10.3: Integral Test

In Section 10.2 we calculated the exact values of geometric series and telescoping series. But most other types of infinite series are impossible to evaluate exactly. Instead, we interest ourselves in whether a series converges or diverges using a toolbox of convergence tests. If a series converges, then we know it is appropriate to estimate its exact value using a partial sum. (Conversely, we know to avoid approximating a series if it diverges.) In this section we introduce one such convergence test, in which we connect infinite series to improper integrals. We discuss the following topics:

Integral Test

In Section 6.5 we evaluated improper integrals and concluded whether they converged or diverged. It turns out that infinite series behave similarly to improper integrals under a set of conditions. Consider the infinite series \(S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n,\) and let \(f\) be a real-valued function such that \(f(n) = a_n.\) Suppose that \(f\) is continuous, positive, and decreasing. Then the Integral Test asserts that the convergence or divergence of \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) matches the convergence or divergence of \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x.\) Simply put, if the test's conditions are met, then we evaluate \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) to see whether it converges or diverges—and make the same conclusion about \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n.\)

- If \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) converges, then \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) also converges.

- If \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) also diverges.

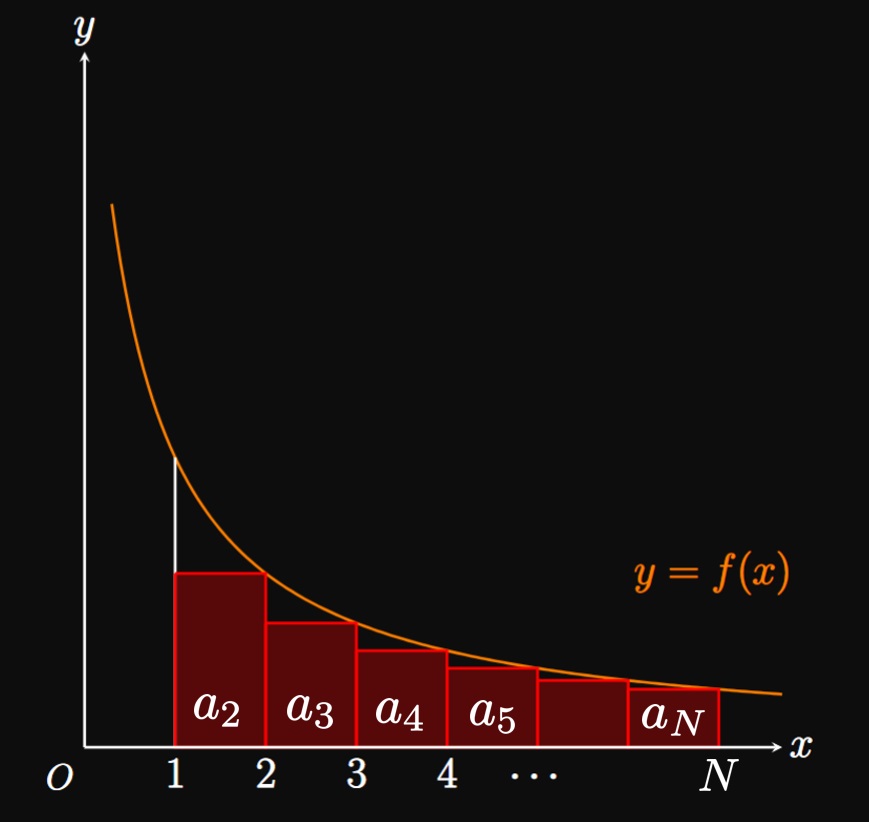

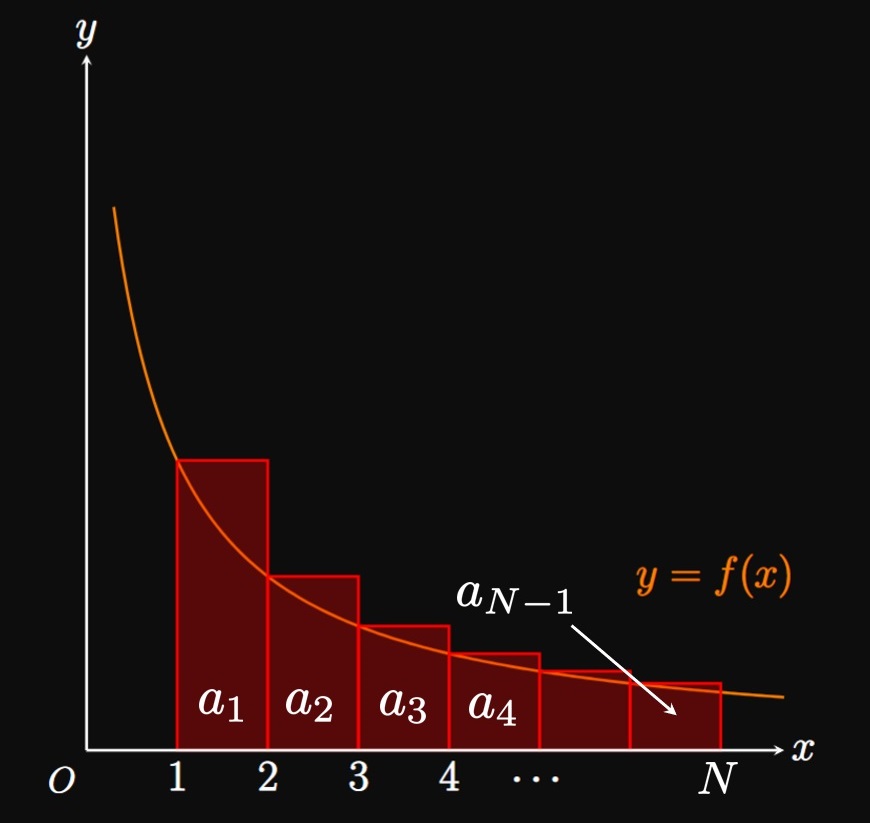

PROOF Let \(S_N = \sum_{i = 1}^N a_i.\) A right Riemann sum with \(\Delta x = 1\) approximates the area under \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = 1\) to \(x = N\) to be \[ \ba \sum_{i = 2}^N a_i &= \Delta x[f(2) + f(3) + f(4) + \cdots + f(N)] \nl &= 1[a_2 + a_3 + a_4 + \cdots + a_N] \pd \ea \] Since \(f\) is positive and decreasing, \(\sum_{i = 2}^N a_i\) is an underestimate of the area. (See Figure 1A.) Thus, we have \[ \ba \sum_{i = 2}^N a_i &\leq \int_1^N f(x) \di x \nl a_1 + \sum_{i = 2}^N a_i &\leq a_1 + \int_1^N f(x) \di x \pd \ea \] Suppose that \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) converges and that \(a_1 + \int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) equals some number \(K.