1.5: Formal Definition of a Limit

In Section 1.1 we introduced a working definition of a limit. Using this concept, we explored limit laws and calculated limits algebraically in Section 1.2. But we have yet to define limits formally, through mathematical notation. In this section we learn to build proofs of limit statements, through the following topics:

- Formal Definition of a Limit

- Formal Definitions of One-Sided Limits

- Formal Definitions of Infinite Limits

Formal Definition of a Limit

In Section 1.1

we defined the notation \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L\) as follows:

We can make \(f(x)\) arbitrarily close to \(L\)

by making \(x\) sufficiently close to \(a\)

(but not equal to error tolerance

—as

small as we wish.

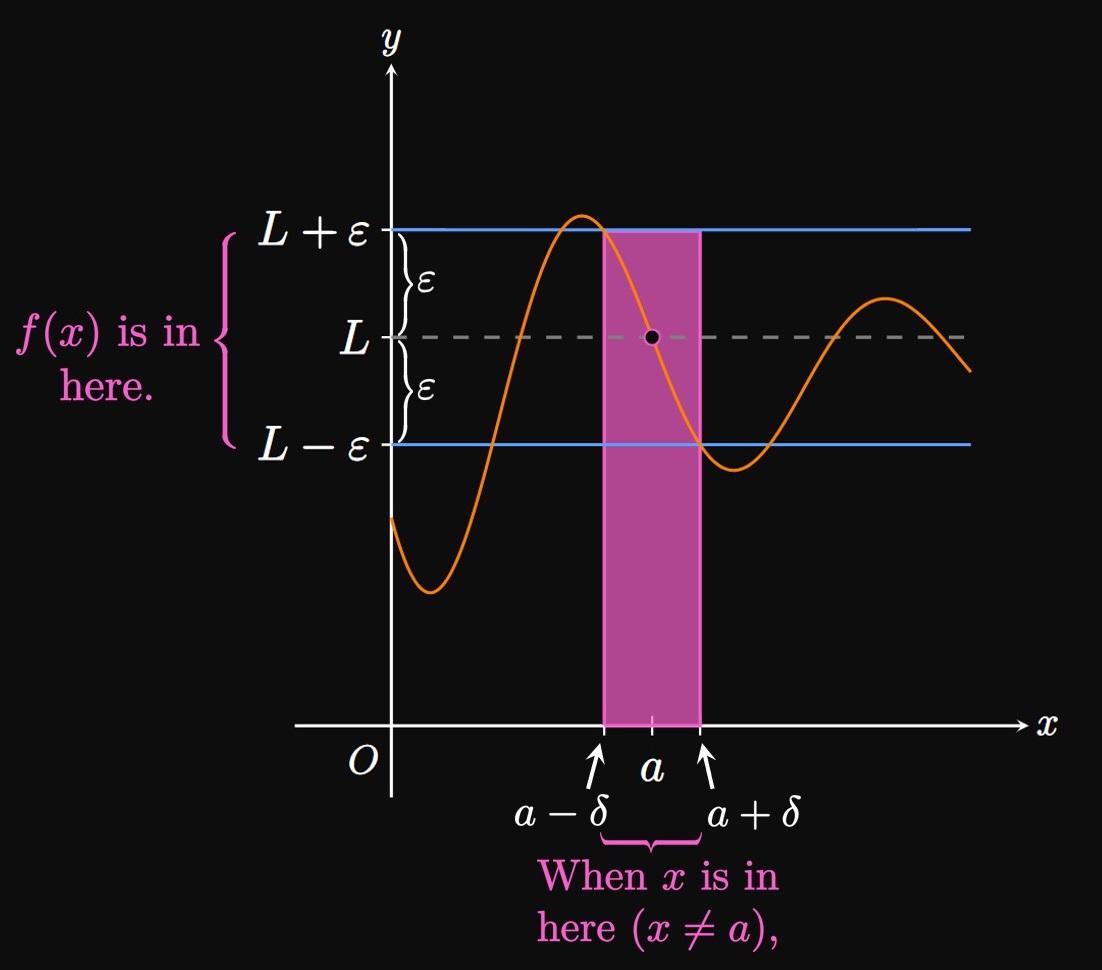

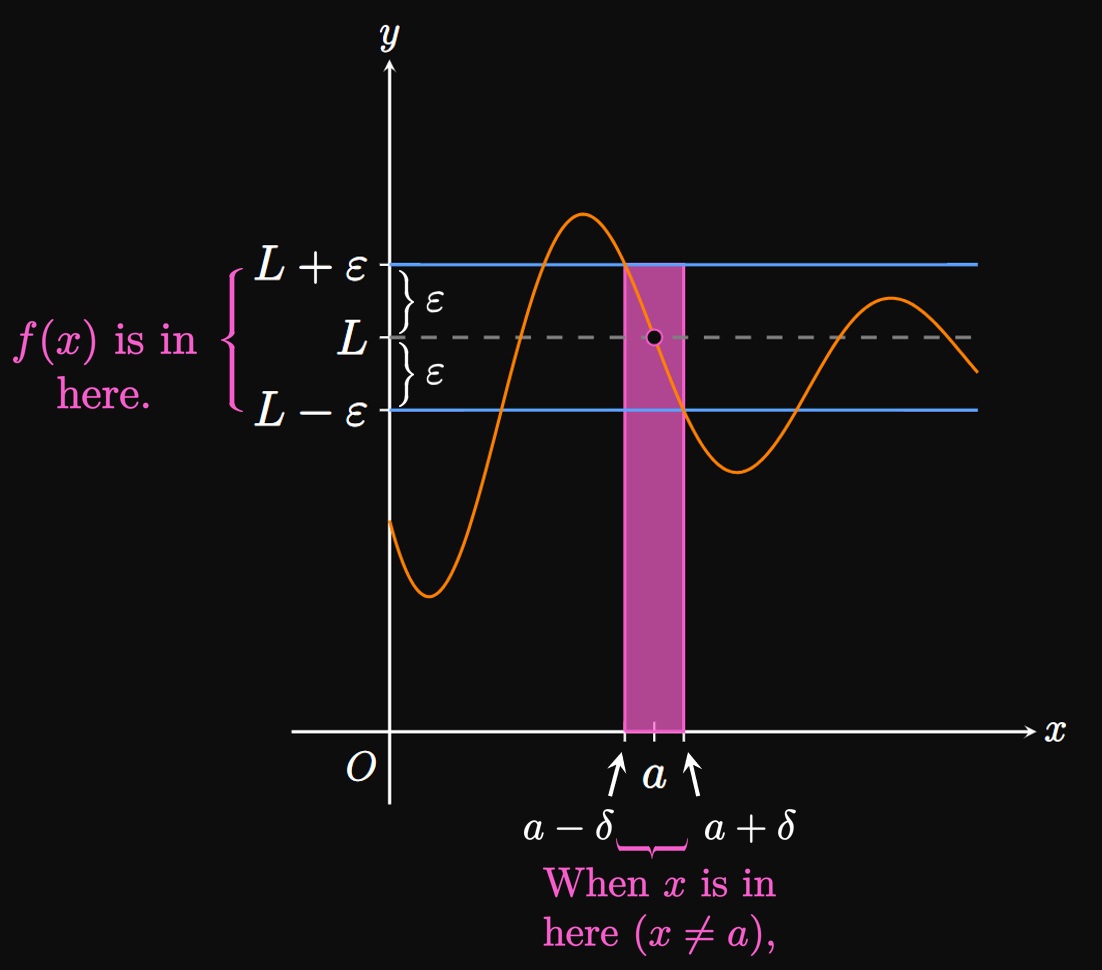

Comparing Figure 1A

to Figure 1B, we see that

if we choose a smaller \(\varepsilon,\) then we may need a smaller \(\delta.\)

In words, a smaller error tolerance requires us to make \(x\) closer to \(a\)

