln x}}^{\sqrt[3] x} = e^{\sqrt[3] x \, \ln x} \pd\] By the Chain Rule, \[ \ba \deriv{}{x} \par{e^{\sqrt[3] x \, \ln x}} &= e^{\sqrt[3] x \, \ln x} \deriv{}{x} \par{\sqrt[3] x \, \ln x} \nl &= e^{\sqrt[3] x \, \ln x} \par{\frac{\ln x + 3}{3 x^{2/3}}} \nl &= \boxed{x^{\sqrt[3] x} \par{\frac{\ln x + 3}{3 x^{2/3}}}} \ea \]

The Number \(e\) as a Limit

Since \(e\) is prevalent in calculus, we often need to recognize limits as disguised versions of \(e.\) If \(f(x) = \ln x,\) then \(f'(x) = 1/x\) and so \(f'(1) = 1.\) From the limit definition of a derivative, we get \[ \ba f'(1) &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(1 + h) - f(1)}{h} \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\ln(1 + h) - \ln 1}{h} \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{1}{h} \ln (1 + h) \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} \ln(1 + h)^{1/h} \pd \ea \] Since \(f'(1) = 1,\) we have \[1 = \lim_{h \to 0} \ln(1 + h)^{1/h} \pd\] Raising \(e\) to the power of each side, and noting that the exponential function is continuous, we see \begin{align} e^1 &= e^{\lim_{h \to 0} \ln(1 + h)^{1/h}} \nonum \nl e &= \lim_{h \to 0} e^{\ln (1 + h)^{1/h}} \nonum \nl e &= \lim_{h \to 0} (1 + h)^{1/h} \pd \label{eq:e-lim-x} \end{align}

Exponential Function Raising both sides of \(\eqref{eq:e-lim-x}\) to the power of \(x\) shows \[ \ba e^x &= \parbr{\lim_{h \to 0} (1 + h)^{1/h}}^x \nl &= \lim_{h \to 0} (1 + h)^{x/h} \pd \ea \] By letting \(n = x/h,\) we note that \(n \to \infty\) as \(h \to 0^+.\) Because \(h = x/n,\) the limit becomes \begin{equation} e^x = \lim_{n \to \infty} \par{1 + \frac{x}{n}}^n \pd \label{eq:exp-lim} \end{equation} Taking \(x = 1\) gives another limit representation of \(e \col\) \begin{equation} e = \lim_{n \to \infty} \par{1 + \frac{1}{n}}^n \pd \label{eq:e-lim} \end{equation} This limit is famous, and in Chapter 8 we will investigate this limit's presence in compound interest.

Derivatives of Logarithmic Functions The natural logarithm is the inverse function of \(e^x.\) We denote the natural logarithm as \(\ln x,\) whose base is \(e\) and derivative is \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} \par{\ln x} = \frac{1}{x} \pd \eqlabel{eq:deriv-ln-x} \end{equation} If \(b\) is a positive constant and \(b \ne 1,\) then \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} \par{\log_b x} = \frac{1}{x \ln b} \pd \eqlabel{eq:deriv-log-b} \end{equation} The following derivative is also noteworthy: \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} (\ln \abs x) = \frac{1}{x} \pd \eqlabel{eq:deriv-ln|x|} \end{equation}

Logarithmic Differentiation Logarithmic Differentiation is an application of Implicit Differentiation that allows for simpler differentiation of products, quotients, and powers of functions. If \(y = f(x),\) then to find \(\textDeriv{y}{x}\) using Logarithmic Differentiation, use the following steps.

- Take the natural logarithm of both sides to get \begin{equation} \ln y = \ln[f(x)] \pd \eqlabel{eq:step-1} \end{equation} Use logarithm laws to expand \(\ln[f(x)]\) into a sum or difference of logarithms.

- Differentiate both sides of \(\eqrefer{eq:step-1}\) implicitly; the resulting left-hand expression is \((1/y) \, \textderiv{y}{x}.\)

- Solve for \(\textDeriv{y}{x}\) by multiplying both sides by \(y = f(x).\)

The Number \(e\) as a Limit The exponential function is given by the limit \begin{equation} e^x = \lim_{n \to \infty} \par{1 + \frac{x}{n}}^n \pd \eqlabel{eq:exp-lim} \end{equation} The number \(e\) has the following limit representation: \begin{equation} e = \lim_{n \to \infty} \par{1 + \frac{1}{n}}^n \pd \eqlabel{eq:e-lim} \end{equation}