\) Then we see \[ S_N = a_1 + \sum_{i = 2}^N a_i \leq a_1 + \int_1^N f(x) \di x \leq a_1 + \int_1^\infty f(x) \di x = K \cma \] so the sequence \(\{S_N\}\) is bounded above. Also, observe that \[S_{N + 1} = S_N + a_{N + 1} \geq S_N\] because \(a_{N + 1} = f(N + 1)\) \(\geq 0.\) Thus, \(\{S_N\}\) is an increasing, bounded sequence. By the Monotonic Sequence Theorem (from Section 10.1), \(\{S_N\}\) is convergent and so \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) is convergent. Now assume that \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges. Using a left Riemann sum estimates the region's area to be \[ \ba \sum_{i = 1}^{N - 1} a_i &= \Delta x [f(1) + f(2) + f(3) + \cdots + f(N - 1)] \nl &= 1[a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + \cdots + a_{N - 1}] \pd \ea \] This approximation overestimates the area, so we have \[\sum_{i = 1}^{N - 1} a_i \geq \int_1^N f(x) \di x \pd\] (See Figure 1B.) The partial sum then becomes \[S_N = \sum_{i = 1}^{N - 1} a_i + a_N \geq a_N + \int_1^N f(x) \di x \pd\] Since \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges, and since \(f(x) \geq 0,\) we have \(\int_1^N f(x) \di x\) \(\to \infty\) as \(N \to \infty.\) Consequently, \(S_N \to \infty\) as \(N \to \infty\) as well, meaning \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) diverges. \[\qedproof\]

CAUTION In general, the value of \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) does not equal \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n.\) For example, in Example 1 note that \[\sum_{n = 0}^\infty \frac{1}{n^2 + 1} \ne \int_0^\infty \frac{1}{x^2 + 1} \di x = \frac{\pi}{2} \pd\] Instead, we interest ourselves solely in whether the improper integral converges or diverges. The conclusion, not the value, of the improper integral applies to the infinite series.

REMARK It is not necessary for \(f\) always to be positive and decreasing. Instead, \(f\) must eventually be positive and decreasing—namely, for some \(x \geq N.\) Through this condition, the Integral Test establishes the convergence or divergence of \(\sum_{n = N}^\infty a_n,\) which matches the convergence or divergence of \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n.\) (The partial sum \(\sum_{i = 1}^{N - 1} a_i\) is finite and so does not influence convergence or divergence.) The following example demonstrates this idea.