(without being equal to

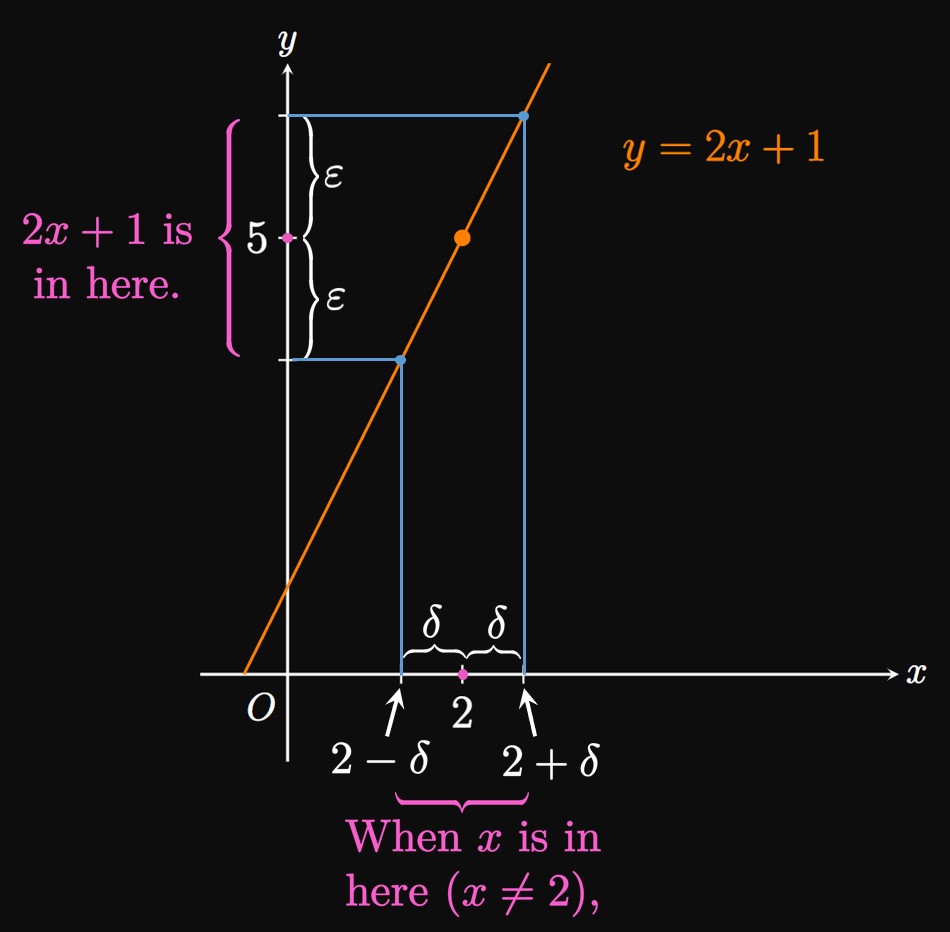

For example, the statement \(\lim_{x \to 2} (2x + 1) = 5\)

means, for any \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\)

exists such that

\begin{equation}

\abs{(2x + 1) - 5} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 2} \lt \delta \pd \label{eq:del-ep-ex}

\end{equation}

To prove this limit, our goal is to express \(\delta\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\)

Think of \(\varepsilon\) as the error tolerance—the number

such that \(2x + 1\) differs from \(5\) by less than \(\varepsilon.\)

In \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-ex}\) the first inequality becomes \(\abs{2x - 4} \lt \varepsilon,\)

or \(\abs{x - 2} \lt \varepsilon/2.\)

Comparing this inequality to \(\abs{x - 2} \lt \delta,\)

we choose \(\delta = \varepsilon/2.\)

Thus, \(\lim_{x \to 2} (2x + 1) = 5\) is true because

\[\abs{(2x + 1) - 5} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 2} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{2} \pd\]

In words, to ensure that \(2x + 1\) is within \(\varepsilon\)

of \(5,\) we must make \(x\) less than a distance \(\varepsilon/2\)

away from \(2.\)

(See Figure 2.)

In this form, we have the freedom to choose how close \(2x + 1\) is

to \(5\) by requiring a sufficiently small \(\varepsilon.\)

For example, if we want \(2x + 1\) to differ from \(5\) by less than \(\varepsilon = 0.05,\)

then we need

\[\abs{x - 2} \lt \frac{0.05}{2} = 0.025 \iffArrow 1.975 \lt x \lt 2.025 \pd\]

Likewise, if \(2x + 1\) is less than \(\varepsilon = 0.01\) away from \(5,\)

then we require

\[\abs{x - 2} \lt \frac{0.01}{2} = 0.005 \iffArrow 1.995 \lt x \lt 2.005 \pd\]

Observe that the interval of allowable \(x\) shrinks as we

demand a smaller error tolerance \(\varepsilon.\)

This pattern repeats: We have the liberty of making \(2x + 1\)

as close to \(5\) as we wish by selecting

an arbitrarily small value of \(\varepsilon\) and

demanding that \(x\) differ from \(2\) (with

- Define \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) to be given, and define \(\delta\) to be a positive number such that \begin{equation} \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:del-ep} \end{equation}

- In the inequality \(\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon,\) perform algebraic manipulation to isolate \(\abs{x - a}.\) Doing so gives a bound for \(\abs{x - a}\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\)

- Choose \(\delta\) to be the bound for \(\abs{x - a}\) you attained in Step 2.