\(p\)-Series

The family of series \[S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^p}\] converges or diverges depending on the value of \(p.\) If \(p \lt 0,\) then \(1/n^p \to \infty\) as \(n \to \infty\) and so the series diverges by the Divergence Test. But for \(p \gt 0,\) the function \(1/x^p\) is continuous, positive, and decreasing for \(x \geq 1.\) We therefore compare the series to the improper integral \[\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x^p} \di x \cma\] which diverges for \(p \leq 1\) and converges for \(p \gt 1\) (as we proved in Section 6.5). Hence, the Integral Test asserts that \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \par{1/n^p}\) also converges for \(p \gt 1\) and diverges for \(p \leq 1.\) This proof justifies why the Harmonic series (from Section 10.2), given by \[\sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \cdots \cma\] is divergent—it is a \(p\)-series with \(p = 1.\)

- \(\ds \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^4}\)

- \(\ds \sum_{n = 2}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{n^3}}\)

- \(\ds \sum_{n = 5}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt[3] n}\)

- This series has \(p = 4 \gt 1,\) so it converges.

- Observe that \[\sum_{n = 2}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{n^3}} = \sum_{n = 2}^\infty \frac{1}{n^{3/2}} \pd\] Since \(p = 3/2 \gt 1,\) the series converges.

- We see \[\sum_{n = 5}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt[3] n} = \sum_{n = 5}^\infty \frac{1}{n^{1/3}} \pd\] Identifying \(p = 1/3 \leq 1,\) we conclude that the series diverges.