- Repeat Step 2 to show that your choice of \(\delta\) ensures that \(\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon\) when \(0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta.\)

- Defining \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) Let \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) be given. Observe that \(f(x) = 3x + 4,\) \(L = 7,\) and \(a = 1.\) So, following the structure of \(\eqref{eq:del-ep},\) we want to find a number \(\delta \gt 0\) such that \begin{equation} \abs{(3x + 4) - 7} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 1} \lt \delta \pd \label{eq:del-ep-line-ex} \end{equation}

- Bounding \(\abs{x - 1}\) Manipulating the first inequality in \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-line-ex},\) we isolate the factor \(\abs{x - 1}\) as follows: \[\abs{3x - 3} \lt \varepsilon \iffArrow 3 \abs{x - 1} \lt \varepsilon \iffArrow \abs{x - 1} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{3} \pd\]

- Selecting \(\delta\) Now we guess a value of \(\delta\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\) We obtained the bound \(\abs{x - 1} \lt \varepsilon/3.\) Comparing this inequality to \(\abs{x - 1} \lt \delta,\) we choose \(\delta = \varepsilon/3.\)

- Constructing the Proof We now prove that \(\delta = \varepsilon/3\) satisfies \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-line-ex}.\) For \(\abs{x - 1} \lt \delta,\) we see \[\abs{(3x + 4) - 7} = \abs{3x - 3} = 3 \abs{x - 1} \lt 3 \delta = 3 \par{\frac{\varepsilon}{3}} = \varepsilon \pd\] Hence, \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-line-ex}\) becomes \[ \abs{(3x + 4) - 7} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 1} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{3} \pd \] Thus, \(\lim_{x \to 1} (3x + 4) = 7\) is proven. In words, if we want \(3x + 4\) to differ from \(7\) by less than any positive number \(\varepsilon,\) then we must make \(x\) be within \(\varepsilon/3\) of \(1.\)

In proving a limit, we first guess an appropriate \(\delta\) and then show that the choice of \(\delta\) satisfies \(\eqref{eq:del-ep}.\) Doing so, we write the proof after we use algebra to decide a suitable \(\delta.\) In mathematics, it is generally easy to check whether a solution is valid—the difficult part is first obtaining the solution. Thus, through clever algebraic tricks, mathematicians often work backward to prove a result.

- Defining \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) Let \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) be given. With \(f(x) = \sqrt x,\) \(a = 4,\) and \(L = 2,\) we follow the structure of \(\eqref{eq:del-ep}\) by finding a number \(\delta \gt 0\) such that \begin{equation} \abs{\sqrt x - 2} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt \delta \pd \label{eq:del-ep-sqrt-ex} \end{equation}

- Bounding \(\abs{x - 4}\) In the first inequality in \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-sqrt-ex},\) we multiply by the conjugate \(\sqrt x + 2\) to expose the factor \(\abs{x - 4}.\) Doing so, we see \[\abs{\sqrt x - 2} = \abs{\par{\sqrt x - 2} \cdot \frac{\sqrt x + 2}{\sqrt x + 2}} = \abs{\frac{x - 4}{\sqrt x + 2}} \lt \varepsilon \pd\] At this stage, it is difficult to bound \(\abs{x - 4}\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\) To simplify this problem, let's compromise by using a larger bound for \(\abs{x - 4} \col\) We observe that \(1/\par{\sqrt x + 2}\) \(\leq 1/2.\) So \[\abs{\frac{x - 4}{\sqrt x + 2}} \leq \abs{\frac{x - 4}{2}} \implies \abs{\frac{x - 4}{2}} \lt \varepsilon \pd\] Thus, \(\abs{x - 4} \lt 2 \varepsilon.\)

- Selecting \(\delta\) We attained the bound \(\abs{x - 4} \lt 2 \varepsilon.\) Comparing this inequality to \(\abs{x - 4} \lt \delta,\) we choose \(\delta = 2 \varepsilon.\)

- Constructing the Proof We now verify that \(\delta = 2 \varepsilon\) satisfies \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-sqrt-ex}.\) For \(0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt \delta,\) we see \[\abs{\sqrt x - 2} = \abs{\frac{x - 4}{\sqrt x + 2}} \leq \abs{\frac{x - 4}{2}} \lt \frac{\delta}{2} = \frac{2 \varepsilon}{2} = \varepsilon \pd\] So \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-sqrt-ex}\) becomes \[ \abs{\sqrt x - 2} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt 2 \varepsilon \pd \] Thus, \(\lim_{x \to 4} \sqrt x = 2\) is proven. Accordingly, to make \(\sqrt x\) differ from \(2\) by less than \(\varepsilon,\) we must make \(x\) be within \(2\varepsilon\) of \(4.\)

It may be difficult to prove a limit \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L\) by finding a suitable choice of \(\delta.\) When this occurs, we must compromise. For example, we can determine an appropriate choice of \(\delta\) by considering a simpler problem—for example, by bounding \(\abs{x - a}\) using a larger number, as in Example 2.

- Defining \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) Let \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) be given. With \(f(x) = x^2,\) \(a = 4,\) and \(L = 16,\) we follow the structure of \(\eqref{eq:del-ep}\) by finding a number \(\delta \gt 0\) such that \begin{equation} \abs{x^2 - 16} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt \delta \pd \label{eq:del-ep-2-ex} \end{equation}

- Bounding \(\abs{x - 4}\) In \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-2-ex},\) we factor the quadratic to get \[\abs{x + 4} \abs{x - 4} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt \delta \pd\] But how do we bound \(\abs{x - 4}\) in the first inequality? We want to bound the product by finding any positive number \(C\) such that \(\abs{x + 4} \lt C.\) Then we see \[ \abs{x + 4} \abs{x - 4} \lt C \abs{x - 4} \lt \varepsilon \implies \abs{x - 4} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{C} \pd \] Since we are only interested in values of \(x\) close to \(4,\) it is safe to say \(\abs{x - 4} \lt 1.\) Then \(3 \lt x \lt 5\) and so \(7 \lt x + 4\lt 9,\) meaning it is appropriate to let \(C = 9.\) So \(\abs{x - 4} \lt \varepsilon/9.\)

- Selecting \(\delta\) We attained the bound \(\abs{x - 4} \lt \varepsilon/9.\) Comparing this inequality to \(\abs{x - 4} \lt \delta,\) we select \(\delta = \varepsilon/9.\) But now \(\abs{x - 4}\) must satisfy two inequalities: \[\abs{x - 4} \lt 1 \and \abs{x - 4} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{9} \pd\] To satisfy both restrictions, we choose \(\delta\) to be the smaller bound—namely, \[\delta = \min{1}{\frac{\varepsilon}{9}} \pd\]

-

Constructing the Proof

Using \(\delta = \varepsilon/9,\) we see

\[

\ba

\abs{x^2 - 16} &= \abs{x + 4} \abs{x - 4} \nl

&\lt \abs{x + 4} \, \delta \nl

&\lt 9 \delta \nl

&= 9 \par{\frac{\varepsilon}{9}} \nl

&= \varepsilon \pd

\ea

\]

Accordingly,

\[\abs{x^2 - 16} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 4} \lt \frac{\varepsilon}{9} \pd\]

Thus, \(\lim_{x \to 4} x^2 = 16.\)

But if \(\varepsilon \gt 9,\) then we enforce \(\abs{x - 4} \lt 1.\)

This proof is therefore valid for \(3 \lt x \lt 5\) (with

\(x \ne 4\)); for \(x\) outside this interval, we can increase the value of \(C\) as needed.

Formal Definitions of One-Sided Limits

In the Formal Definition of a Limit, \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L\) is true only if \(x\) differs from \(a\) by less than \(\delta \gt 0\) in either direction of \(a.\) Yet for a one-sided limit, we require \(x\) to differ from \(a\) by less than \(\delta\) in only one direction. We therefore attain the following formal definitions for one-sided limits.

- \(\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = L\) is true if and only if, for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if a - \delta \lt x \lt a \pd \label{eq:del-ep-left} \end{equation}

- \(\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = L\) is true if and only if, for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if a \lt x \lt a + \delta \pd \label{eq:del-ep-right} \end{equation}

- Defining \(\varepsilon\) and \(\delta\) Let \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) be given. We have \(a = 0,\) \(f(x) = \sqrt x,\) and \(L = 0.\) By \(\eqref{eq:del-ep-right},\) we want to find a number \(\delta \gt 0\) for which \[\abs{\sqrt x - 0} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt x \lt 0 + \delta \cma\] that is, \(\sqrt x \lt \varepsilon\) if \(0 \lt x \lt \delta.\)

- Bounding \(x\) Because \(\sqrt x \lt \varepsilon,\) \(x\) is nonnegative. Squaring both sides of the inequality yields \(x \lt \varepsilon^2.\)

- Selecting \(\delta\) Comparing the restriction \(0 \lt x \lt \varepsilon^2\) to the inequality \(0 \lt x \lt \delta,\) we choose \(\delta = \varepsilon^2.\)