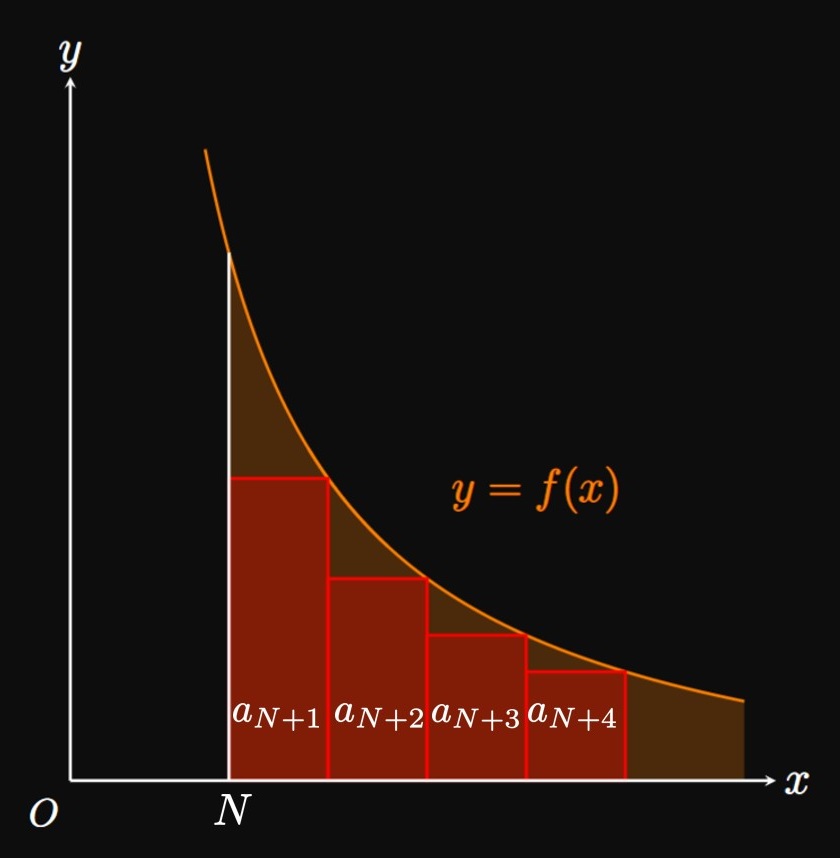

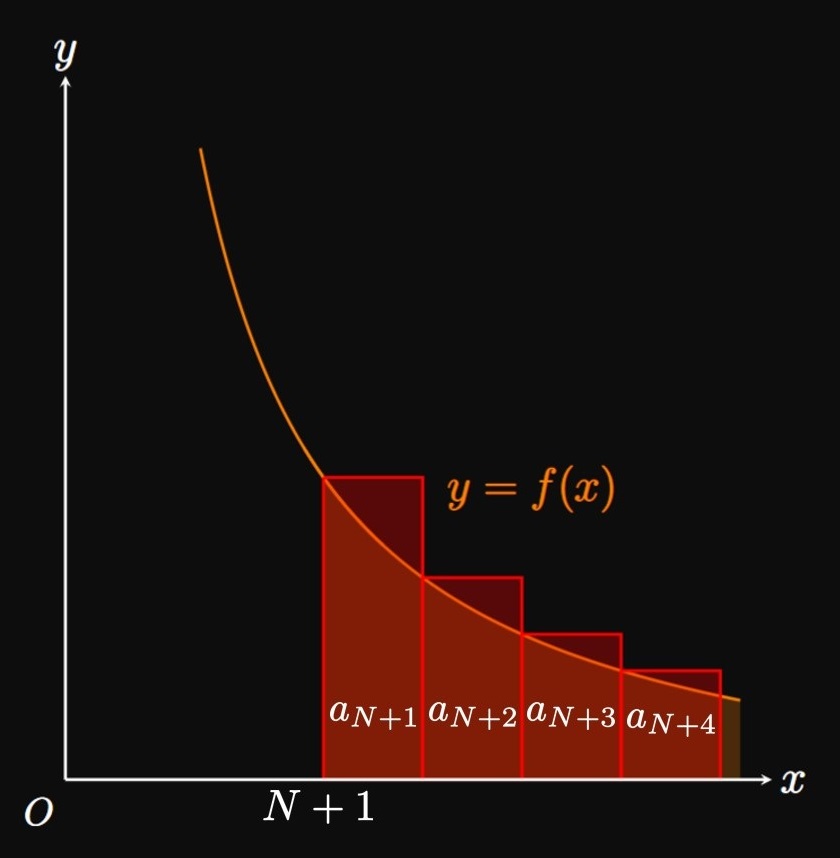

Error Bounds with the Integral Test

Most infinite series cannot be evaluated directly. Instead, we estimate their values using partial sums; that is, we approximate \(S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) to be the sum of the first \(N\) terms, \(S_N = \sum_{i = 1}^N a_i.\) The error \(R_N\) in the approximation is the numerical difference between the true sum \(S\) and the partial sum \(S_N\)—mathematically, \(S_N + R_N = S.\) By expanding terms, we see \[ \ba R_N &= S - S_N \nl &= \sum_{n = N + 1}^\infty a_n = a_{N + 1} + a_{N + 2} + a_{N + 3} + \cdots \pd \ea \] Think of \(R_N\) as the sum of the remaining terms, which we exclude from the approximation \(S_N.\) The sum \(R_N\) is therefore a right Riemann sum for the region under \(y = f(x)\) between \(x = N\) and \(x = \infty\) (Figure 2A), and it is a left Riemann sum for the region between \(x = N + 1\) and \(x = \infty\) (Figure 2B). By comparing areas, it is apparent that \begin{equation} \int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x \leq R_N \leq \int_N^\infty f(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:R-bound} \end{equation} Accordingly, our approximation \(S_N = \sum_{i = 1}^N a_i\) differs from the true value of \(S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) by no more than \(\int_N^\infty f(x) \di x,\) and by no less than \(\int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x.\) Since \(R_N = S - S_N,\) \(\eqrefer{eq:R-bound}\) becomes \[ \int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x \leq S - S_N \leq \int_N^\infty f(x) \di x \pd \] Adding \(S_N\) to every term gives \begin{equation} S_N + \int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x \leq S \leq S_N + \int_N^\infty f(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:S-bound} \end{equation} This equation enables us to bound the true value of the sum \(S,\) that is, construct an interval in which \(S\) must reside.

Integral Test Let \(f\) be a function that satisfies \(f(n) = a_n.\) Suppose that \(f(x)\) is continuous, positive, and decreasing for all \(x \geq 1.\)

- If \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) converges, then \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) also converges.

- If \(\int_1^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) also diverges.

But a few nuances exist for the test: The Integral Test works for any starting index, not just \(n = 1.\) When we apply the test, we need \(f\) to ultimately be positive and decreasing.

\(p\)-Series The family of sums \[S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^p} \cma\] called a \(\bf p\)-series, converges for \(p \gt 1\) and diverges for \(p \leq 1.\)

Error Bounds with the Integral Test When we approximate \(S = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty a_n\) using the partial sum \(S_N = \sum_{i = 1}^N a_i,\) the error in the estimate is \(R_N.\) Let \(f\) be a continuous, positive, and decreasing function on \([N, \infty)\) such that \(f(n) = a_n.\) The Integral Test enables us to construct an error bound for \(R_N\) as follows: \begin{equation} \int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x \leq R_N \leq \int_N^\infty f(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:R-bound} \end{equation} Then we bound \(S\) using \begin{equation} S_N + \int_{N + 1}^\infty f(x) \di x \leq S \leq S_N + \int_N^\infty f(x) \di x \pd \eqlabel{eq:S-bound} \end{equation}