-

Constructing the Proof

With \(\delta = \varepsilon^2,\) we see

\[\abs{\sqrt x - 0} = \sqrt x \lt \sqrt \delta = \sqrt{\varepsilon^2} = \varepsilon \]

(since

\(\varepsilon \gt 0\)) . Therefore, \[\abs{\sqrt x - 0} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt x \lt \varepsilon^2 \pd\] Accordingly, \(\lim_{x \to 0^+} \sqrt x = 0.\)

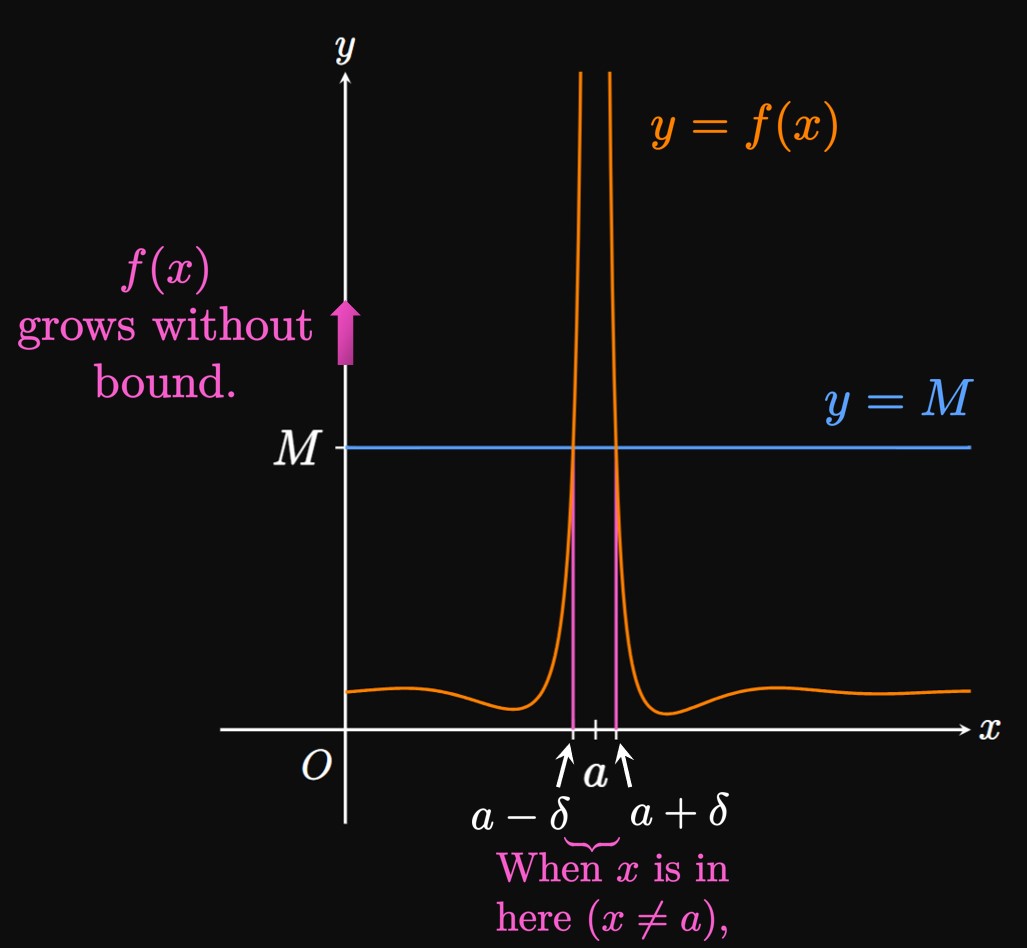

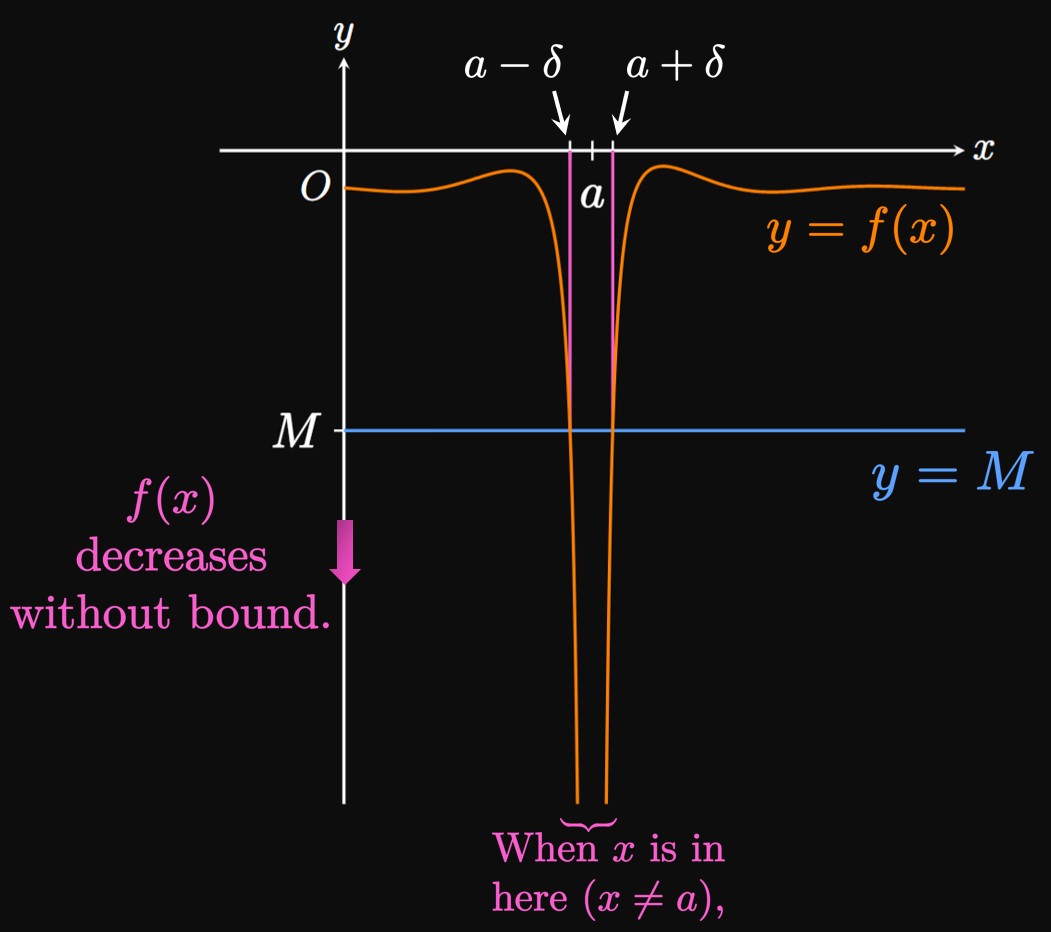

Formal Definitions of Infinite Limits

In Section 1.1

we stated that \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \infty\) means that

\(f(x)\) grows without bound as \(x\) is made close to \(a.\)

To provide a precise definition, we introduce a positive number \(M\)

that bounds \(f(x)\) from below.

Given any \(M \gt 0,\) there exists a \(\delta \gt 0\) such that

\begin{equation}

f(x) \gt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \label{eq:def-inf-lim}

\end{equation}

Geometrically, when \(x\) is in the interval \((a - \delta,\) \(a + \delta),\)

the curve \(f(x)\) is constantly above the line \(y = M.\)

Think of \(M\) as the floor

—we can select \(M\)

to be any number; the curve \(f\) will remain above \(y = M,\)

provided \(x\) differs from \(a\) by less than \(\delta\) (but

Similarly, the statement \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty\)

means that \(f\) decreases without bound as \(x\) is made closer to \(a\)

(but ceiling

; making \(M\) more negative may

require smaller values of \(\delta.\)

- \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if, for any positive number \(M,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} f(x) \gt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:def-inf-lim} \end{equation}

- \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty\) if and only if, for any negative number \(M,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} f(x) \lt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:def-inf-lim-neg} \end{equation}

- Defining \(M\) and \(\delta\) Note that \(a = k\) and \(f(x) = 1/(x - k)^2.\) Following \(\eqref{eq:def-inf-lim},\) we want to find a number \(\delta \gt 0\) such that, for any given \(M \gt 0,\) \[\frac{1}{(x - k)^2} \gt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - k} \lt \delta \pd\]

- Bounding \(\abs{x - k}\) In the first inequality, we reciprocate both sides to attain \[(x - k)^2 \lt \frac{1}{M} \pd\] (Reciprocating both sides of an inequality requires us to flip the inequality sign.) To bound the factor \(\abs{x - k},\) we take the square root of both sides to get \[\abs{x - k} \lt \sqrt{\frac{1}{M}} \pd\]

- Selecting \(\delta\) Comparing the inequality \(\abs{x - k} \lt \sqrt{1/M}\) to \(\abs{x - k} \lt \delta,\) we can choose \(\delta = \sqrt{1/M}.\)

- Constructing the Proof With \(\delta = \sqrt{1/M},\) we have \(\par{x - k}^2 \lt \delta^2\) and so \[\frac{1}{(x - k)^2} \gt \frac{1}{\delta^2} = \frac{1}{\par{\sqrt{1/M}}^2} = M \pd\] Thus, \[\frac{1}{(x - k)^2} \gt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - k} \lt \sqrt{\frac{1}{M}} \pd\] So \(\lim_{x \to k} \parbr{1/(x - k)^2} = \infty.\)

- Defining \(M\) and \(\delta\) We see \(a = 3\) and \(f(x) = -1/(6 - 2x)^2.\) By \(\eqref{eq:def-inf-lim-neg},\) we want to find a number \(\delta \gt 0\) such that, for any given \(M \lt 0,\) \[\frac{-1}{(6 - 2x)^2} \lt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 3} \lt \delta \pd\]

-

Bounding \(\abs{x - 3}\)

We manipulate the first inequality as follows:

\[

\ba

\frac{-1}{(6 - 2x)^2} \lt M

&\iffArrow

\frac{1}{(6 - 2x)^2} \gt -M \nl

&\iffArrow (6 - 2x)^2 \lt \frac{1}{-M} \nl

&\iffArrow (2x - 6)^2 \lt \frac{1}{-M} \pd

\ea

\]

To bound the factor \(\abs{x - 3},\) we take the square root of both sides

and then divide both sides by \(2.\)

Doing so shows

\[\abs{2x - 6} \lt \frac{1}{\sqrt{-M}} \iffArrow \abs{x - 3} \lt \frac{1}{2 \sqrt{-M}} \pd\]

(Remember that

\(M \lt 0.\)) - Selecting \(\delta\) Comparing the inequality \(\abs{x - 3} \lt 1/\par{2 \sqrt{-M}}\) to \(\abs{x - 3} \lt \delta,\) we can choose \(\delta = 1/\par{2 \sqrt{-M}}.\)

- Constructing the Proof With \(\delta = 1/\par{2 \sqrt{-M}}\) we see, for \(\abs{x - 3} \lt \delta,\) \[\frac{-1}{(6 - 2x)^2} = \frac{-1}{(2x - 6)^2} = \frac{-1}{4 (x - 3)^2} \lt \frac{-1}{4 \delta^2} = \frac{-1}{4 \par{\dfrac{1}{2 \sqrt{-M}}}^2} = M \pd\] Thus, \[\frac{-1}{(6 - 2x)^2} \lt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - 3} \lt \frac{1}{2 \sqrt{-M}} \pd\] So \(\lim_{x \to 3} \parbr{-1/(6 - 2x)^2} = -\infty.\)

Formal Definition of a Limit

The statement \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L\) means

for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that

\begin{equation}

\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:del-ep}

\end{equation}

It's intuitive to think of \(\varepsilon\) as an error tolerance

:

To ensure that \(f(x)\) differs from \(L\) by less than \(\varepsilon,\)

we require \(x\) to differ from \(a\) by less than \(\delta\)

(with

- Define \(\varepsilon \gt 0\) to be given, and define \(\delta\) to be a positive number such that \[ \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \]

- In the inequality \(\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon,\) perform algebraic manipulation to isolate \(\abs{x - a}.\) Doing so gives a bound for \(\abs{x - a}\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\)

- Choose \(\delta\) to be the bound for \(\abs{x - a}\) you attained in Step 2.

- Repeat Step 2 to show that your choice of \(\delta\) ensures that \(\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon\) when \(0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta.\)

Formal Definitions of One-Sided Limits We use special definitions for one-sided limits:

- \(\lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) = L\) means for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if a - \delta \lt x \lt a \pd \eqlabel{eq:del-ep-left} \end{equation}

- \(\lim_{x \to a^+} f(x) = L\) means for every \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} \abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \if a \lt x \lt a + \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:del-ep-right} \end{equation}

Formal Definitions of Infinite Limits To define infinite limits, we use the following definitions:

- \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \infty\) means for any positive number \(M,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} f(x) \gt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:def-inf-lim} \end{equation}

- \(\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -\infty\) means for any negative number \(M,\) a number \(\delta \gt 0\) exists such that \begin{equation} f(x) \lt M \if 0 \lt \abs{x - a} \lt \delta \pd \eqlabel{eq:def-inf-lim-neg} \end{equation}